- Author

- Goldrick, James, Commodore, RAN

- Subjects

- Ship design and development, History - Between the wars

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2011 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

(A lecture delivered to the naval history course of the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy)

FAILURE

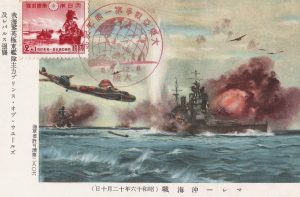

The popular picture of British strategy and the Royal Navy between the wars is of failure, failure to understand strategic reality in the form of the emergent challenges of the Japanese, the Germans and the Italians and failure to comprehend the implications of the rapid pace of technological development and the massive consequences for maritime operations of such innovations as aircraft and submarines. All of this failure, it can be argued, in the disaster of the destruction of Force Z in December 1941, when the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse were overwhelmed in the absence of their own air cover by repeated attacks by Japanese long range gravity and torpedo bombers.

COMPLACENCY

There is some truth in this picture. There were complacency, lack of imagination and arrogance within the British government, defence machinery and the Royal Navy of the 1920s and 1930s and these defects certainly contributed to some of the failures of the British when the Second World War started. But there were also many factors which were beyond the control of strategic policy makers, force structure planners and operational commanders and against which they struggled with considerable success.

THE WORLD EMPIRE

When one contemplates the British situation, it is essential to consider the world as a whole because the British Empire was, literally, a world wide one and had to assess its strategy and its policy in a world wide context. Thus, for example, the maintenance of balance of power in Europe was not for the British an end in itself, however desirable, but a means to a greater end – the preservation and well being of the British Empire and Britain’s commercial and financial position – two aspects of British policy that were not identical but were very closely linked. For example, although British possessions within South America were very limited, their commercial holdings and investments were not and the profits made from South American ventures and the trade links with that part of the world were as significant to British thinking as any other.

ANGLO-AMERICAN COMPETITION

This brings me to another point in considering the British position, particularly from the vantage point of the Second World War and the Cold War that followed. Ideology, with the exception of fears of Communism and the nascent but still weak Soviet Union, was not really a factor in international politics until well on into the 1930s. Despite the First World War and any shared linguistic and cultural heritage, the United Kingdom and the United States perceived each other as much as strategic competitors as partners. Commercial competition between British and American interests was a reality around the globe and it was coloured by the anti-colonialism of the Americans that was partly idealistic and partly engendered by a desire to improve America’s position in a highly competitive environment. Multinationals and globalisation have been with us for a long time.

This did not mean that the British and Americans were enemies – even if the American Naval War College did include in the 1920s games against the British in its curriculum for strategic planning under the designation of ‘War Plan RED’ as the alternative to those against the Japanese which were designated ‘Plan ORANGE’. But it did mean that the British and the Americans were not very good friends.

THE BALANCE OF POWER IN THE 1920s

The next point is that the balance of power in Europe in the 1920s was not that of a decade later, particularly in regard to Germany. While a German renaissance was feared, the fact was that German naval power had been so restricted under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that it could not be considered as being a serious issue for the Royal Navy. Northern European security had many more land implications than it did maritime until the advent of the Nazis in 1933 and the start of German rearmament. British maritime security was concerned more with problems of the Mediterranean and very much more with problems of the Far East – the threat posed by the Japanese and their powerful fleet.

FAILURE AND TECHNOLOGY

Another part of the image of British failure is that of an alleged failure to exploit technological opportunities. Here, too, there are real difficulties in sustaining a thesis of systematic British failure and certainly challenges in according particular culpability to naval planners. The first point is that in understanding the effects of technological change upon military forces one has to remember the delicate balance between present capability and potential for the future and the relationship of both to strategic warning. What do I mean by this? As a military force, if you sacrifice your capacity to operate effectively in the short term in favour of spending your money on capabilities which will only give you a return a decade ahead – and which you cannot be 100% sure will be effective – you are going to look pretty silly if a contingency arises in the meantime.

