- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1, History - WW2, History - Between the wars

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2015 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

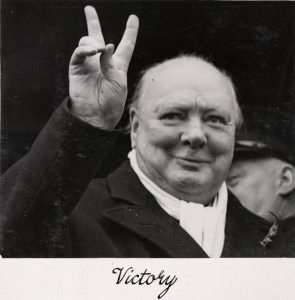

As fifty years have now elapsed since his passing this article may serve as a small tribute to the memory of this great wartime leader.

A meteoritic rise upon the world stage

Winston Spencer Churchill was perhaps the foremost of all characters taking the world stage during the turbulent period between the decline of Victorian empires and the post world war rise of social democracies. His influence on world affairs was profound and this extended to both naval enterprises and Australian politics. He was a leading character worthy of Shakespearean tragedy, which Hamlet expresses as: He was a man, take him for all in all: I shall not look upon his like again.

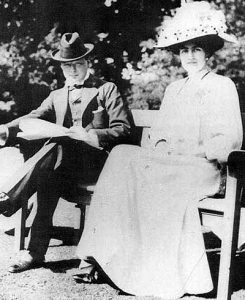

Winston Churchill was born on 30 November 1874. He excelled as a junior army officer, journalist and politician. In 1908 when aged 34 he married Clementine Hozier, a granddaughter of the Earl of Airlie, who was ten years his junior. As Churchill was short of money and the Hoziers were in similar circumstances this was an unusual match, but Clementine was bright and attractive and, being largely educated at a state grammar school, was worldlier than many of her contemporaries. Clementine’s younger brother William joined the Royal Navy and served as a Lieutenant during WWI. He resigned after the war and later committed suicide.

In 1905 when only 30 Churchill had his first taste of political power when he was made Under-Secretary for the Colonies (as the Colonial Office was also responsible for the Dominions, here he would have become acquainted with Australian issues). This was followed by a succession of promotions: 1908 President of the Board of Trade, 1910 Home Secretary and in October 1911 the prestigious position of First Lord of the Admiralty.

The latter came with prerequisites including an imposing residence at Admiralty House and unlimited access to the Admiralty steam yacht HMS Enchantress.This grand 3,470 ton vessel with a complement of 200 officers and men was to become Winston’s home away from home. Here he could find reasons to visit ships and establishments around the British Isles and take Mediterranean cruises with family and political friends. He also busied himself with the formation of the Naval Air Service and took flying lessons.

First Sea Lord

Winston threw himself into the affairs of Admiralty with relish which far exceeded an expected administrative role. He became increasing involved in operational issues. The Navy had been nurtured for a number of years by Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher who retired on 25 January 1910. His replacement, the robust Admiral of the Fleet Sir Arthur Wilson, VC soon clashed with the new First Lord resulting in the admiral’s premature retirement. He was replaced by someone Churchill thought trustworthy, Admiral Sir Francis Bridgeman. When Bridgeman objected to Churchill’s meddling in operational issues he too was forced to resign. His replacement was Admiral Prince Louis of Battenberg, well known to Churchill who considered him malleable. This was an unfortunate appointment as, with anti-German sentiment, the Prince was forced from office shortly after the declaration of war.

In the new era of instant (radio) communications decisions were able to made rapidly, with a greater need for continuous consultation between military and naval forces. The Army was supported by its general staff but the navy was suspicious of allowing decision to be made by relatively junior staff officers who were far removed from seagoing professionals. Churchill became a champion for the creation of a naval staff over which he could exercise control. The influence of Churchill, with his fine use of language more attuned to journalism than naval operations, can be seen in messages sent from the Admiralty to the Fleet and may in part have led to confusion in operational matters. Unfortunately, within the new naval staff there was no one capable of guiding the now self proclaimed ruler of the king’s navy.

The style of the ever-combative First Lord in communicating to the First Sea Lord (Prince Louis) with his desire for operational control, over matters which he had little practical knowledge, is demonstrated in the following message:

The escape of Emden from the Bay of Bengal is most unsatisfactory, and I do not understand on what principle the operations of four cruisers Hampshire, Yarmouth, Dupleix and Chikuma have been concerted. From the chart, they appear to be working entirely disconnected and with total lack of direction. Who is the senior captain of these four ships? Is he a good man? If so, he should be told to hoist a commodore’s broad pennant and take command of the squadron which will be detached temporarily from the China Station and all other duties, and should devote itself exclusively to hunting Emden. She appears to be making for a coaling place in the Maldives; but anyhow orders should be drafted which will ensure these four ships hunting her in combination and continuously ….

