- Author

- A.N. Other and NHSA Webmaster

- Subjects

- WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 1994 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Battle of Coronel – 1914

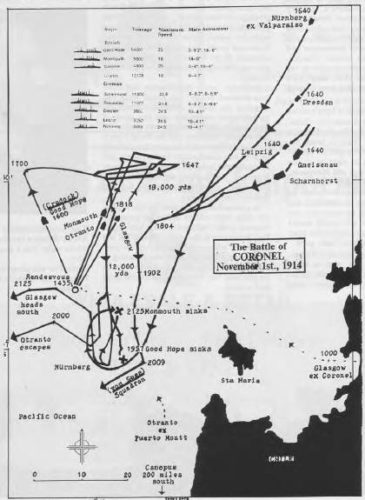

Although the Royal Navy outnumbered the German navy by a huge margin in 1914, British strength was concentrated in the North Sea, leaving small isolated detachments on overseas stations to protect shipping and strategic targets such as cooling stations. Although the German Far Eastern Squadron’s base at Tsingtao in China was neutralized by Japan’s entry into the war on Britain’s side, the squadron’s cruisers slipped away to inflict whatever damage they could to British commerce. Under their bold and dashing leader, Count Maximilian von Spee, the armored cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the light cruisers Dresden, Leipzig and Nürnberg made a landfall on the coast ‘of Chile in October 1914, when they took on coal in a secret rendezvous with German colliers.

The British soon had wind of Spee’s arrival on the Pacific coast, and Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock took his South America squadron around Cape Horn to bring the German ships to batty. On paper his squadron was stronger, since in addition to the armored cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth, the light cruiser Glasgow and the armed merchant cruiser Otranto he could also count on the battleship Canopus. But the battleship was too slow to keep up with his squadron, the two big cruisers were old and weakly armed and the Otranto was a vulnerable ocean liner hurriedly armed with eight 4.7-inch guns.

When the two squadrons met on 1 November it was late in the day, and in heavy weather. The British ships were silhouetted against the setting sun, while Spee’s ships grew steadily harder to make out against the darkness. The British admiral doggedly tried to bring his squadron’s firepower to bear but HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth were raked by accurate enemy gunfire without being able to make an effective reply.

The Good Hope sank at 1957, after being completely silenced by an internal explosion. The Monmouth turned her stern toward the rising seas in a desperate attempt to stay afloat, but her captain gallantly ordered the light cruiser Glasgow to make her escape rather than try to take the Monmouth in tow. Having largely escaped the attention of the German cruisers, the Glasgow was able to get clear and re-unite with the Otranto.

Battle of the Falklands Islands – 1914

Although small detachments had been overwhelmed before, the Royal Navy had forgotten the taste of defeat in a century of unchallenged supremacy and the sense of humiliation after Coronel was acute. To restore both their own and the Royal Navy’s prestige the Board of Admiralty immediately ordered two dreadnought battlecruisers, the Invincible and Inflexible to head for the South Atlantic, where they were to form the nucleus of a powerful squadron to find and destroy Spee’s cruisers.

In a remarkably short time the two 18,000 ton ships were refitted and sailed across the Atlantic to the Falkland Islands, arriving at Port Stanley on 6 December 1914. What was even more remarkable was the total secrecy of the operation; von Spee was planning to attack and destroy the coaling station, with no idea that two very powerful capital ships had arrived.

On the morning of 8 December 1914 the German ships approached Port Stanley without suspecting that anything was wrong. At first it was assumed that the clouds of smoke drifting across Port Stanley’s anchorage were from burning coal stocks, and only when it was too late did a lookout report that he could see tripod masts – the trademark of dreadnoughts. The old battleship Canopus was the first to open fire, from the mudflats in the harbor, where she had been beached to provide a steady gun-platform.

Although critics were to say later that von Spee might have done better to hold his course and try to damage Vice Admiral Sturdee’s battlecruisers as they emerged from the harbor entrance, the German commander headed southeast as fast as he could go, for he must have known that his hours were numbered. The action quickly turned into a long chase, with the British battlecruisers building up to full speed and overhauling the Germans slowly but surely, and Rear Admiral Stoddart’s armored cruisers bringing up the rear. The British had the day in front of them, the weather was cold but clear, and time was on their side.