- Author

- Kingsley Perry

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Sydney III, HMAS Yarra III

- Publication

- June 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Kingsley Perry

Commander Kingsley Perry (Retd) was a midshipman under training in HMAS Sydney in 1963 when a tragic boating accident occurred in the Whitsunday Group, resulting in the loss of five young lives. Kingsley was the coxswain of the third whaler identified in this narrative.

In the early 1960s, immediately after their graduation from the RAN College, HMAS Creswell at Jervis Bay, midshipmen in the Royal Australian Navy spent 12 months at sea before proceeding to the United Kingdom for further training. A class of 26 midshipmen graduated on 19 July 1963.They were posted in groups around a number of ships including HMAS Sydney, a Majestic class aircraft carrier that was being used as a training ship (and later as a fast troop transport during the Vietnam war). The group in Sydney was joined by three other junior officers who were undergoing similar training following entry under different schemes.

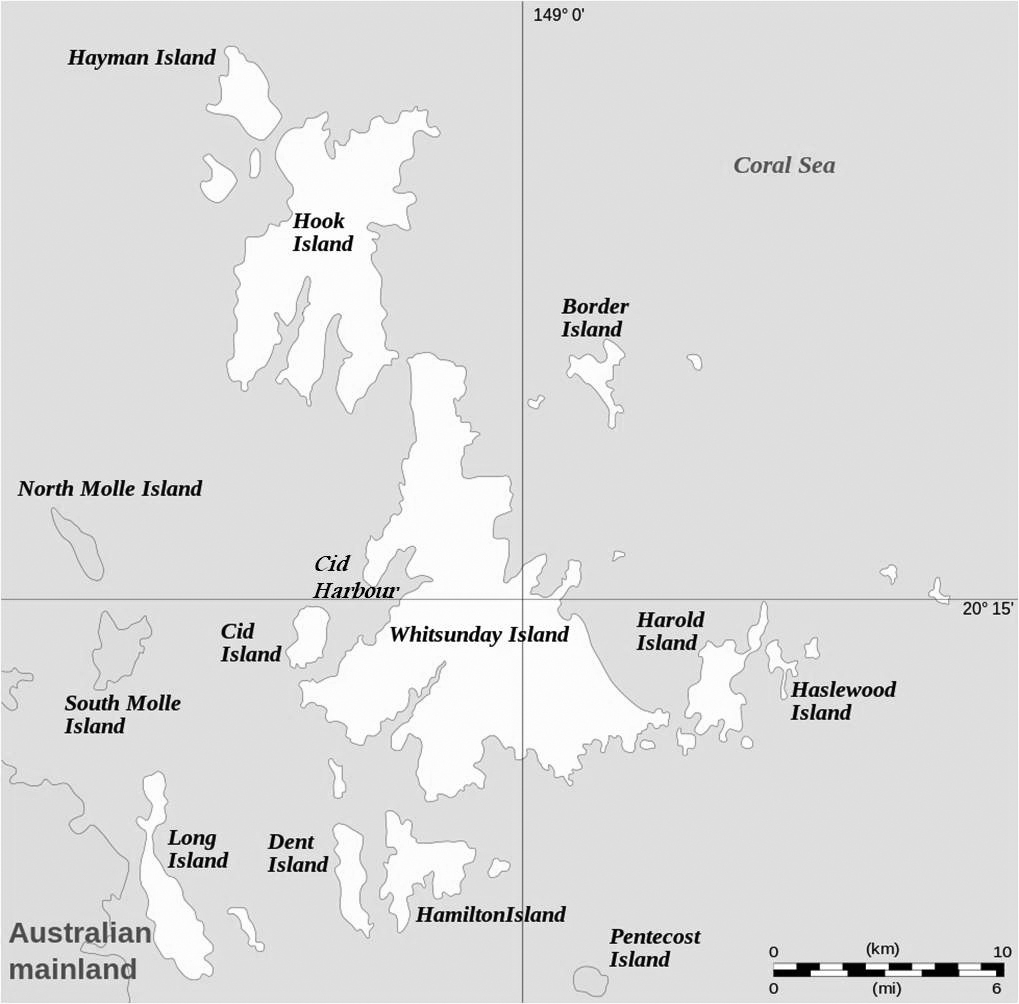

In mid October 1963, Sydney, in company with HMAS Anzac, was in the Whitsunday Group of islands off the Queensland coast. Anzac was a Battle class destroyer, then used as a training ship. They were anchored at Cid Harbour, between Cid Island and the west coast of Whitsunday Island and to the south of Hook Island. The weather and conditions at Cid Harbour, in the lee of Whitsunday Island, were idyllic.