REVOLUTIONS IN MILITARY AFFAIRS

And here is another point about technological change. A revolution in military affairs is NOT about a particular innovation such as an aircraft or radar making a difference to the way that war is fought. It is the way in which such innovations are utilised that determines whether a revolution occurs. In the case of the Emperor Napoleon, for example, the revolution which he engendered in terms of improving the mobility of land forces and utilising in combination the arms of infantry, cavalry and artillery did not depend upon any significant new technology – it was the way that he used existing technology that counted.

THE AIRCRAFT CARRIER

Let’s look at the aircraft carrier. Please do not have the picture of the American super carriers in your mind when you think about the aircraft carrier – do not even have the picture of the attack on Pearl Harbor, of the Coral Sea or of Midway in your mind when you think of the 1920s and even most of the 1930s. Why? Because it took the best part of twenty years after World War I for the combination of new technological systems AND procedures and proven in-service capabilities to come together to make effective weapon systems. It really only happened from about 1937 onwards with the advent of metal skinned monoplanes with more powerful engines. The British were, for many reasons, three or four years behind in this development, a few years which in strategic terms were to prove critical.

Let me give you an example of the problems which British aircraft carriers had around 1930. First, carrier aircraft could not easily fly at night – that means that the aircraft carrier was ineffective up to 50% of the time. Second, carrier aircraft and carrier operations were weather limited (as were shore bases, a point sometimes neglected by advocates of shore based air power). If the wind was above about Force 6 with an accompanying high sea state, they couldn’t fly and they couldn’t fly in low visibility. In northern European waters, the combination of these two factors probably accounted for another 15% (by the most favourable estimate). Thus, you have a powerful and very expensive weapon system (and aircraft carriers with their air groups cost a lot more than battleships) which is ineffective for up to 65% of the time. This perhaps explains why aircraft carriers of the 1920s were armed with the same sort of guns as a cruiser. As exercises showed, they often had to defend themselves. It also partly explains why carrier borne air flourished in the clearer air of the Pacific where in any case the distances were much greater and the potential land air bases much more widely distributed.

THE BRITISH AND THE RAF

The problem gets worse. If we look at the aircraft which were available in the 1920s and early 1930s, single engine, cloth skinned biplanes, they suffered from limited speed and minimal range. Furthermore, the British had a problem which was a direct result of the creation of the Royal Air Force which had removed a substantial proportion of the aviation expertise from the Royal Navy on its formation in 1918. Because the British had so few aviation experienced senior officers, admirals and captains had to depend very much upon the advice of their juniors who were actually flying the aircraft. In the United States and Japan, by comparison, many of the aviation ship commanders were themselves aviators. What happened was that the British suffered from conservatism from the bottom. Because the British admirals were not themselves experts, they were much less willing than the Americans or Japanese to take risks and push their subordinates into extending the operational envelope and accepting greater risks. Thus, the British were much more cautious in the way they operated. For example, British carriers would not recover an aircraft while there was another one still on deck – each aircraft had to be struck down into the hangar before the next was landed on. This meant that the British took up to four times longer than the Americans did to get their air groups back on board. This of course meant that the effective operational range of the aircraft was reduced, particularly when operating in large numbers, because they had to keep a reserve of fuel to wait for recovery. The risk of one aircraft running into another if it did a bad landing on deck was something which the USN and the IJN would accept.

There were other, similar problems. But the consequence of them all was that British operational ranges were about one third lower than for the Americans or the Japanese. And when this meant a reduction from 180 miles to 120 miles, the consequences were profound.

AN EXERCISE IN THE ATLANTIC

Let us look at a theoretical exercise in 1932, in which a carrier is pitted against a cruiser force in the Atlantic. It is one hour before dawn and, at 0500, each side detects radio transmissions from the other and thus knows the bearing but not the range of the opposition. Although each has to assume that the opposition is in the vicinity, they are in fact 100 miles apart. Each determines to launch a scouting aircraft at dawn since their aircraft cannot operate at night. In each case, the scout is a Fairey IIIF biplane; the cruisers’ machine is a float plane, the carrier’s a land plane. The weather is clear and the sea slight, apparently ideal conditions for air operations at sea.

