- Author

- Morris, Kenneth N., Surgeon Lieutenant, RAN

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

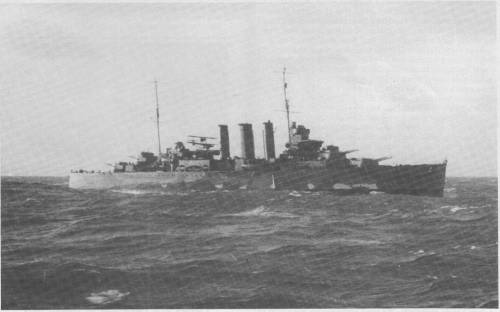

- HMAS Canberra I

- Publication

- July 1992 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Extract from a letter written by Surgeon Lieutenant Kenneth N. Morris to a medical colleague following the sinking of HMAS CANBERRA on 9th August 1942. (Citation: AWM PR 82/86)

“Doubtless you will want to hear my version of the show. I shall endeavour to give you an outline of the affair – but of course so much happened that even now I haven’t remembered half of it – and were I to write in detail that which I can remember I would have to be engaging a stenographer and sending you weekly instalments.

Of course I can’t give you many details about how we came to be in such a hot spot – but we had been protecting transports in the Solomons for three days during which we had been bombed pretty frequently. Once they sent thirty torpedo bombers in at us – they didn’t hit a ship and only two planes survived the run.

Waiting for the bombers is not my idea of a rest cure. I, of course, live below the deck with my first aid party. In the tropics with everything shut down, and wrapped up in antiflash gear, the heat is practically unbearable. When the alarm sounds we crawl into our overalls, gloves, helmets, goggles, etc. and lie down in the most sheltered spot to be found – if someone hasn’t got there before you. When the planes are a fair distance away they let go with the 8” guns – making a racket such that for a moment everyone thinks we have been hit by about six torpedoes, Then the 4” H.A. stuff starts to let go as fast as they can pump shells out – at this stage you know that the planes are still a fair distance away. Then the Oerlikon 20mm automatic weapons start and you sweat in real earnest because you know that they are just starting to let go their bombs or torpedoes – then as they start to get really close the .5” machine guns and then the .303 machine guns open up and you know that if you’re going to be hit – now’s the time.

Then the racket suddenly stops and you know that they have passed. Then you start swimming out of the pool of perspiration that you have been lying in (relieved always to find that it is only perspiration) and go up on deck to find out if there are any wrecked planes to be seen. If one could only see what was going on things wouldn’t be so bad – but the imagination left to itself tends to run riot.

The big stoush when we caught it was at 01.50 on 9 August 1942. We had all been living at our action stations for the three days that we had been there and I was asleep on a mess table when the alarm went. I dragged on a pair of overalls and shoes over the underpants in which I had been sleeping. Some casualties came staggering in much to my surprise as I didn’t even know that we had been hit. At that stage we got hit in both boiler rooms which meant that all the power, light, water etc. was cut off – and we could not train our guns or fight our fires. I fortunately had a torch with the globe, etc. attached to a head band so I was able to work in the light of it. Then they gave the order to prepare to abandon ship and we had to get our casualties up on the deck, We had only been up there about ¼ hour when it started to pour with rain.

At one stage I found myself standing underneath the aircraft which was on fire – the flames were just starting to creep along the wings and there were 4 100 lbs bombs attached to the wings waiting to drop at my feet when the wings fell off. I moved off with rare speed. The bombs did fall later but it wasn’t a long enough drop to set them off.

At various stages during the game we would be playing hide and seek with our own 4” ammunition – a lot of which we stored in ready use lockers on the deck. As the fire reached a new locker everyone would dive behind the nearest cover – anything from a ½” rope to a gun turret.