- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Jerry Lattin

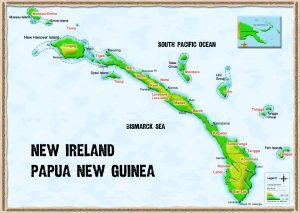

From the 1960s to the 1990s, I spent several periods driving small ships in PNG waters. When there was spare time on passage I used it to explore places that looked interesting on the map. In early 1964, on passage from Buka to Rabaul, I was inspired to visit an anchorage with the charted name of Gower Harbour, just a mile or two north-west of New Ireland’s southern extremity, Cape St George.

It was a deep coastal indentation, sheltered from St George’s Channel to the west by an inshore island, Lambom. The terrain was steep. No major village was evident, but there were gardens and deserted camps on Lambom. Mostly, the hills and island were covered with dense rain forest to the water’s edge. A freshwater stream flowed into the northern part of the bay. As harbours went, it was deep, compact, and well-sheltered. But there was almost nobody there. I felt that this beautiful and tranquil spot held an air of mystery, but there was nothing specific I could point to.

I asked local Rabaul identities about Gower Harbour. Most of them had never heard of it; the few who had, knew nothing more about it than where it was. I pushed it to the back of my mind, and there it stayed for over twenty years.

Then, thumbing through dusty volumes in a bookshop in Sydney’s Newtown in about 1985, I came across The Phantom Paradise by J.H. Niau – and Gower Harbour came out of the closet. A century earlier, the events that occurred in and around Gower Harbour, and various side-shows in other locations, formed a human tragedy on a scale befitting grand opera.

The Expeditions of the Marquis de Rays

German and British colonisation of New Guinea and Papua respectively happened in 1884. Scattered European settlement by missionaries and traders had already begun before then, but it occurred when there was no established government – above the village/tribal level at least – anywhere in what is now PNG.

In the 1870s a French adventurer who styled himself Marquis de Rays devised a plan to establish a colony based on the place now called Gower Harbour. Even then, the place was a regular port of call for Pacific Ocean whalers – under the name Port Praslin – because it had reliable and easily-accessible supplies of fresh water. The Marquis named his proposed colony La Nouvelle France, and renamed the harbour Port Breton. The Marquis himself would become King Charles I of La Nouvelle France. Buyers of sufficient land in the new nation would be elevated to the aristocracy: twelve square miles would earn one a dukedom; smaller areas would earn lower ranks. The scheme was heavily advertised in France, Italy, Belgium and Germany. Plans were published of a grand city with fine buildings and spacious boulevards. People were encouraged to part with their hard-won capital and embark on a new life in the idyllic South Seas. European governments sought to discourage investors and to obstruct the scheme’s sponsor, but to little avail. Small investors almost stampeded to get on board.

Despite the best efforts of dissuading European governments, three shiploads of colonists departed for La Nouvelle France: SS Chandernagore, carrying 82 predominantly male colonists, left Flushing (Belgium) in September 1879; the steamer India, with 340 colonists which included women and children, left Barcelona (Spain) in July 1880; and the steamer Neu Bretagne, with 140 colonists, left Barcelona in April 1881. Other vessels were acquired by de Rays and used to support the adventure in minor ways, but only the three named above carried colonists. One of the support vessels was the small steamer Genil, which played a significant part in the dramas that followed.

It will be noted that the three passenger ships’ departure dates were separated by nine or ten months, and consequently their arrival dates in New Ireland were similarly staggered. Each expedition failed, and did so comprehensively. By the time India arrived, surviving colonists from Chandernagore had all left; and by the time Neu Bretagne arrived, the India people had left too. Eventually the colony was abandoned in February 1882. Many of the survivors of the expeditions eventually made their homes in Australia.

The de Rays colonisation adventure, from the first departure from Europe until the last departure from Port Breton, lasted only 2½ years. The hardships endured by the colonists are described in general by Niau, and though her book omits a full listing of all deaths, the ones she mentions are harrowing enough. Before the Chandernagore even reached Port Breton, a call was made at the Laughlan Islands (in what is now Milne Bay Province). Thirteen colonists, perhaps driven by conditions on board or by doubts about the way the colonisation was being managed, left the expedition there, intending to become copra traders; five died, and the remainder were rescued, near death, by HMS Conflict months later and taken to Queensland.

SS Chandernagore

The first colonists, in Chandernagore, reached Port Breton in January 1880. Instead of the broad boulevards and fine buildings they had expected, the colonists found nothing but rugged real estate clothed in rain forest to the water’s edge. Prospects for agriculture in the terrain were assessed as poor. Another site was tried, at Liki Liki, several hours’ walk away; the more level ground there seemed to offer better prospects, but proved too swampy and saline to be productive. Eventually the colonists settled at Irish Cove, north of the original settlement. Some desultory work saw a bunkhouse erected from prefabricated material, and some gardens started.

