- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Mary Mennis

This interesting article is by an author who lived many years in New Guinea studying anthropology and almost by accident became expert in an older style of local boatbuilding techniques and instrumental in reviving the art. It helps demonstrates an indigenous sophistication and use of technology in boatbuilding and a knowledge of the marine environment, developed over many centuries. A better understanding of traditional maritime cultures amongst our neighbours may benefit such aid projects as the Pacific Patrol Boat Program.

The Motu and the Bel people both belong to Austronesian language groups and have common origins but had no contact with each other for over a thousand years. The Motu people are on the south-coast of Papua New Guinea and the Bel people live on the north-coast, separated by high mountain ranges and hundreds of kilometres of twisting coast. Despite this, they had a lot in common in their way of life: they overcame food shortages by making earthenware pots which they traded for food from other areas and they both built large canoes to carry these cargoes of pots. However, the form of these canoes was dependent on their function and as a result they developed quite different types of canoes. The technical knowledge that was applied in these canoes was the highest technology reached in the traditional societies who built them.

The Motu people and the lagatoi

For centuries the Motu people near Port Moresby built large lagatoi with their distinctive crab-claw sails. One of these lagatoi featured in early stamps of British New Guinea. Sir Hubert Murray had a similar photograph in his book, (Murray, 1925: p235), showing the crows-nest platform midway up the sails where a watchman kept an eye on the water and the passage ahead. It is similar to the crows-nest lookout on Western style sailing vessels.

The Motuans could be at sea for many days and nights and travelled in fleets for protection. They used an ingenious instrument called kino kino with a long pennant at one end which was lashed to the rigging with its tip aligned with Venus and which helped them stay on course (Lewis, 1972: p95). They sailed their lagatoi to the Gulf of Papua where they exchanged their clay pots for sago which was needed during the hungry times of the year. While they waited for the winds to change, the men busied themselves adding more hulls to the lagatoi to cope with the extra weight of the sago. This meant that the journey home could be more hazardous than before. There was ritual and magic to protect these craft against evil spirits at every stage of construction and while at sea.

Building the lagatoi in traditional times

Tools were all made from natural materials: wood, stone, vines, obsidian, shells and bone. Sharpened stones were tied with vines to wooden hafts to make their stone axes. It would have been an arduous task cutting large trees down with them. Adzes were used to hollow the hulls which were the base of the lagatoi. Because of the number of hulls used, the lagatoi has been described as more like a raft than a canoe. The hulls were lashed together through holes along the top. If one hull sat higher in the water, it was filled with sea water to bring it down level with the others. The vine lashings connecting the hulls to each other were also tied on to crossbeams laid over them. These beams were the basis of the deck with more bamboo poles now laid on top parallel to the hulls.

On top of this platform, two closed-in shelters were built to provide accommodation and storage. In themselves they would have had too much wind resistance but they were protected from the elements by side fences which cocooned the lagatoi against strong winds. Masts were made from whole logs including the roots which were trimmed to fit the space on the deck and kept in place with a square of more logs. The crab-claw sails, which are the most outstanding feature of the lagatoi, were made on the beach where the outline was marked with poles and bent bamboo sticks tied together. Mats were cut to fit the outline and sewn in place to form the crab-claw pattern.

The lalong and balangut of the Bel people on the North Coast

The Bel people also built large canoes and traded their pots along the coast. The length of the hull determined whether it should have one or two masts. The single mast one was the lalong and the two masts was the balangut. Magic rituals were used at every part of building the canoes and when they were at sea. The men believed that the tree from which the hull was made was protected by bush spirits so that when it was put in the sea, the sea spirits were bound to be angry and attack it and so a secret language was used to confuse them. Once the hull had been shaped, it took a month or so to add the superstructure using stone axes, wooden hammers, and pigs’ bone tools. There were feasts and singsings when a canoe was finished.

Building the canoes

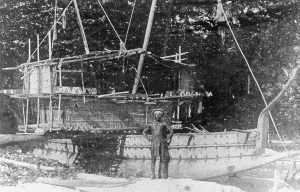

Hulls up to fifteen metres long were purchased from other villages and paid for by pots, lined up the length of the canoe. Each canoe had only one hull and a single outrigger. Along the top of the hull, holes were cut to which were tied L-shaped supports, the tilau. Planks were cut from long logs and attached to the tilau supports providing the basis for the pot-cage and shelter. All holes were caulked with a putty made from the dim tree.