These Whitehall musical chairs led to great instability, with Churchill in October 1914 being forced to seek the now 70-year-old Sir John Fisher to once again take the reins. Churchill persuaded Fisher to support his passionate advocacy of the Dardanelles campaign and when this unfolded into disaster Fisher resigned after only six months in office, saying he refused to work any longer with Churchill. Churchill, who had become supreme ruler at the Admiralty, was now seen as disaster prone.

It seems the Army were also not averse to courting the First Lord’s attention to champion a cause. General Sir Ian Hamilton’s diary entries concerning preparations for landings at Gallipoli mention the need for large self-propelled transport lighters with bullet-proof bulwarks, the prototypes then thought to be under construction.

If I can possibly get a petition for these through to Winston we would very likely be lent some and with their aid the landings under fire will be child’s play to what it will be otherwise. But the cable must get to Winston: if it falls into the hands of Fisher it fails, as the sailors tell me he is obsessed by the other old plan and grudges us every rope’s end and ha’porth of tar that finds its way out here.

While not directly related to naval issues, Charles Bean, author of the Australian Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, provides the following none too subtle and perhaps biased summary of the Gallipoli campaign: So through Churchill’s excess of imagination, a layman’s ignorance of artillery, and the fatal power of a young enthusiasm to convince older and slower brains, the tragedy of Gallipoli was born.Churchill later responds to the criticism in the following terms: It is my hope that the Australian people, towards whom I have always felt a solemn responsibility, will not rest content with so crude, so inaccurate, so incomplete and so prejudiced a judgement, but will study the facts.

Next was the tragedy and resultant great loss of life on 22 September of the three cruisers Aboukir, Cressy and Hogueto the single submarine U-9. Newspapers quickly pointed the finger of blame at Churchill and Battenberg. In The World Crisis which he wrote after the war Churchill defends himself, pointing out that on 18 September he had asked for the cruisers to be withdrawn because they were exposed, but Battenberg had let them stay until more appropriate ships could be found.

Winston’s impetuous nature and adventurous spirit can be seen in his rush to Antwerp when it was besieged by German forces. On 5 October he telegraphed the Prime Minister asking that he might be permitted to resign as First Lord and take charge of the British forces in Antwerp, of which the poorly trained Royal Naval Division formed a major part. The First Lord was sensibly told to return to his post and the Belgium city capitulated a few days later.

Churchill was instrumental with Fisher in promoting the talented John Jellicoe, above others, as Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet. However when Fisher resigned Jellicoe wrote to him: We owe you a debt of gratitude for having saved the Navy from a continuance in office of Churchill, and I hope that never again will any politician be allowed to usurp the functions that he took upon himself to exercise. Perhaps stung by this barb, Churchill writing many years afterwards in The World Crisis describes Jellicoe’s cautious approach at the Battle of Jutland as: the only man on either side who could lose a war in an afternoon.

Army service at the front

These events were to become a permanent blight on Churchill’s career and he was forced out of the Admiralty. As a face saving measure in early 1915 he was made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a sinecure without executive power. On 15 November 1915 Churchill resigned his ‘ministry’ but remained a member of parliament and sought to regain prestige by rejoining the regular Army, using his position as a Major in the territorial regiment, the Oxfordshire Hussars. Just shy of his 41st birthday this middle aged man, used to good living, with limited military experience, went to France for familiarisation training with the Grenadier Guards.

Many years before, on leaving Sandhurst Churchill, who was below average height, was adjudged too short for the infantry, resulting in his commission with a mounted regiment (the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars). He must have looked somewhat out of place in a Guards regiment of six-footers. Using all his family contacts and political influence, in January 1916 Winston, now a Lieutenant Colonel, was appointed in command of the 6th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers, where to his credit he saw duty at the front.

After a few tours of duty Churchill and the Army agreed to part company and in March 1916 he resigned his commission to re-enter politics. It took some while to find him a position of responsibility, but in July 1917 he was appointed Minister of Munitions but kept well clear of Cabinet and this time began to demonstrate a greater level of political maturity.

