- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By LCDR Tony Maskell, RAN (Rtd)

The necessity of being able to pinpoint a ship’s position on the globe was becoming a very real problem in the 18th century. British trade and commerce was expanding across sea routes to Canada and the Caribbean, down to the Cape of Good Hope across to India and, through exploration of the Southern Ocean, into the Pacific regions. Many ships and sailors were lost due to the inability to accurately define their position.

During Queen Anne’s reign, Parliament created an Act for ‘The Commission for the discovery of the Longitude at Sea’, which remained in force from 1714 until 1828. Through this Act the Board of Longitude (BOL) was established. Sir Isaac Newton, who was on the Board, summarised the problem to be solved as: ‘…a method of determining the exact time at Greenwich which also involved the motion of the ship, variation in heat or cold, wet and dry, and with the difference in gravity at different latitudes’.

The BOL invited clockmakers to enter a competition for the manufacture of an accurate timepiece that could be used at sea. The requirement was: if at the end of a six week voyage there was an error of 60 nautical miles (nm) or less the prize would be £10,000; if the error was 40 nm or less the award would be £15,000 and if the error was 30 nm or less the prize became £20,000, a vast sum in those days.

John Harrison, a self educated carpenter born in Yorkshire in 1693, built and repaired clocks as a hobby; at the age of 20 he built his first long-case clock with a pendulum. The Astronomer Royal at this time (and a member of the BOL), was Edmond Halley. He supported John Harrison and introduced him to George Graham, a London clockmaker, who lent Harrison the money to make his first ‘sea clock’. At that time, the method of obtaining the longitude from Greenwich required several observations of the moon and stars to calculate the distance.

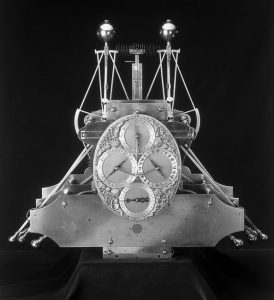

In 1716 Henry Sully, an English watchmaker, had already made a marine clock to determine longitude, but it was affected by the pitching and rolling of a ship when underway and was only accurate in calm waters. It took Harrison five years to build Clock No 1. (H1). The BOL considered this ‘sea clock’ worthy of a trial and in 1736 Harrison was permitted to take it to Lisbon in HMS Centurion and return in HMS Orford. Although this trial was successful the BOL wanted it to be tested on a trans-Atlantic voyage, and in 1741 Harrison built another clock – Clock No 2 (H2). However it was not trialled at sea because at the time England and Spain were at war in the War of the Austrian Succession, and the Admiralty did not want this important equipment falling into enemy hands.

For the next 17 years Harrison spent his time perfecting his third clock No 3 (H3), introducing a bi-metallic strip and caged roller bearing. All these ‘sea clocks’ were quite large and heavy and although accurate were not very practical. Being individually made they were costly and took an immense time in production. The large size was inconvenient in the days of wooden ship construction, when walls were often covered in moisture and there were adverse effects from explosions when ships were at action. Harrison therefore designed and built his fourth ‘sea clock’ which was much smaller, only slightly larger than the pocket watches of the time. He reversed his numbering sequence and in 1759 called this ‘No. 1’ his first ‘sea watch’. However the commonly accepted names of the Harrison clocks and watches, as provided by LCDR Robert Gould, RN are: H1, H2, H3 and H4.

A London clockmaker called John Jeffreys took six years to construct the first ‘sea watch’ to Harrison’s design and under his supervision; This (H4) was 13 cm in diameter and weighed 1.45 kg. Harrison was by now 68 years old and in 1765 he sent it across the Atlantic to Jamaica in HMS Deptford in the care of his son William. The error on arrival was calculated to be one nautical mile.

He waited in vain for the advertised £20,000 prize and another trial was arranged. However this conflicted with the Lunar Distance system promulgated by the new Astronomer Royal, the Reverend Dr Nevil Maskelyne, who was also a member of the BOL. In 1766 the Astronomer Royal turned up at Harrison’s door and took possession of the first three ‘sea clocks’, transporting them over uneven paved roads in an unsprung cart to the Greenwich Observatory, where they arrived in a damaged condition. In 1770 they were consigned to a storage room and not seen again until the 1920s.

In 1772 Harrison appealed to King George III; the King himself ran tests on ‘sea watch 5’ between May and July 1772. He then told Harrison to petition Parliament for the full prize, or else the King himself would appear in person in the House. So it was in 1773 when Harrison was 80 years old that he received the monetary reward, but he never received any official recognition for his life’s work and the immense benefit this produced for future generations of seafarers.

The plot then thickens. Larcum Kendall, an English watchmaker from Oxfordshire, was contracted by the BOL, with agreement of Astronomer Royal Maskeylne, to make a copy of Harrison’s H4, which he completed in 1769. This became known as the K1 ‘sea watch’ and was used by Captain James Cook on his second voyage, along with three other clocks manufactured by John Arnold, but the Arnold clocks failed to perform up to the BOL standards. The cost of manufacture of K1 was £450, a large amount in the 18th century, worth about £30,000 (AUD$46,000) at today’s prices. Captain Cook’s second voyage of discovery lasted three years, from 1772 to 1775, ranging from temperate zones to tropical and Antarctic regions. This Kendal K1 was associated with a number of epic voyages, including Cook’s third voyage, and it was also used in HMS Sirius and HMAT Supply of First Fleet fame.