But note the first problem for the carrier – the wind is from the west, which means that the ship must steam towards the cruisers when launching or recovering aircraft. If she is operating any kind of air patrols this means, at best, that she cannot make ground to keep her distance from the cruisers. In reality, she could well end up making ground to the west, despite her best intentions.

If all the equipment works and accepting favourable times for the carrier to recover the scout and organise an eighteen aircraft strike (which against a three cruiser force is a threat but not necessarily a decisive one), we get the result that the carrier’s aircraft would be able to achieve a strike when the cruisers are still out of range at 32 miles.

But, if a radio fails in the scout (and the airborne radios often did – even in 1942 the course of the Battle of Midway was arguably determined by the failure of a single Japanese radio), the equation becomes very different. The cruisers are approaching gun range at fourteen miles from the carrier before her aircraft are in position to strike. See the problem?

THE RN AND FIGHTER AIRCRAFT

Let me look at another aspect. The Royal Navy chose in the late 1930s to reduce the number of fighter aircraft in its carriers, concentrate on strike and reconnaissance aircraft and protect its carriers with a heavy armoured deck and an increased anti-aircraft gun armament – accepting that the armoured deck and gun armament meant that there was less capacity for aircraft, thereby apparently exacerbating the lack of fighters.

This seems, on the face of it, to be a pretty stupid approach. But was it, when the decision was taken in 1935? In the first place, one of the driving reasons was warning time. In the 1920s, fleets at sea gained the warning time necessary to launch fighters and get them high enough to be of use by deploying cruisers and destroyers on the horizon – in touch with the main force but maintaining radio silence. There they kept a lookout for approaching aircraft, breaking silence to report when they made a sighting. This worked with biplanes which were advancing at about 100 or so knots. But it did not work with monoplanes which were 50 knots faster because there was simply not enough time to get the aircraft up once the warning signal from a ship 20 miles away had been received of a force 10 or so miles further out. The difference here between 20 or so minutes and 12 or so minutes was vital. What changed the equation? Radar, something barely dreamed about as a possibility for seagoing ships as late as 1935 but which was providing effective early warning to the British fleet in the Mediterranean in 1940.

Before the advent of radar, only the very biggest carriers could have enough fighters to maintain a permanent airborne patrol throughout daylight hours – and, although the British possessed some big carriers, they never really had enough aircraft because they didn’t have enough money. And single seater fighters were not particularly useful – they had a limited role, limited range and not much of an ability to navigate over long distances over the sea.

CARRIERS AND BOMBERS

Another point is that in 1935 it did not appear as though long range aircraft would have the capacity to carry bombs greater than about 500 pounds (approximately 250 kilograms).[1] In these circumstances, it was possible to design ships which carried sufficient armour that the bombs could not penetrate. This is what the British did accepting the reduced aircraft carrying capacity which was part of the final armoured carrier design. By 1940, the operational carrying capacity of the new aircraft entering service in the world’s air fleets was about 1,000 pounds, as the British discovered to their cost – too much to armour effectively against in any reasonably sized ship. Nevertheless, despite the disadvantages of the armoured deck, it was true that British ships survived attacks by aircraft that would have sunk the aircraft carriers of other nations. This was well demonstrated during the kamikaze attacks in the Pacific in 1945 when British carriers literally brushed the debris of crashed aircraft off their decks while some American carriers were so badly damaged that they never again saw operational service.

THE BALANCED FLEET

Contrary to the received wisdom, the picture of the Royal Navy’s investment programmes between 1919 and 1939 is not one in which all the available money was poured into renovation of the battleship force. In fact, during the years between the wars it is now clear that in real terms the United States Navy spent more than half as much again as the British on the renewal of a battleship force which was the same size as that of the British.

