- Author

- Nicholls, Bob

- Subjects

- Colonial navies, History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2003 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The first part of this article, which appeared in the December 2002 edition, reviewed American plans for the invasion of Auckland and Sydney. This part considers plans for Melbourne and Western Australia.

THE SURREPTITIOUS WORK ON PLANNING for attack on Australian ports was conducted in an overwhelming atmosphere of hospitality by the Great White Fleet’s hosts. This validated the advice given to President Teddy Roosevelt by Admiral Sims when the Australian invitation had been received.

He wrote that the men of the Fleet would ‘barely escape with their lives from the hospitality of the people.’ This certainly proved to be the case in Sydney.

Finally dragging itself away from this reception, the Fleet moved on to Melbourne – to receive the same treatment.

Nothing dissuaded the intrepid intelligence planning teams though, and they put the time spent in the Victorian State capital to good account.

The Melbourne Attack Plan

The team concluded that, if for some reason the occupation of Sydney was inappropriate, Port Phillip and Melbourne ‘. . . would be for many reasons a logical point of attack.’ As was the case with Sydney though, they stressed that command of the sea was a first requirement. No operations should take place against either port until command of the sea was sufficiently robust to enable a force of 25,000 soldiers to be moved across the Pacific. Also, as has already been mentioned, the Americans would first have to capture a port in New Zealand.

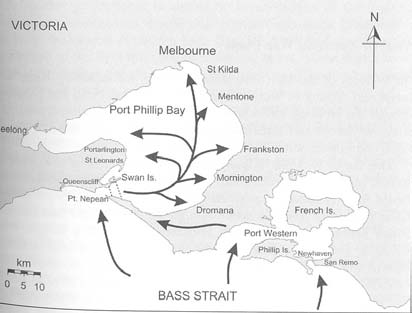

The entrance to Port Phillip presented problems. The entrance, at the Heads, followed a tortuous channel, with excellent sites for coastal defence batteries and good mining potential.

In the circumstances, a landing on the shores of Westernport (Port Western) seemed a good bet. If the entrance was mined (and there was a suspicion [erroneous] that it might be) then: ‘It would be best to land at San Remo and New Haven, and from there capture Phillip Island and thence clear up the road to Port Western, which would leave this road to the attack on the defences of Port Phillip open and also give a base from which to advance upon Melbourne.’

The team prepared a comprehensive survey of the various defences of the area, noting that ‘. . . after the attacking force of ships is [once] inside Port Phillip the fire of the forts at the entrance (The Heads) would be of little or no avail against it.’

The greatest weakness to the defence of Melbourne, the assessment concluded, was that ‘the entrance to Port Western is not defended.’

Before moving to the final area to be examined by the intelligence team’s studies it is worth remarking that, when the ships sailed from Melbourne they left nearly 200 sailors behind. Half were recovered.

Western Australia Attack Plans

The depleted and socially exhausted fleet made for the west of the continent before continuing their voyage round the world. As in the eastern States, plans were drawn up for attacking King George Sound, Albany, as well as Fremantle and Perth. Though the problem was relatively simple due to the almost complete absence of fortifications or personnel to man them, these reports were extensive and thorough, comprising 32 and 35 pages respectively.

One of the reasons the planners gave for attacking western ports was to deal with the situation where the United States might approach the eastern part of the continent from either the Indian Ocean or through the Dutch East Indies, in which case they would form a forward base similar to Auckland.

Conclusions

Each of the plans briefly mentioned above was quite extensive. They examined and recorded in detail all aspects of the location covered: rail networks and connections; shipping lines and frequency of sailings; shipyard facilities; coal availability; layout of the cities; the nature of the sewage system; the state of electrification; hospitals, medical care; and details of the military forces available.

The teams’ war plans were, when finalised, first approved by the fleet commander-in-chief and then submitted to the Department of Navy. There they were stowed away, not, it would seem, seeing the light of day for the next nine decades. They were never apparently updated or revised.

So, what should we make of these plans?