- Author

- Dunne, Mike

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2006 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Admired by friend and foe alike for his exploits as commander of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Destroyer Squadron 2, Tanaka gained everlasting fame as their greatest leader of destroyer forces. He became known to all as Tanaka the Tenacious.

He is particularly remembered for his exploits with the famous ‘Tokyo Express’, a small force of destroyers that ran supplies and soldiers to Guadalcanal with alarming regularity, while wreaking a considerable amount of destruction on the allied forces who were doing their best to stop him.

While not particularly enamoured of the work he was tasked with and highly critical of his superiors’ conduct of the war in the South West Pacific area, Tanaka nevertheless carried out his duties with great skill and daring.

Raizo Tanaka graduated 34/118 in the 41st class at Etajima Naval Academy and progressed steadily through the ranks, coming to concentrate on torpedo warfare and most notably on the testing of the newly developed Type 93 ‘Long Lance’ torpedoes. He was to become most adept at making full use of the awesome capabilities of the Type 93.

Following a seagoing command stint aboard the battleship Kongo he was given command of 2 DESRON, the ‘Close Cover’ destroyer flotilla (Transports) at Midway, and following the loss of this battle was assigned with his ships to form part of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s Battle Group operating in the SWP area, notably in support of the capture of Guadalcanal.

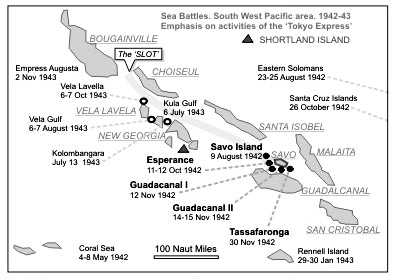

The extreme difficulties inherent in supplying and supporting General Hyakutake’s forces on Guadalcanal led to Tanaka’s first class destroyer Squadron becoming a fleet of 36 knot transports. Charging down through the ‘Slot’ under cover of darkness Tanaka’s destroyers succeeding in running supplies, weapons and troops with alarming (for the Allies) regularity and success. These resupply runs became known as the ‘Tokyo Express’ and were to last until the eventual evacuation of Japanese forces on 14 January 1943.

His usual, very successful, tactic was to assemble his ships near Shortland Island, just out of range of Henderson’s SBD Dauntless aircraft and wait for dusk before racing through the ‘Slot’ to Guadalcanal.

The USN tried a number of ambushes, but these usually resulted in a triumph for Tanaka.

The Solomon Islands, of which Guadalcanal was a key component, were to be the scene of the Pacific War’s lengthiest and most bitterly fought campaign. Including the fighting in and around Guadalcanal, more than a dozen battles raged in these confined waters, mostly as night surface engagements where the weapons and tactics of the IJN were able to prevail time and again.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, they were up against a foe who was quick to learn from past mistakes and willing to accept heavy losses in order to eventually prevail.

Activities of the Tokyo Express

May 1942 saw the Japanese consolidating their hold on the Solomons, from which they could threaten not only the New Hebrides and Fiji but also Australia itself. Encouraged by their great success of Midway, the Americans resolved that the Solomons would be the point at which the seemingly inexorable enemy tide would be stemmed. A battle of wills thus developed, with its centre on the strategically unimportant island of Guadalcanal, and the contest finally cost both sides dearly.

By early July the Americans were getting ready to mount their very first amphibious operation of the war, an operation urgently brought forward when aerial reconnaissance showed that the Japanese were preparing an airstrip on Guadalcanal and a seaplane base on neighbouring Tulagi. The landing, virtually unopposed, took place on 1 August and by 9 August, apparently only mopping-up operations remained for the Americans.

Any complacency was rudely shattered on the night of 9 August when Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s cruisers bore in to inflict a bloody defeat off Savo Island on the naval forces covering the landing. This tactical victory for the IJN was, however, a strategic success for the USN, because Mikawa failed to attack what should have been his prime target, the transports engaged in landing US Marines. The transports quickly withdrew to safety, leaving 16,000 US Marines ashore. Working feverishly in the damp, enervating heat their engineers had the incomplete Japanese airstrip open for business by 15 August and named it Henderson Field. It was to play a crucial role in the forthcoming battles for the island and its vital airstrip.