Churchill’s War with the Bolsheviks

With the end of hostilities Churchill was made Secretary of State for War which also combined the new Air Ministry. Now largely forgotten, towards the end of WWI allied forces, prominently British, were supporting White Russian (Tsarist) forces involved in civil war against the Red (Bolshevik) Army. Churchill, who was enthusiastic, persuaded the government to commit 40,000 British troops and numerous warships to this cause, in his words: ‘to strangle at birth the Bolshevik State’.

An allied force also included 5,000 Canadians, but Prime Minister Billy Hughes refused Australian involvement. However, in 1918 a number of Australian troops serving in Europe resigned, re-enlisted in the British Army, and saw service in Russia (a possible comparison with contemporary issues of young Australians volunteering to serve in Middle East). What became known as “Churchill’s War” or the “Whitehall Foley” became increasing unpopular, resulting by 1920 in a withdrawal of allied support to White Russian forces.

Turbulent times

On 13 February 1921 Churchill was appointed Colonial Secretary, again with Australian responsibilities, and the following month he was part of the British delegation to a Middle Eastern Conference in Cairo. This led to a political settlement in Iraq and Transjordan and to a policy allowing the establishment of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine.

If only the consequences of these policies could have foreseen the world might have been spared its present unhappy state. In December of this year agreement was reached for the partition of Ireland with the southern portion being granted Dominion status, coming under the responsibility of the Colonial Secretary. However his days were numbered, as in a 1922 general election when Labour came to power, Winston lost his seat.

The Labour Government was short lived being brought down by perceived links with the Soviet Communist Party. At fresh elections in 1924 Churchill was returned to parliament where he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Following a period of industrial unrest with a national strike, Labour was again returned to office in 1929 and Churchill was obliged to support his meagre MP’s pay with writing and American lecture tours.

While on the sidelines in September 1931 the British Atlantic Fleet mutinied in what became known as the Invergordon Mutiny. As an economy measure a 10% pay cut was introduced across the public sector, but to many junior ratings the reduction was 25%. These sailors refused work and the fleet was forced to a standstill until the worst of these measures was undone.

In December 1934 in the midst of the Great Depression, Clementine Churchill left the family on a five month voyage to the Far East, Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Islands as a guest of Lord Moyne (Walter Guinness) aboard his motor yacht Rosaura is search of Komodo dragons for the London Zoo. In Singapore Clementine took the opportunity of touring the dockyard. She gave Winston a remarkably detailed account of its construction, and the reduction of its scope and facilities due to the Government’s paring of defence expenditure. In Sydney she met again with family friend Margery Street. Margery was Churchill’s long-term secretary who joined the household in 1921 but had returned to her homeland of Australia in 1933.

Returned to power

With Britain once more at war with Germany in September 1939, Churchill was again offered his old post of First Lord of the Admiralty, with a seat on the War Cabinet and Admiralty House again his home. In May 1940 with a war going badly and a lack of confidence in his Government, Neville Chamberlain resigned. The King sent for Churchill and asked him to form a government.

An early and contentious decision was to seek the surrender of French warships based in North Africa. The French Admiral Darcan proved an irritant to Churchill because of his lack of enthusiasm to back Britain. To prevent the French ships falling into enemy hands the seemingly unthinkable happened, with British and French warships opening fire on each other, resulting in the destruction of major French warships with the loss of 1,300 lives.

Fighting on the beaches

Churchill is best known for his classical use of rhetoric where he reminds the audience of the main points of the speech to influence their emotions. One of his finest oratical moments is his speech delivered to the House of Commons on 4 June 1940 widely known as ‘We Shall Fight on the Beaches’, of which but a small extract is quoted. Radio was one of Churchill’s greatest assets, as his invigorating speeches were broadcast to millions who greatly appreciated his warm-hearted vigour and contempt for the enemy.

We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island, or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until in God’s goodtime, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and liberation of the old.

In comparison to these stirring sentiments there is another human side which alludes to the pressure being exerted on the great man. During these demanding times Clementine and her husband saw little of each other and they had grown used to exchanging notes. Amongst those surviving is one dated 27 June 1940, which in part reads:

My darling

I hope you will forgive me if I tell you something I feel you ought to know. One of the men in your entourage (a devoted friend) has been to me and told me that there is a danger of your being generally disliked by your colleagues and subordinates because of your rough sarcastic and overbearing manner. It seems your Private Secretaries have agreed to behave like schoolboys and take what’s coming to them and then escape out of your presence shrugging their shoulders. Higher up, if an idea is suggested (say at a conference) you are supposed to be so contemptuous that presently no ideas, good or bad, will be forthcoming. …… My darling Winston I must confess that I have noticed a deterioration in your manner; and you are not as kind as you used to be. ….. I cannot bear those who serve the Country and yourself should not love you as well as admire and respect you. Besides you won’t get the best results by irascibility and rudeness. They will breed either dislike or a slave mentality (rebellion in war time being out of the question!).