The Incident

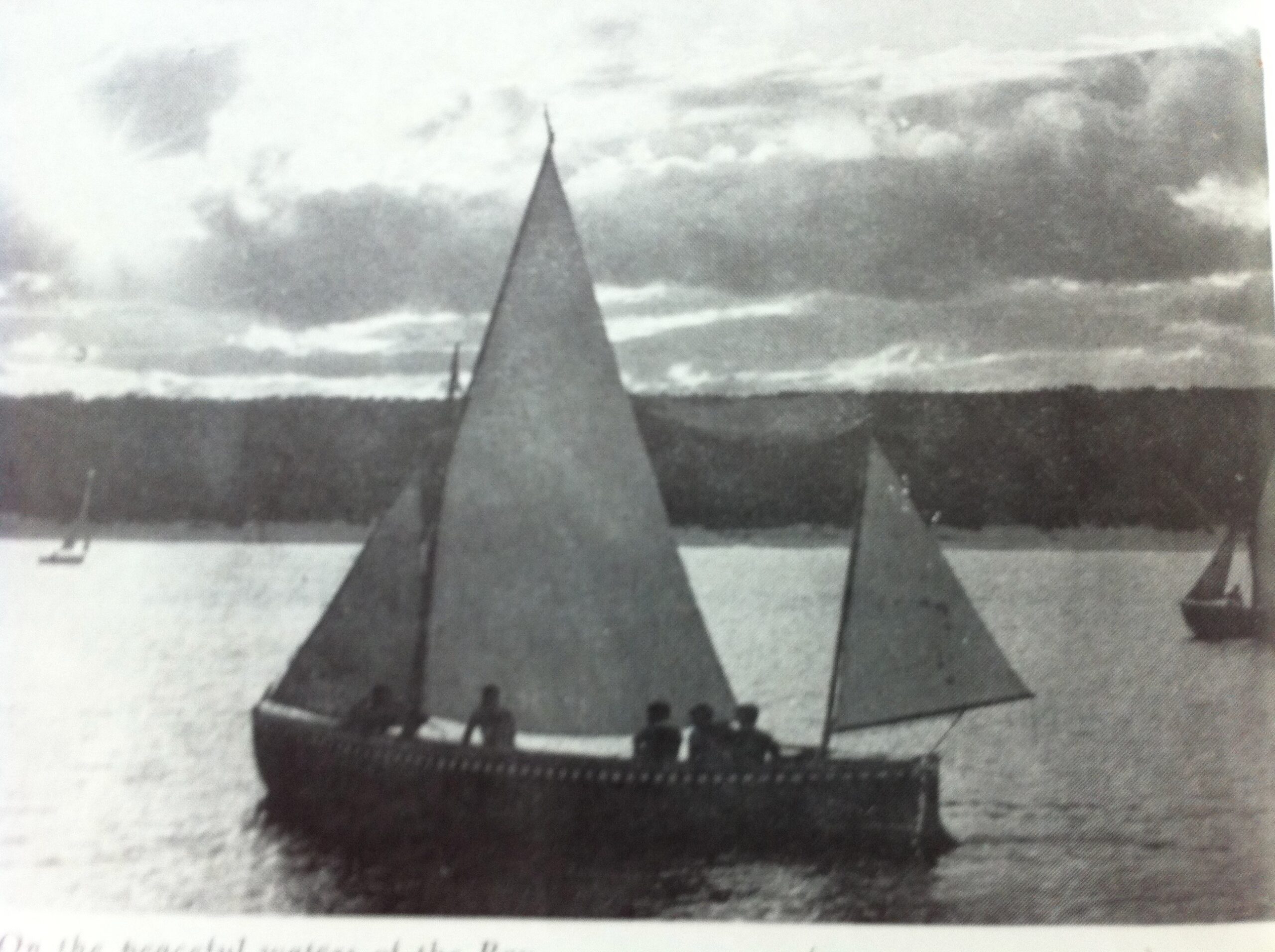

As Sydney was to be in the region for a few days, it was decided that the junior officers under training should take part in sailing exercises in the ship’s 27-foot whalers. Known as Montagu (Rig) Whalers, these were clinker-built boats, twin-masted and sturdy, but inefficient sailing boats. They had been in naval service for many decades. Four groups of four or five officers were to sail on successive days from Sydney around Hook Island and return, a journey of about 35 nautical miles. Each group was to plan its own journey. There would be a Captain’s prize (undisclosed) to the crew of the fastest boat.

The first group set sail on Monday 14 October. They planned to circumnavigate Hook Island in an anticlockwise direction. They encountered high winds and rough seas, but nearly completed the task. At about 1800 they were towed back to Sydney by a motor boat from Sydney (the crew of which had been fishing) from near the south-western corner of Hook Island as they were unable to make any further headway against the tidal stream.

On the following day the second group decided on a clockwise circumnavigation, but because of adverse tidal stream and extreme weather conditions they were unable to traverse the northern side of Hook Island. They headed back for safety but ran aground on Black Island, a small island about one mile south of Hayman Island off the north-western corner of Hook Island. They were rescued by a passing fishing boat and towed to Hayman Island. They made contact with Sydney, using Hayman Island’s radio transceiver. They spent a comfortable night on the island, and the following morning, with some help from a couple of junior officers from Anzac which had been dispatched to assist them and some additional safety equipment provided by Anzac, they retraced their course to Sydney at Cid Harbour with some towing help from another civilian boat.

The third group left early on 16 October, planning to circumnavigate in a clockwise direction. All went well until they found they could not overcome the adverse tidal stream and wind conditions around Pinnacle Point at the north-eastern corner of Hook Island. They went ashore at Butterfly Bay on the northern side of the island and set up camp there as best they could. They were unable to make any radio contact with Sydney. At 0500 the following morning they set off again, with shortened sail. This time, despite high wind and high seas, they were able to get around Pinnacle Point, reach the east coast of Hook Island and head south towards the ship. The conditions moderated slightly, but there was still a strong headwind from the south-east.

