- Author

- Brown, Andrew, Commander, RNZN

- Subjects

- History - Between the wars

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2008 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Many students of world history would be aware of the security treaty between Australia, New Zealand and the United States of America dated 1 September 1951, commonly referred to as the ANZUS Treaty. The ANZUS Treaty was an Australian initiative and, although it has undergone some changes in the way it operates at a practical level, successive Australian governments have accepted that the ANZUS treaty underpins Australia’s national security.

Of course, it does not only benefit Australia; the United States (US) clearly sees value in the treaty. Although many articles and papers have appeared about the circumstances that gave rise to the creation of ANZUS and of its potential effect in range of scenarios, few commentators appear to have acknowledged that the ANZUS Treaty was not the first Cold War agreement for mutual defence and support between the US and Australia.

In 1950 Australia appreciated that the United States Navy (USN) was the dominant naval power in both the Pacific and Indian Oceans. However, experience from World War II had shown that, from an operational perspective, Australia was a long way from the US headquarters (either on American soil or in Japan), and even further away in terms of US strategic thinking. Furthermore, the Korean War was underway and there was a general intensification of the Cold War, especially in Asia with the recent creation of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949. The possibility of another world war was very real, and Australia faced threats to its security, including to its maritime trade. As is the case today, maritime trade was fundamental to Australia’s security and prosperity, yet there was no certainty that the US either would or could assist if our maritime trade was threatened.

At the time, any analyses of potential threats to Australia’s strategic interests effectively equated to threats to British interests, and were soon concentrated on the Malay Peninsula. Consequently the threat to sea lines of communication in British South East Asia resulted in the creation of the Australia, New Zealand and Malaya (ANZAM) Region in 1950. This region largely overlapped with the Royal Navy’s Far East Station and the Australia Station, and was centred on Singapore. With the declaration of ANZAM came the establishment of a higher command structure that would operate from Australia (and be largely Australian-staffed) in the event of war. ANZAM itself was not a treaty but rather an agreement between participating naval forces on certain higher command functions necessary for the protection of maritime trade. Its overall intent was to establish a coordinated Allied response to any attacks on merchant shipping within the ANZAM Region. Understandably, its creation was viewed by the US with some concern.

The US has never entered in treaties of mutual defence and support lightly. In 1950 it did not view Australia as within its area of responsibility, nor did it believe it should in any way automatically safeguard Australia’s sovereignty or its interests. The declaration of the ANZAM Region, however, affected that position at a practical level. Within the US Government, neither the State Department nor the Joint Chiefs of Staff formally altered their view of the relationship between Australia and the US, but at the Headquarters of the US Pacific Fleet in Hawaii, the declaration of the ANZAM Region could not be ignored.

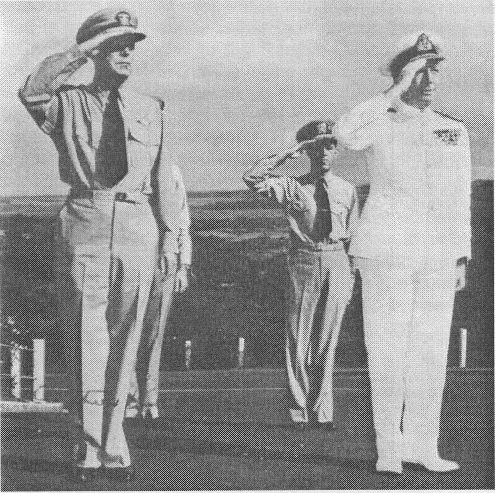

at CINCPACFLT Headquarters, Pearl Harbour, 1951. (RAN)

Australia’s then Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral John Collins, had been seeking agreement with the US Pacific Fleet since 1948 on a raft of matters, all of which were linked, one way or another, to agreed procedures for trade protection, reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare operations in the Pacific area. The US Pacific Fleet staff had politely informed him that it was not interested in discussing such matters. The declaration of the ANZAM Region forced a change in that view as the region overlapped with the US Pacific Theatre, and the very real possibility of confusion and administrative conflict in the event of war was obvious. Further, ANZAM locked the United Kingdom (UK) into the Pacific area as a strategic power, whereas the US had a very firm view as to which nation was to be the strategic power in the Pacific (it should be remembered that the UK would not become a nuclear power until late 1952). As the ANZAM staff was to be supported by and based in Australia, the Commander-in-Chief US Pacific Fleet (CINPACFLT), Admiral Arthur Radford, was obliged to deal with Australia and specifically Rear Admiral Collins in order to resolve these issues.