Please forgive your loving devoted and watchful, Clemmie.

We surely have Clementine to thank for broaching a subject that few dared and hopefully bringing Winston back to reality. That such a document has survived is testament to the completeness and honesty of the Churchill family archive.

Another person who rates little more than an historical footnote who held considerable sway over Churchill was a junior but ‘old and bold’ naval officer, Lieutenant Commander Charles Ralphe (Tommy) Thompson, RN. Thompson, who had served as a submarine commander during WWI became known to Churchill when he served in HMS Enchantress. When Churchill returned to the Admiralty in 1939 Thompson was appointed his flag lieutenant and followed his leader to Downing Street when he became Prime Minister. Thompson, a confirmed bachelor, was never far from his master’s side and accompanied him on overseas missions until he retired as a Commander at the end of the war when aged 50.

Stephen Roskill in his prodigious History of the War at Sea commenting upon Churchill’s meddling in the appointment of senior officers, suggests Dudley Pound’s unhappy appointment as First Sea Lord was based on Churchill’s tendency to surround himself with the pliable or like-minded. Here the dedicated Pound was held responsible for some of his master’s more outrageous demands, proposals and comments. Roskill also records that Churchill was wary of advancing Cunningham to First Sea Lord as he was tough, assertive and not susceptible to Churchill’s powers of persuasion.

The darkest days

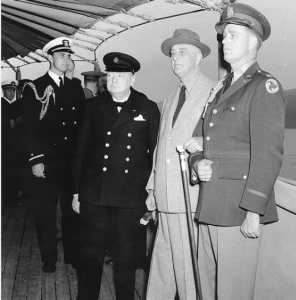

There were two voyages to America in 1941 to meet President Roosevelt, the first in August in HMS Prince of Wales and the second in December in HMS Duke of York. On 26 December Churchill suffered a slight heart attack necessitating recovery in Florida. He returned home again in a Boeing flying-boat after an absence of five weeks. In February 1942 came some of the darkest days with the surrender of Singapore, the largest capitulation in British history. This defeat also marked a position from which British prestige in the Far East would never recover and the loss of a mighty empire. Australian faith in British support was undermined and for the foreseeable future our destiny was then linked to that of the United States.

Perhaps the greatest and most sincere complements are those paid by foes. In this respect Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, the Commander-in-Chief of the German Navy and, after Hitler’s death the Head of State, writing in his memoirs says: Churchill, who has an excellent grasp of the requirements of naval warfare such as is very seldom to be found in a statesman and politician, appreciated this point (cross training of submariners in surface warfare) during the Second World War. In 1942, he entrusted to Admiral Sir Max Horton, a most experienced submarine commander of the First World War and later captain of a battleship and admiral in command of cruisers, the task of organising and protecting the Atlantic convoys, which were of such vital importance to Britain – and by so doing made him my own personal adversary-in-chief.

The Big Three

With American aid in 1943 the fortunes of the Allies began to improve, with the Germans being pushed back in North Africa and by Russia on the Eastern front. This was also the year of great conferences with the meeting of the ‘Big Three’, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin in Tehran. It was here that Churchill first began to recognise the Sun was fast setting on his empire and that future world events were being largely decided by American and Russian interests. This may help explain Churchill’s continued support to obsessive bombing of German cities, at the expense of greater number of air assets being afforded to the fight against submarines. By bombing Germany he could demonstrate to Stalin that Britain was creating pressure against Axis forces on the Eastern front. In February 1945 the same leaders met at the Yalta Conference where Britain again found her bargaining power weak, with a green light given to Russian domination over Eastern Europe.

Following victory in Europe the Labour Party refused to continue to support the war-time coalition government, forcing new elections. Polling Day was fixed for 5 July 1945 where the old warrior, now 70 years old, who had led his nation to victory, was pitted against a younger and more dynamic adversary. Labour was able to exploit thinking that the Conservatives, and especially Churchill, was irresponsible and out of touch with ordinary people. The outcome was a landslide win for Labour. The great statesman painfully watched the unfolding of the empire he so dearly loved and the demise of the great navy that had protected it.

