- Author

- A.N. Other and NHSA Webmaster

- Subjects

- WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Armidale I, HMAS Voyager I, ML814, ML815

- Publication

- December 1994 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In February 1942 when the Japanese army invaded Timor a small band of Australians – the `Sparrow Force’ – took to the mountains and began a guerilla war against the Japanese Army. It was to last for years, and much of that story of endurance and despair is still unknown.

In 1942 the eyes of the world were focussed on great disasters – armies and fleets locked in combat, populous countries laid waste, `impregnable’ fortresses reduced, and ancient cities in flames. And it is not surprising that, after the loss of Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, our Eighth Division, the Perth and Yarra, the Australian authorities had written the Sparrow Force off.

But they were still fighting and in desperate need, and the RAN and RAAF were to make valiant efforts to succour them. Most of these operations were carried out at night in great secrecy. Some were costly and bloody and ended in disasters for the RAN.

In the early days the seaborne supply runs were carried out by two small slow Customs and Fisheries Protection vessels which repeatedly made the dangerous 300 mile crossing to Timor, anchoring outside the surf on open beaches, but they were unequal to the task, and, in addition to more Australian vessels, some American submarines and a Dutch destroyer were called in to assist. With Japanese planes and ships dominating the Timor Sea the RAN suffered losses in the corvette HMAS Armidale and the destroyer HMAS Voyager.

Early in 1943 two of the RAN’s new Fairmiles HMAMLs 814 and 815 – arrived on the scene. These sleek little 112-foot warships, built in Sydney and Brisbane, were each manned by 19 men with an average age of about 21. Although armed with one two-pounder gun, one twenty-millimetre canon and machine guns, they offered little threat to a Japanese destroyer or a flight of enemy bombers, but in July 1943, being judged more expandable than corvettes and destroyers, they were selected for a special `cloak and dagger’ operation to rescue a large number of neutral Portuguese citizens from the Japanese on Timor – a voyage of 800 miles which took five days.

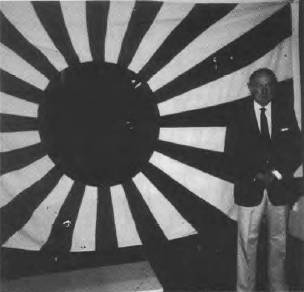

Just before ML 814 sailed from Darwin she was given a fake Japanese naval ensign to fly as a `Ruse de Guerre’. (Sailing under false colours sounds better in French.)

Fifty-one years later, on 7th October 1994, something of the story of what happened on that operation and the subsequent history of the flag was revealed in Canberra, when the ensign was presented to the Australian War Memorial in the presence of some of those formerly young men who are now in their eighth and ninth decades.