- Author

- Baker, K.G.

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

It was a little before 12 o’clock on the morning of Trafalgar that Nelson directed his famous signal to be made. The VICTORY was at the time about a mile and a half from the enemy’s line, slowly forging ahead on the faint breeze, under every sail that could be set. On the flagship’s quarterdeck, Nelson and Captain Blackwood, the officer commanding the frigate squadron, were walking together, watching the long straggling array of French and Spanish ships as they slowly drew across the course of the British line.

Presently Nelson asked Captain Blackwood what he would consider a victory. “If fourteen of the enemy are taken,” was the reply. “I shall not be satisfied,” rejoined Nelson, “with less than twenty.” Then after a short pause during which the Admiral seemed to be musing, he turned to his companion again, “Don’t you think,” he asked, “It seems that a signal is wanting?”

“No my Lord,” Blackwood answered, “I think nothing more is needed; the whole fleet seems to understand what we are about.” But the Admiral had already made up his mind, and turning to walk along the quarterdeck, he stepped up the poop ladder to where the Flag Lieutenant, John Pasco, who was in charge of the signal department, was standing.

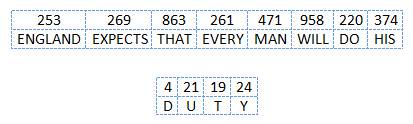

What passed, Lieutenant Pasco has told. “His Lordship,” he related, “came to me on the poop, and after ordering certain signals to be made about a quarter to noon, said, “Mr. Pasco, I want to say to the Fleet, ‘England confides that every man will do his duty.’ He added, “You must be quick, for I have one more to add, which is for close action.” I replied, “If your Lordship will permit me to substitute ‘expects’ for ‘confides’, the signal will soon be completed, because the word ‘expects’ is in the vocabulary and ‘confides’ must be spelt. His Lord ship replied in haste and with seeming satisfaction, “That will do, Pasco, make it directly.”

The immortal message then went up, in twelve separate hoists, Lord Nelson’s word being rendered according to Sir Home Popham’s Telegraphic Code – which had been supplied to the fleet as an experiment – with the numerical flags of the Admiralty official Day Signal book (the 1799 issue then in use).

As the last hoist was hauled down, Lord Nelson, who had meanwhile returned to where Captain Blackwood was standing exclaimed: “Now I can do no more. We must trust to the Great Disposer of all events and the justice of our cause. I thank God for this great opportunity of doing my duty.” When the Admiral’s message, “had been answered by a few ships in the van,” says Lieutenant Pasco, “he ordered me to make a signal for “Close Action” and to keep it up. Accordingly, I hoisted No. 16 to the main topgallant mast head and there it remained until shot away.”

It is noteworthy, by the way, how Nelson in each of the three actions in which he held chief command made No. 16 – “engage the enemy more closely”, his special battle signal. With No. 16 at the VANGUARD’s main topgallant mast head he triumphantly led his “Chosen Band” at the Nile. It was No. 16 that at Copenhagen he bade his signal officer – after he himself put his telescope to his blind eye and jocularly declared that he could not see Sir Hyde Parker’s permissive signal to discontinue the action – to “keep flying” and to “nail to the mast”.

Now finally he “sailed to imperishable glory in the VICTORY with the same No. 16 once more hoisted aloft.”