Out of office and back again

While out of office Churchill perhaps unwisely retained leadership of his party. His days were now filled with what he enjoyed most, writing and painting, with more time, especially during the winter months, spent taking agreeable holidays abroad in warmer climes. In late 1951 the Labour Government called an election which it lost and Winston, now 76 years of age and in failing health, was called upon once more to form a new government. It was unfortunately a time when the health of his wife and greatest supporting prop was also failing. In 1954 one of his greatest personal triumphs and accolades was the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

There was forever reluctance by the old war horse to relinquish power but without the strength and stamina to fight he eventually resigned at Easter 1955. An election was called, with Winston still retaining a seat in parliament but under Prime Minister Anthony Eden. The Churchills spent much of their remaining years together in the South of France, frequently accepting hospitality from the very rich including the Canadian newspaper magnate Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) and the Greek shipowner Aristotle Onassis.

An end to a remarkable voyage

On a Sunday morning on 24 January 1965 Sir Winston Spencer Churchill died aged 90 at his London house. He was accorded the rare honour of Lying-in-State (the first commoner since the Duke of Wellington) and given a state funeral. The pall bearers were from the Grenadier Guards with which he had fought during WWI, and his coffin was placed on a gun carriage drawn by 120 naval ratings, passing slowly through the streets of the capital to St Paul’s Cathedral. Following the service the bier was then taken to Tower Pier for a final voyage upstream to Waterloo Station; here bands played ‘Rule Britannia’ accompanied by a 17-gun salute. Even the giant-giraffe like dockside cranes dipped their jibs to the cortege. The body was taken by train for its final resting place at Blandon near Blenheim Palace, where he had been born. After the funeral President Eisenhower and our Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies made impressive broadcasts to the American people and the peoples of the Commonwealth respectively. With his passing the Churchill country home at Chartwell in Kent, with many of its historic contents, was bequeathed to the National Trust.

Dr Charles McMoran Wilson (Lord Moran) was Winston’s physician from 1940 until his patient’s death in 1965. The following year he published Winston Churchill – The Struggle for Survival based on his diaries concerning his illustrious patient. The book was later serialised in The Times. Many, including the Churchill family, were highly critical of this breach of medical ethics. However Moran does provide a unique insight into a private life which we should not otherwise know. There is mention of Churchill’s depressive tendency, the ‘Black Dog’, and his upsetting mood swings. Moran admits he gave his patient drugs to help bolster his spirits. However Moran downplays the effects these episodes had on Churchill’s overall performance.

The first ship named after him was an ex United States Coast Guard cutter commissioned into the Royal Navy in 1940 as HMS Churchill. She was later transferred to the Soviet Navy and was sunk in action in 1945. In 1967 the first of a new class of nuclear submarine was laid down as HMS Churchill. HMS Conqueror, another of this class, is best known for sinking the Argentinean cruiser ARA General Belgrano in the 1982 Falklands War. HMCS Churchill was a Royal Canadian Navy shore establishment from 1950 to 1966.

Lady Churchill was to spend another 12 years widowed, comforted by her family. She died in her 92nd year in December 1977. Her funeral service was held at Westminster Abby, and was attended by members of Winston’s old regiment the Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars (4th Hussars) and officers and men from HMS Churchill.

Summary

In 1940 a short flabby man of 65, a difficult man, a solid smoker and drinker, who most considered past his prime, took on the world’s toughest job of beating a triumphant Hitler. His pugnacious features became known to millions and epitomised the fighting spirit of the British Bulldog. But for Churchill, with his acknowledged shortcomings, there may have been no Anzacs winning their spurs at the Dardanelles, a great graving dock may never have been built and Garden Island would still be totally surrounded by water. In the darkest days when Britain stood alone it would have been far easier to seek compromise with the enemy; if this had occurred the world would be a far different place from what we know today and Australian independence not guaranteed.

His magnificent mastery of prose produced so powerful a potion it became a tonic which fortified the national spirit, for with him there was no need for lesser mortals to spin tales. With Churchill at the helm his ship never wavered from what he considered the true course and his indomitable fighting spirit was a major factor in bringing about victory in hopefully our last world war.

We are grateful to Jim Craigie who provided research material for this article.