Kendall informed the BOL that he could produce a simpler clock, the K2, for about £200. This version was used by Captain John Phipps in search of the North West Passage. Lieutenant William Bligh, RN carried K2 in HMS Bounty in 1787 and reported that its daily accuracy was variable. Following the mutiny K2 was taken to Pitcairn Island by Fletcher Christian. Pitcairn Island was rediscovered in 1808 by Captain Mayhew Folger in the American whaler Topaz and John Adams, the only surviving member of the Bounty mutiny, gave K2 to Captain Folger. However, on their way home the whaler called at Juan Fernandez Island where the governor confiscated it. The watch then came into the possession of a Spanish family, who later gave it to Captain Herbert, RN of HMS Calliope. It was then presented to the British Museum and finally K2 is now a prized possession of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

K3, the last watch made by Larcum Kendall in 1774 when he was 53, cost only £100 but it was not as accurate as K1. Cook used the K3 on his third voyage having it installed in HMS Discovery, the consort to HMS Resolution. Captain George Vancouver, RN used K3 in 1791 on his voyage to Northwest America. K3 next left Britain in 1801 with Matthew Flinders, but it was defective. When the ship’s astronomer, John Crosley, became sick and left the ship at Cape Town he took K3 with him. In the next year the repaired K3 was again sent to New South Wales in HMS Glatton under the care of John Inman. Inman used it briefly when establishing a small observatory at Garden Island but he returned to England in 1803 taking K3 with him. All three ‘sea watches’ K1 – K3 by Larcum Kendall are now held by the National Maritime Museum.

John Arnold, a Cornish watchmaker from Bodmin, was the first to call his accurate timepiece a chronometer, and was also the first to ‘mass produce’ them, from around 1782. He had gained experience both in Bodmin and in Holland, and had impressed a gentleman called William McGuire so much, that McGuire gave him a loan to set up business as a watchmaker in Devereux Court London, very near the Old Bailey. When he was 28 he made and presented King George III with an exceptionally small repeating watch mounted on a ring.

The first Arnold chronometer was produced in 1771, by which time Dr Maskelyne had given him Harrison’s Principles of Mr Harrison’s Timekeeper which he had copied from the Board of Longitude. Arnold used a different design with a newly designed escape-ment, and this model came in at a cost of £63. Three of these chronometers travelled with Cook between 1772 and 1775, but only one was still running at the end of the voyage; K1 was still accurate. In 1773 Captain Phipps took an Arnold ‘pocket watch’, as well as two other time pieces, on a voyage to the North Pole; the pocket watch performed well in ascertaining the longitude.

In the period from 1772 to 1775 Arnold took out a patent for his compensation balance and manufactured some 35 pocket time pieces; none of these have survived in their original form as Arnold continued to modify or upgrade them. The Arnold No. 36 was the first timepiece that was referred to as a chronometer, and this term was used to describe any highly accurate watch/clock. This example has been in the National Maritime Museum since 1993.

Arnold’s two patents, one in 1772 and the next in 1782, could only protect his work for 14 years each. Arnold and two other London watchmakers all employed highly skilled workmen. One of these was Thomas Earnshaw, who eventually manufactured chronometers himself. The bi-metallic compensation balance and spring detent escapement designed and made by him have been used in the manufacture of seagoing chronometers since then. Earnshaw produced hundreds of marine and pocket chronometers in the 15 years that his factory at Eltham was without any commercial competition.

In July 1791, on behalf of the Admiralty, Captain Bligh purchased Earnshaw’s timekeeper No E503 for 40 guineas for use in HMS Providence on his second and successful breadfruit collecting voyage. In 1801 Mathew Flinders was well provided with scientific instruments in fitting out HMS Investigator; she carried two Earnshaw timekeepers No. E520 and No. E543 at a cost of 100 guineas each. Investigator also carried two Arnold timekeepers but by the end of the circumnavigation of the Australian continent only E520 was still working. Flinders used E520 on his ill-fated return voyage aboard HMCS Cumberland where he was arrested by the French and imprisoned at Mauritius. In 1805 the French governor released Cumberland’s master John Aken and he was allowed to return to England taking E520 with him, which was returned to the Greenwich Observatory. No more was heard of E520 until 1937 when the records of the then Sydney Technical Museum (now the Powerhouse Museum) show it was purchased from Norman Nisbet of Double Bay. Mr Nisbet, a collector of clocks and watches, may have acquired it on a visit to England. It was not until 1976 when it was identified as the important timepiece used by Flinders.

Earnshaw’s now highly regarded chronometer No E506 was carried aboard HMS Beagle between 1831 and 1836 in her circumnavigation of the world under Captain Robert Fitzroy, RN and with his scientific companion Charles Darwin aboard. Darwin was to become one of the most famous men of his day and Fitzroy became Governor of New Zealand and later helped establish the Metrological Office.

The current naming and numbering of the various iconic timepieces, such as Harrison’s H series and Kendall’s K series, together with those of Arnold and Earnshaw, were not labelled by their makers.

In 1920 most of these valuable timepieces were discovered at Greenwich in a very poor state of repair by a retired naval officer, LCDR Robert Gould, RN. Gould spent until 1933 repairing and resetting them and giving them their unique numbering system.

Harrison’s large clocks H1, H2 and H3 are still running – they do not require lubricants. H4 is repaired but stopped because it requires oil and this over time would degrade it. H5 is owned by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in London. H1 resumed time keeping on 1st February 1933, some 165 years after the Astronomer Royale appropriated it.

So ends a fascinating tale of nautical time keeping.