By April 1880, the fledgling colony was in such privation for want of nourishment, medicine and shelter that the colonists begged missionaries at the Wesleyan mission at Port Hunter in the Duke of York Islands for assistance. For a time, virtually all the colonists were cared for at the mission; seven, too far gone to survive, died after they arrived there. Later, more supplies arrived, and the survivors returned to the colony for a time. Six Italians stole a canoe and escaped. They reached Buka, where they were made captive; five were eaten before the sixth was fortuitously found and rescued by the Genil which happened to be passing. By September 1880, despite the additional supplies, the number of colonists had dwindled to 30 or 35; expedition managers evacuated them to Sydney.

SS India

The India, according to Niau, had a tragic voyage out: about 100 colonists died en route. The ship arrived at Port Breton in late October 1880, and found a miserable deserted camp. The colonists – predominantly Italian, with many women and children – at first showed energy in erecting buildings and planting crops, but they gradually lost heart. Within two months, they were in acute distress. There was illness, medicines were short; more deaths occurred. Local traders and missionaries helped all they could, but their resources were not infinite. By the end of February 1881 the situation was desperate. Nearly all the surviving members of the second expedition boarded the India again and headed south. They reached Noumea, and the French authorities refused to let the unseaworthy vessel leave port again. Word reached Sydney of the colonists’ plight, and the NSW Premier Sir Henry Parkes was moved to send the steamer James Patterson to collect them and bring them to Sydney – with costs being defrayed by the sale in Noumea of the India. The party arrived in Sydney on 7 April 1881. A newspaper report the next day listed 46 deaths en route – two after arrival in Sydney. The day the India’s party reached Sydney, ironically, was the same day the third load of 150 colonists sailed in the Neu Bretagne from Barcelona.

Interlude: The massacre of Mioko

Although the settlement at Port Breton was effectively deserted after the India left, one element of the expedition remained in the area: the steamer Genil. The vessel was under the command of the eccentric Captain Rabardy. Since the ship was equipped with a Gatling heavy machine gun and copious small arms, Rabardy was prevailed upon by traders in the Duke of York Islands to lend them tactical support. They were under considerable threat from a local tribe, and a demonstration of fire power would substantially increase the security of their position. In fairness to Rabardy and the traders, it must be said that the threat of attack was real and imminent. Nevertheless, the response was not balanced; indeed, it was excessive. By a clever stratagem, men, women and children were manoeuvered into a position from which their escape was hampered, and then massacred by Genil’s Gatling gun, supplemented by small arms fire. Niau records the number killed as ‘hundreds’, but she wasn’t there; certainly it must have been a large number. The whole story of the expeditions of de Rays is one of cynical greed and exploitation, but its lowest point is surely the Massacre of Mioko in April 1881.

SS Neu Bretagne

The Neu Bretagne arrived at Port Breton in August, knowing already that the previous two expeditions had ended in disaster. But even that knowledge left them ill-prepared for the sight of the chaotic mess that greeted them, with the foreshore littered with unused stores in front of the wreckage of a primitive camp. From arrival, they were short of food; the situation worsened day by day. In mid-September 1881, the Neu Bretagne sailed for Manila, carrying 55 sick colonists; 95 were left behind. The object of the voyage was to seek funds from de Rays with which to buy provisions and essential stores. The Genil remained in the vicinity of Port Breton together with an accommodation hulk that the de Rays enterprise had acquired. The remaining colonists – one third of whom were reported by missionaries in October as ‘too ill to walk’ – stayed on the two vessels.

In Manila, Neu Bretagne’s master, Captain Henry, received cabled assurances from de Rays that substantial funds would be sent at once. Henry ordered provisions and stores, and loaded them into the ship. The funds to pay for them never arrived. Spanish authorities placed the ship under arrest. Knowing the conditions at Port Breton, Henry took the ship out of port in the dead of night and escaped with his precious cargo; the ship reached Port Breton on 1 January 1882. Ten days later a pursuing Spanish gunboat arrived at Port Breton and arrested the ship again. The Spaniards gave what help they could to the colonists, and sailed on 20 January; they took with them the Neu Bretagne, a proportion of the sick, all the crew of the Genil who refused to stay on board any longer because of by-now-demented Captain Rabardy, and Captain Henry – who was to stand trial in Manila.

At Port Breton things progressed from bad to worse. All that remained were about 40 colonists, some useless stores, and the Genil with a mad captain, no fuel, and no crew. At the top, there was a three-way power struggle between the lawyer Chambaud (nominally the ‘Governor’ of Nouvelle France), Dr Badouin, and crazy Rabardy. The doctor recognised that the colony was finished, but the other two were determined to carry on. Only when a local missionary, Danks, threatened to compel a nearby British warship to intervene, was the matter settled. On 14 February 1882, Port Breton was abandoned and the colonists were moved temporarily to Mioko in the Duke of Yorks – where Rabardy died two days later. On 20 March 1882, the survivors sailed to Sydney in the Genil, arriving on 2 June – bringing to an end the disastrous de Rays adventure.