The Royal Navy’s picture is on fact one of careful balance between all arms of the fleet. Cruiser construction was only interrupted by the Depression. Destroyer building programmes were begun at the end of the 1920s and also interrupted only by the Great Depression. The submarine building programme was also substantial and was marked by many efforts to experiment and innovate with new designs – such as a cruiser submarine with 130mm (5.2″) guns – not as silly as it sounds – and large minelaying submarines.

The fact that the British did not see the battleship as the sole arbiter of naval power is indicated by the resources which went into aircraft carriers – there were three major conversions in the 1920s which became the large carriers FURIOUS, COURAGEOUS and GLORIOUS, the ARK ROYAL was laid down in the early 1930s and the rearmament programme of the late 1930s included six large aircraft carriers by comparison with five battleships. Aircraft carriers and their air groups, it should be noted again, cost much more than battleships.

Indeed, as I look at the tactical school of the Royal Navy between the wars and the way in which they intended to fight, I am struck by the extent to which the British were seeking to overcome what they perceived as inherent technological disadvantages – and disadvantages in numbers – by innovative tactical thought and the combination of all arms of maritime warfare. For this reason, we see the Royal Navy working hard on night fighting, something about which it had been less than enthusiastic before Jutland. We do see a lot of work on surprise attacks, on seeking out the enemy where he would be most vulnerable.

This manifested itself in all sorts of ways. In the Abyssinian Crisis of 1935-36, the British Mediterranean Fleet had worked out a comprehensive plan for an air attack on the Italian Fleet in its bases, a plan that was to be revived and brought to a triumphant conclusion at Taranto in November 1940. The China Fleet of the 1930s, which did not have battleships and possessed only one aircraft carrier, nevertheless had no less than 15 submarines on strength, the most modern that the British possessed and more than the operational submarine forces of the Home and Mediterranean Fleets combined. Why should this be so? Because, until reinforcements could be brought out to the Far East, the submarines would be by far the most effective means for the weaker naval power – in this case the British – could slow down the onslaught of the stronger, the Japanese if the latter embarked upon an attack of British territories.[2]

These are not the dispositions of a Navy totally fixated on battleships.

THE GREATEST NAVAL DISASTER

I think that there are several factors that have caused us to be unduly critical of the British. The first, I believe, is that the alliance with the French was a fundamental construct of British strategy throughout the 1920s and 1930s and that it was the fall of France and the opening of the French ports to the German submarine and air campaigns that was in fact the greatest naval disaster that the British have ever suffered. It is a matter of looking at maps. If the Germans did not have the direct access to the Atlantic that they enjoyed from 1940 to 1945, then the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’ would have been as much a battle of Northern European waters and much of the British anti-submarine effort could have been conducted much closer to home. When we look at the FLOWER class corvettes of ‘the Cruel Sea’ and the fact that they were much too small for the Atlantic in 1941, we should remember that they had been developed with a different strategic construct in mind. It is worth noting, for example, that although the Germans enjoyed some spectacular successes in 1939 with their U-Boats, notably in sinking the carrier COURAGEOUS at sea and the battleship ROYAL OAK at anchor in Scapa Flow, they also suffered greater proportional losses in the same period than they did until 1943 when the tide turned in the Atlantic. Furthermore, the French possessed their own substantial Navy, one that could help on the trade routes around the world and, equally to the point, neutralise the Italian Fleet of equivalent size and capability.

THE LIMITS OF BRITISH TECHNOLOGY

The second point is that British technology on a national basis itself had considerable limitations. The British failed profoundly in their attempts to produce adequate anti-aircraft weapons and a systematic underestimation of the threat was at least partially responsible for this. This underestimation, to be fair, was partly caused by an intelligence failure in imagination which has in recent times been termed ‘projection’. Because the British were so limited in many of their achievements with aviation over the sea, they could not believe that others were much further advanced. When the Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk in 1941, this was the first inkling that the British had received that the Japanese aircraft could operate at such ranges from their bases.