The single outrigger float was connected to the hull by two booms. The dom or connectives between the booms and the outrigger were under the tremendous strain and were put in sideways so they would not be dislodged easily. The base of the platform was formed by laying poles laterally over the booms. On top of these, other poles were laid parallel to the boom, to form the lower platform. Bamboo flooring was then laid between them and carefully sewn in place with a cross-stitch done with a strong vine. This platform formed the base of the pot-cage which extended over to the outrigger to balance the canoe and to act as a brace against the wind while at sea.

The mast was made from a log with its roots removed and held in place on the floor of the hull in a diagonal shaped lump of wood, with a round hole in the middle. It was also braced by the two platforms and the shelter. This contrasted with the Motuan mast which was installed roots and all.

The roof on the lalong canoe is one of its remarkable features. At first glance it seems that there is a house on the canoe. In fact, this is how Miklouho Maclay, the Russian scientist, described them when he first saw these canoes in 1871 (Sentinella, 1975: p40). On closer observation, it is really only a shelter open on both sides. If the sides were blocked in as in a house there would be too much wind resistance and the canoe would overbalance in heavy seas. The Motu sailors overcame this problem with the fences built alongside their closed shelters protecting the lagatoi from the wind.

The outline of the lalong sail was marked on the sand.Two poles, five metres long were laid on the ground three metres apart. The weaving was done using garabud leaves (pandanus) through the warp. When hoisting the sail up, a halyard was looped over the mast prong. According to Haddon and Hornell, this is a more advanced style of sail than those used on other canoes in the Pacific where there is no mast and the oblong sail is supported by spars only. (1991, Vol iii: p10). These sails enabled the canoe to be sailed with the trade winds.

The lalong and balangut were built as trading canoes to carry hundreds of cooking pots in the pot cages which straddled the outrigger. The Bel men also travelled in fleets for protection. The totems on top of each mast identified the canoe and notified their friends on the Rai Coast of their arrival.

Comparing the lagatoi and the lalong

The lagatoi graced Port Moresby Harbour for centuries and were the admiration of the early British and Australian explorers. The lalong and balangut on the north-coast were also admired by the early Russian and German explorers. Sadly both ceased being produced within seventy years of these first contacts. It is not known what the local people thought of the first naval vessels which towered over their canoes, but they had achieved an amazing feat making their lagatoi and lalong out of the materials, tools and knowledge at their disposal. They had developed quite different styles, first apparent in the design of the sails – the crab claw sail of the lagatoi contrasting with the large rectangular mat sails of the Bel canoes.

The function of each canoe dictated its form or shape. The lagatoi was really a large barge or raft made of many hulls lashed together for stability. The Bel canoe on the other hand had one hull and a single outrigger with a pot cage built across the main part of the canoe. Both canoes had compartments for their precious cargo and shelters for the traders on their long voyages.

Furthermore the nature of their trading voyages also dictated their form. The lagatoi could only be moored and were not readily pulled up on beaches. The sailors had only one destination in the Gulf where the lagatoi were moored in the river alongside their trading village. The Bel sailors, on the other hand, called into numerous villages along the coast, exchanging their pots for food, weapons, and many other items. Their canoes could easily be pulled up on the beach at each village, safe from the crashing waves.

These large canoes are no longer built for trading but there is a growing interest in them as cultural objects in themselves. In 2013, a balangut was built for Independence Day celebrations in Madang. There were great festivities for this cultural item from their past. Each year, the Hiri Moale Festival is held in Port Moresby and lagatoiare re-built in recognition of the ancestors who once went Sailing for Survival.

In 1978, the author recorded the construction of a lalong, the first to be built for forty years at a time when there were only four old canoe builders left. Their knowledge was thus stored for future generations and was used by the next generation to build a balangut in 2013. In 1995, the author was one of a team to study the building of two lagatoi on Queensland’s Magnetic Island for the fifty year celebrations since the end of WWII. Both were memorable and informative occasions. [For further information and references see Sailing for Survival, 2014. This volume is available on the internet as an E-book.]

Bibliography

Haddon, A.C. and Hornell, J.1991. Canoes of Oceania. Second Printing. Vols i, ii, and iii. Bishop Museum Press, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Lewis, D., 1972. We the Navigators. ANU Canberra.

Mennis, M.R., 2011. Mariners of Madang and Austronesian Canoes of Astrolabe Bay. Research report Series Volume 9, University of Queensland.

Mennis, M.R., 2014. Sailing for Survival. Department of Anthropology and Archaeology. University of Otago.

Murray, H., 1925. Papua of Today. Westminster, London.

Sentinella, C.L., 1975. New Guinea Diaries 1871-1883.Miklouho Maclay. Kristen Pres, Madang.