About half-way down the island they met the fourth and final group which had left Sydney at 0500 on Thursday, 17 October, heading for an opposite, anticlockwise circumnavigation. It had a crew of five, a sub lieutenant and four midshipmen. Pleasantries were exchanged and warnings were given of the rough and windy conditions ahead. The fourth whaler then resumed its ill-fated journey northward, at good speed under full sail and with an extra foresail. At that time the crew was in good spirits. They were not wearing life jackets.

The third whaler continued its journey southward, but was met a short time later by a motor boat from Sydney that had been sent out to find them, and was towed back to the ship. So far none of the three groups had completed its circumnavigation without assistance. The fourth was destined not to complete its circumnavigation at all.

On board Sydney it was thought that the fourth whaler, circumnavigating in the same direction as the first, should be sighted by about 1800. There was no such sighting, and at 1900 a 32-foot motor cutter was dispatched with a crew of three to check the west side of Hook Island. It returned at about 2200 without finding any trace of the whaler. The motor cutter was then sent with a new crew to search further. The crews for these two trips included midshipmen who had just completed their circumnavigation that morning.

The crew of this second motor cutter trip also found nothing, and so landed at Hayman Island at about 0200 the following morning to make enquiries. They were told that the day before a guest had reported that he had seen what appeared to be an upturned boat with three people clinging to it about a mile north of Hayman Island. Attempts had been made by the island’s manager to contact Sydney and Anzac by radio but the message did not get through. A boat had also left from Hayman Island to investigate, but it broke down. No further action was taken. The crew of the motor cutter was not able to contact Sydney by radio to relay this very significant news of the sighting of what appeared to be an upturned boat, and so made haste to return to the ship, arriving at about 0500. The gravity of the situation at last became very apparent.