THE LACK OF MONEY

But much of the failure was caused by the inability of the British to produce all the equipment that they needed. One fundamental cause, which I have already suggested by implication, was the lack of money. Look again at the map of the world. Fundamentally, the British had more calls on their day to day resources and more requirements to sustain operational readiness than did either the Americans or the Japanese or any of the Europeans. They had to maintain a chain of naval bases and repair and support facilities throughout the world, both more distributed and more numerous than any other naval power. Thus, although they apparently had parity with the USN and superiority over the IJN, they had consistently to devote more of their money to operations and less to modernisation and innovation than did any of the others. This is one way in which the Americans were able to spend so much more on modernising their battle fleet than the British, even when it appeared that the British had a larger budget.

NATIONAL CAPABILITY

The next problem was national capability. The anti-aircraft fire control system with which the British entered the Second World War was what is called a goniographic system which basically predicted the fire control solution based on the target aircraft continuing on a steady course, speed and height from its previously measured position – consistent movement from one point to another. Aircraft that are attacking you, just as ships that are in the same situation, rarely approach their targets on a steady course, speed and height. This goniographic system was just good enough against slow moving biplanes, it was effectively useless against monoplanes. What was needed was the type of tachymetric system which the United States and the Netherlands succeeding in developing, a system which computed the future position of the target by calculating the curves of movement –an integrating calculator in other words. The British eventually adopted the American system in default of their own – but a number of experts have admitted that they would probably not have been capable of developing and manufacturing such a system even if they were aware of what was really needed.

British marine engineering had been overtaken by the Americans and many of the Europeans and the Japanese in a number of areas, such that the much greater American reliability and range came as a real shock to the Royal Navy (and to the RAN) during the Pacific War. This overtaking was as much the case for the British merchant fleet – possibly much more – as it was for the Royal Navy and it was another indication of a national malaise in terms of investment in emergent technology in modern industry, a malaise that was itself the result of a host of social, economic and political issues.

CONCLUSION

I am not trying here to be an apologist for the British and for the Royal Navy. But I am trying to make the point that there is a great deal of difference between stupid people wilfully doing stupid things and intelligent people hard pressed by circumstance who were seeking to act in the best interests of an over extended Empire. They had to act on the information available, they had to act within time constraints and they had to live – and die – by the consequences of their decisions. Let me conclude by quoting Admiral of the Fleet Lord Chatfield, who as First Sea Lord from 1932 to 1938 was responsible for so much of the Royal Navy’s effort to prepare for the coming war. When the question of future battleship construction was being examined in 1935, he was asked by Lord Halifax to put to him succintly the case for such ships. Chatfield replied:

‘If we rebuild the battlefleet and spend many millions in doing so, and then war comes and the airmen are right, and all our battleships are rapidly destroyed by air attack, our money will have been largely thrown away. But if we do not rebuild it and war comes, and the airman is wrong and our airmen cannot destroy the enemy’s capital ships, and they are left to range with impunity on the world oceans and destroy our convoys, then we shall lose the British Empire.’

Footnotes:

[1] Let’s look at some statistics of speed and range over the period:

Fairey IIIF: 120 knots

1927 2 x 250lb bombs

Blackburn Baffin 118 knots

1934 4.5 hrs/87 knots

1 torpedo (18”)

6 x 230 lb bombs

Fairey Swordfish 114 knots

1937 322/86 knots

1 torpedo (18”)

2 x 500 lb bombs

Fairey Barracuda 205 knots

1943 725 nm

1 torpedo (21”)

3 x 500 lb bombs

Grumman Avenger 223 knots

1943 811 nm

1 torpedo (21”)

2000 lbs bombs

[2] UK Submarine Programs 1926-36:

1926 3 O Class (including 2 RAN)

1928 5 O Class

1929 7 O/P Class

1930 4 R Class ( + 2 cancelled)

1931 1 S Class

1932 1 THAMES Class

2 S Class

1 PORPOISE Class

1933 1 S Class

1934 2 THAMES Class

4 S Class

1935 1 PORPOISE Class

1 S Class

1936 2 PORPOISE Class

2 S Class