Post mortem

What was the death toll? Eight from the group who left the Chandernagore at the Laughlans were rescued by HMS Conflict and landed in Queensland. Of the remainder from Chandernagore, perhaps 35 were evacuated to Sydney. Two hundred from the India reached Sydney in the James Patterson. Fifty-five sick colonists made their escape to Manila in the Neu Bretagne; the remaining survivors of the Neu Bretagne party who came to Sydney numbered 40. A handful – perhaps 20 – of the colonists who survived the privations of Port Breton stayed in the area, working with local traders. Therefore, perhaps 358 survivors are accounted for. It is known that 562 colonists set out from Flushing and Barcelona, so probably something over 200 died of various causes – about half of them in the India’s disastrous outward passage. The above figures only include colonists, not ship’s crews or members of the expedition staff – from among whom several deaths are also recorded. And the quoted figure does not include the incalculable number of men, women and children massacred by Rabardy’s Gatling gun in April 1881.

Villains – and heroes

De Rays of course never set foot in the chaotic colony he tried to create. Having fled to Spain, he was extradited back to France and in 1883 was charged with ‘homicide through criminal imprudence’. The court heard of the extravagant lifestyle he had enjoyed, supported by his La Nouvelle France adventure – financed by those who suffered in it. He was convicted, and served six years in jail. On his release, he again embarked on entrepreneurial schemes, but they again led to failure and debt. The uncrowned king died on 29 July 1893.

Other significant villains in the saga include Rabardy and the lawyer Chambaud – both of whom reportedly used coercion and threats, including death threats – against the settlers to ensure their conformance with orders. Rabardy was also involved in deceptive land dealings with tribal and village chiefs, which put all members of the expedition in jeopardy.

There were heroes too, notably the doctor, Badouin, who treated his charges with humanity under difficult circumstances of great deprivation, and who ultimately stood up for them against the corrupt Chambaud and the dangerous Rabardy. And Badouin gave telling evidence at the trial of De Rays that clearly helped secure his conviction. The Methodist missionary, Danks, was another who provided succour to the starving and abandoned colonists, when they clearly were unable to support themselves. And more importantly, by supporting Dr Badouin in standing up to Rabardy and Chambaud at the end, he facilitated the escape of the last survivors from Neu Bretagne. Captain Henry deserves hero status too, for slipping illegally out of Manila knowing that lives depended on delivering the supplies that his ship carried. (Fortune smiled at his trial: he was acquitted, the Neu Bretagne became a local trading vessel around the Philippines, which he commanded.)

A colony is founded

The 200 expedition survivors from the India, who reached Sydney via Noumea in April 1881, made a considerable impact in the town. Initially, they received care and support from the colonial government and local residents, but the government made it clear that this largesse was not open-ended, and they were expected to find employment. Most of this group were Italian, and it included large families spanning generations; the natural desire of families not to be separated hindered employment options. Between 1882 and 1885, forty of the families took up land totalling about nine square miles near Woodburn on the Richmond River, in the north of the state. They called the settlement New Italy. As a commercial farming venture, it struggled and ultimately withered. Nevertheless, it remained home to several families who hung on until the last descendant left in the 1950s. Although New Italy survives today as a signposted tourist site, it harbours few relics of the disastrous expedition that led to its foundation.

New Italy was the only coherent settlement formed by La Nouvelle France survivors, many others of whom were absorbed into the general Australian community. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that the Australian population today numbers perhaps several hundred descendents of the survivors of the de Rays swindle – so those intrepid, trusting and optimistic souls found a new home after all.

A winner emerges

There was another unlikely winner out of the whole affair. The trading firm Farrell and Company, with partners Thomas and Emma Farrell, newly-established in the Duke of York Islands, was another source of support to the colonists, particularly at the end. Indeed, without the organisational flair of the Farrells, arrangements for the final departure of the Neu Bretagne survivors could have fallen apart. But Farrell & Company had the opportunist’s eye for the main chance: Port Breton was littered with considerable quantities of useful cargo, including agricultural implements and building materials, and a couple of vessels, that could be sold or put to use. So the Farrell’s prize for helping the colonists’ escape was to acquire title to everything that was left behind. It was an invaluable starting nest-egg in the circumstances.

The Farrells parted company soon after, for Thomas was interested in trading while Emma took the longer view and wanted to establish plantations before the expected declaration of sovereignty over the area by Germany. Emma’s timing was fortuitous; she built a plantation empire in what is now the Gazelle, the Bainings and the Vitu Islands, and eventually sold out profitably to the German entrepreneur and adventurer Rudolph Wahlen, and secured her place in history as Queen Emma. Hers is another, and better-known, story.