Search and rescue operations commenced immediately. Sydney and Anzac weighed anchor, RAAF Neptunes and other aircraft were mobilised, and search-and-rescue launch Air Sprite and naval aircraft joined in. HMAS Yarra arrived soon after. Army personnel and civilians joined the search ashore.

At night on Sunday, 20 October, as Anzac was returning to the search area from a refueling visit to Townsville, a sailor reported seeing what he thought was a submerged dinghy passing close by the ship. A search was commenced, but it was not until about midday the day after that the submerged whaler was found, about 64 miles north-west of Hayman Island. The torn mainsail and boom were also found later.

There were two bodies inside the submerged whaler, Midshipman D.J. Sanders and Midshipman G.J. Pierce. It had been dismasted and the stretcher boards (foot supports for rowing) and oars were missing. There was no trace of the three other members of the crew, Sub Lieutenant N.J. Longstaff RANR, Midshipman P.G. Mulvany and Midshipman B.H. Mayger. Their bodies were never found.

The Aftermath

A naval board of inquiry was immediately convened by the Flag Officer Commanding Australian Fleet. It assembled in Sydney which remained at sea in the region of Whitsunday Island. The proceedings were open to the public (although access must have proved difficult) and received significant press coverage. The board took evidence from witnesses including some of the midshipmen involved in earlier sailing groups and the rescue operations. It submitted its report to the Flag Officer. Meanwhile, the searching at sea and ashore continued for a fortnight, to no avail except for a few pieces of flotsam.

A decision was made that three of Sydney’s officers should face court-martial. The courts-martial were to take place in Fleet Headquarters in Sydney on 26, 27 and 28 November 1963. The officers to face charges were the Training Officer (a lieutenant commander who was also the Navigating Officer), the Executive Officer (a commander, who had acted as the Commanding Officer during the Commanding Officer’s absence for a few hours on the afternoon of 17 October) and the Commanding Officer (a captain). Each faced two charges relating to alleged deficiencies in precautionary measures taken and instigating the search for the missing whaler and its crew.

The Training Officer and the Executive Officer were found not guilty. The Commanding Officer, the last to be tried, was found not guilty of one of the two charges against him, but was found guilty of neglect of duty in failing to keep himself informed of the progress of the whaler. The court recommended he be reprimanded.

A fortnight later, on 13 December 1963, the Minister for the Navy announced that the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board had reviewed the proceedings of the trial by court-martial of the Commanding Officer and determined that the finding of guilty was not supported by the evidence and that the finding should be quashed.

Thus, less than two months after it occurred, this avoidable tragedy in which five young officers lost their lives was brought to a conclusion, and without any finding of accountability or any repercussions. It seems nothing was learned. Whatever interest remained was effectively extinguished only two months later when the Navy was struck by an even worse disaster.

On 10 February 1964 the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne collided with the Daring class destroyer HMAS Voyager off Jervis Bay, south of Sydney. Voyager sank with the loss of 82 lives. Four of the midshipmen who had been serving in Sydney in October 1963 were among those lost in Voyager. The Voyager disaster was the subject of two Royal Commissions, extensive parliamentary and press scrutiny and a number of books. Accountability was an issue and the repercussions were far-reaching. By its magnitude and timing it eclipsed the Whitsunday whaler disaster, which sadly was relegated to relative historical obscurity.

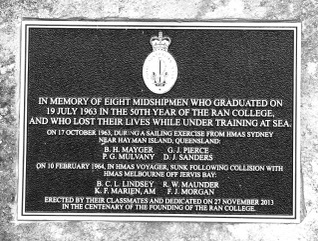

A memorial to the eight midshipmen who lost their lives within seven months of their graduation in July 1963 was dedicated at the RAN College on 27 November 2013, in the centenary of the founding of the College and the jubilee of their graduation (they also being the jubilee graduating year of the College).