- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Lindsey Shaw

Lindsey Shaw is a former Senior Curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Committee Member of the Naval Historical Society and Member of the Board of Directors of the Historic Naval Ships Association

This October saw Sydney abuzz with tall ships, flypasts and warships as the Royal Australian Navy celebrated in style a milestone in its history. A century ago the first Australian fleet unit was loudly and emphatically welcomed into Sydney as a sign of our nationhood and an indication of a strong future as an independent member of the Empire. But the formation of the Australian navy didn’t happen overnight and its creation sparked much debate – both for and against the concept.

With the Royal Navy providing Australia’s naval defence – the Australia Station was established in 1859 – many believed that Britain’s defence of its oceanic trade and colonial expansion was more than adequate. It was Australia’s patriotic duty to support the British homeland and that support was borne out in its participation in Crimea, South Africa and China well before Federation in 1901. It was the foresight of men like Sir William Rooke Creswell who started and maintained the discussions and debates. He argued for adequate Australian naval forces to support the Royal Navy ships on the Australia Station as early as 1886. Twenty years later he recommended the formation of an Australian torpedo boat and destroyer force – a proposal adopted by Prime Minister Deakin – locally manned for coastal and trade route defence.

The Australasian Naval Defence Act of 1887 had meant that Australia and New Zealand paid subsidies for maritime protection in the form of the Auxiliary Squadron. But as Federation came closer many believed defence of the country should be one of the powers given to the central government; preceded by a reduction in the dependence on Britain to provide a defensive force. There was a big push to opt for a locally manned and maintained naval fleet but also continuing the strong Imperial ties.

The concept of a specifically Australian fleet of warships culminated in the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909 when it was decided that one battle cruiser, three second-class cruisers, six destroyers and three submarines would be constructed to form an Australian fleet unit. With German and Japanese naval power on a rapid rise and the display of naval strength (and intelligence gathering) by the United States’ Great White Fleet the previous year, Australia’s naval planners steadily established a firm naval policy for a unit that would be ready to serve the nation’s and Empire’s needs and that had the proper administration and systems to support it. The Asia-Pacific region of the 1890s and 1900s was constantly changing. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 was one of the unsettling actions in the region, one that brought Japanese, Russian and German influence to bear. If Britain was dealing with these concerns of competing European powers in the Pacific, where did the defence of Australia stand? The Japanese naval victory over Russia in the Battle of Tsushima in 1905 was cause for concern when the Admiralty recalled five battleships from the China Station to home waters, leaving Australia feeling abandoned.

Debate raged not only in political circles but through the newspapers too. The Minister for Works, Mr E.W. O’Sullivan (as reported in the Sydney Morning Herald, January 1900) said he ‘…hoped one day to see an Australian navy, which would do as well as their soldiers and maintain their natural heritage – the supremacy of the Pacific Ocean.’ On the other side however there were men like Lt-Col G.H. Newman (Ret’d) who advocated a Naval Corps and that ‘Britain build the ships and man them’. He also recommended that Australia should ‘…offer special inducements to time-expired seamen of her Majesty’s navy to settle here…and form a sort of Royal Naval Reserve’. This, he argued, would be ‘…a far more workable scheme than the creation of an Australian navy.’1

When Creswell was interviewed in 1900 and spoke of his plans for an Australian naval reserve, the amalgamation of existing colonial naval establishments and ships and the provision of effective warships by the British Admiralty, he was roundly criticised by The Times. Their editorial reported that ‘…the force thus raised’ would be made up of ‘…amateurs, half-trained volunteers, and longshoremen’. An insult indeed, considering the fighting force that was produced a little over a decade later! Commandant F. Tickell supported Creswell and others when questions were asked about the purpose of a naval fleet. ‘…Australia should be in a position, not only to protect her own coastline, but also her commerce against possible attack’.2

Year after year ideas and plans were put forward as to the state of Australia’s naval defence in the pre and post-Federation years. More and more agreed that the country needed its own force as the Royal Navy was realistically just too far away in case of emergency and would not be Australia’s first line of naval defence, although as Nicholls says, ‘…there never was a threat of any magnitude facing any part of the Australian mainland’.3 But there were still those who believed that it would be too expensive for the young nation to produce and maintain a naval fleet of its own, especially given the economic downturn of the 1890s. Samuel P Gregan, late Royal Artillery, summed up the feelings of many, ‘…therefore let Australians stick to that grand old block from which we sprang, and Great Britain and Ireland, in spite of allcomers, will see us through.’4

The purpose of such a naval unit would be to defend Australia and to support the rest of the British Empire. At Federation the various ageing naval ships from the colonial state governments were known collectively as the Commonwealth Naval Forces and they were adequate for coastal defence but fell short of being a naval force with which to be reckoned. A Royal Navy squadron was stationed in Sydney for the protection of both Australia and New Zealand – with £200,000 being annually contributed towards the maintenance of this fleet. But at any time this British squadron could be removed leaving Australia without naval protection. It was time for Australia to have its own modern navy.

‘First-born of the Commonwealth navy, I name you the Parramatta. God bless you, and those who sail in you. May you uphold the glorious traditions of the British navy in the dominions overseas’. With these christening words the destroyer HMAS Parramatta was successfully launched by Mrs Asquith, wife of the Prime Minister of England at Govan on the River Clyde on 10 February 1910. Over the following three years Parramatta was followed in succession by the destroyers HMA Ships Yarra, Warrego, Torrens, Swan and Derwent; the battleship HMAS Australia; the light cruisers HMA Ships Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane; and the two submarines with the latest technology, HMAS/M AE1 and AE2.

During World War I Australia’s naval fighting capabilities were proven but support of the fleet was just as paramount and the Naval Board made sure logistic support was there too through victualling and naval stores, engineering, shipbuilding and maintenance; hospital ships and troop transports were also provided. A strong desire was to have as many Australians as possible on these Australian warships. However it was realised that men of the British navy would be needed in training and operating roles in the early years of the Navy’s development. A training school was established at the naval depot in Williamstown; Tingira was commissioned as a boys’ training ship. This new navy replicated the Royal Navy in hierarchy, organisation and structure, but went on to create its own style. Naval historian Nicholas Lambert argues that ‘…the Australian fleet unit was effectively the test bed for the Royal Navy’s newest warship types, as well as the latest (albeit controversial) tactical ideas and doctrine’.5 Exciting opportunities awaited those who signed for the Australian fleet unit and it was ‘so popular that there was a superabundance of candidates for the privilege of entering it’.6

The official arrival of the Australian fleet unit into Sydney on 4 October 1913 was received enthusiastically by Sydneysiders and visitors alike. Thousands lined every vantage point along the shores of the harbour and boats of all kinds were on hand to watch as the fleet entered in formation with the battlecruiser Australia leading. A deafening salute from the 12-inch guns of Australia reverberated up and down Port Jackson. The stately procession was loudly and enthusiastically cheered on as it made its way to Garden Island and Farm Cove where it was greeted by the Governor and Premier of New South Wales and a roaring crowd of citizens.

Schoolchildren played their part in the great event too with a massed schools display at the Sydney Cricket Ground, the highlight of which was a living shield within a map of Australia formed by 8,000 boys and girls. Special tours of the flagship Australia were a highlight for some 3,000 children. A formal banquet was held to welcome the new fleet and its officers and the Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, and Leader of the Opposition, Joseph Cook, both delivered speeches punctuated by cheers from the audience. The Sydney Morning Herald reported, ‘…they were at one in their assertion that in the hour of danger the Australian unit will be found where it can do the greatest service’. And indeed that is what happened a mere 10 months later when Australia declared its support of Great Britain and the country went to war against Germany.

Whilst recruiting began in earnest for troops and lighthorsemen, the RAN was quick off the mark – sailing north with the Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) to take German New Guinea in a matter of weeks, and routing Admiral Graf Spee’s German East Asiatic Squadron. The first Australian casualty of the war was a sailor – Able Seaman William Williams, fatally wounded on 11 September 1914. The first naval vessel lost was the submarine AE1 which went out on patrol off New Britain on 14 September 1914 but did not return. Her final resting place has never been located and so the exact cause of her loss remains unknown. With the upcoming 2014 – 2018 commemorations of World War I, it may be that this mystery will at last be solved.

Australia’s navy – our ‘Navy Blue ANZACS’ – served across the globe in this ‘war to end all wars’. From the Pacific and Indian Oceans to the Atlantic, the North Sea to the Mediterranean, the RAN patrolled, escorted, fought and bombarded as part of the British Grand Fleet. Significantly HMAS Sydney soundly defeated the German raider SMS Emden in a fierce battle off the Cocos Islands in November 1914 and AE2 was the first Allied submarine to successfully penetrate the Dardanelles Straits, disrupting Turkish and German shipping. The Royal Australian Naval Bridging Train (RANBT) was the first in and the last out of Gallipoli – building pontoons, bridges and jetties for the landings and evacuations of the troops. By war’s end the Royal Australian Navy had lost 15 officers and 156 sailors, including the entire complement of the submarine AE1.

One hundred years of cooperation and interoperability between Australia and other world navies is a significant milestone to have reached. The words of Acting Prime Minister William Hughes in welcoming HMA Ships Parramatta and Yarra to Melbourne in 1910 are as relevant today as they were then: ‘We, as a nation, realised that to achieve our destiny, to be left free to foster the arts of peace, we must be prepared for war. We must not shut our eyes, and be blind to the facts of life. We had to face the world as it was, to be ready to protect that which we held dear’.7

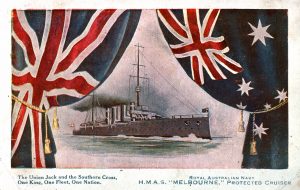

One King, One Fleet, One Nation? Certainly from the British Admiralty’s viewpoint this would be a true statement when the fleet unit arrived in Australia a century ago. A single Imperial Navy under Britain’s control was the ideal for maintaining control of the seas across the Empire. However it was local needs, modern 20th century thinking and an Australian identity that slowly shaped the Royal Australian Navy in its decades of growth after World War I. Team Navy of the 21st century has a sound foundation and a proud history on which to go forward.

1 The Brisbane Courier 4 April 1900

2 Sydney Morning Herald 20 September 1900

3 Bob Nicholls, ‘Colonial naval forces before Federation’, in Southern Trident – strategy, history and the rise of Australian Naval Power, Allen & Unwin, 2001

4 Sydney Morning Herald 2 January 1907

5 Nicholas Lambert, ‘Sir John Fisher, the fleet unit concept, and the creation of the Royal Australian Navy’, in Southern Trident – strategy, history and the rise of Australian Naval Power, Allen & Unwin, 2001

6 Admiral Sir George King-Hall, 1912

7 The Argus 12 December 1910

Bibliography

The Australian Centenary History of Defence, Volume III, The Royal Australian Navy, David Stevens, editor, Oxford University Press, 2001

The Commonwealth Navies: 100 Years of Cooperation, Kathryn Young and Rhett Mitchell, editors, Sea Power Centre – Australia, 2012

Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No 17, Australian Naval Personalities – Lives from the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Gregory P Gilbert, Sea Power Centre – Australia, 2006

Southern Trident – strategy, history and the rise of Australian Naval Power, David Stevens and John Reeve, editors, Allen & Unwin, 2001