- Author

- Turner, Mike

- Subjects

- Naval history, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Mike Turner

A bombing/mining blockade campaign against mainland Japan in 1945 was very successful. By June Japan recognised that she was defeated, and all she could do was negotiate surrender terms. The Allied Potsdam Declaration of 26 July called for unconditional surrender by Japan, but this was rejected. Strategic atomic bombs dropped on Japan on 6 and 9 August 1945 had an enormous psychological impact, and Japan was caught unprepared for the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on 9 August. Emperor Hirohito announced unconditional surrender on 15 August 1945, and the formal surrender was on 2 September.

American bombing of the Japanese mainland

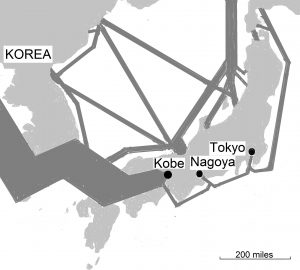

After the Marianas were recaptured the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) XXI Bomber Command was based at Guam, Saipan and Tinian, Figure 1 refers. At full strength the command had a thousand B-29 Superfortress bombers in five wings. Bombing the Japanese mainland commenced on 24 November 1944.

Initially bombing was high-level daytime area-bombing against major targets, particularly aircraft factories. Incendiary bombing of major cities was at night from only 5,000 feet, commencing on 9 March. Cities were devastated by incendiary bombing, for example fire eventually destroyed half of Tokyo. There was an intensive propaganda campaign alongside firebombing raids with 50 million leaflets dropped from May to July. From June to the end of the war there were ‘precision’ attacks on important industrial targets on days when the weather over Japan was clear, and radar navigation was used for incendiary attacks on small cities on overcast days. In addition, from late June the 315th Wing conducted low-altitude night-time pathfinder missions, and virtually shut down the oil refineries.

From 7 April P-51 Mustang fighter-bombers based at Iwo Jima escorted B-29s as well as attacking ground targets. P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers based at Okinawa made frequent day and night patrols over Kyushu to disrupt Japanese air units, commencing on 17 May.

USN Task Force 58 included 16 aircraft carriers, and its first bombing of Japan was on 16 and 17 February 1945. This was tactical bombing of airfields to assist in the invasion of Iwo Jima on 19 February. The second bombing operation was against airfields on 18 March and warships at Kure on 19 March to assist in the invasion of Okinawa on 1 April 1945. The battleship Yamato, the aircraft carriers Amagiand Ryuhoand 14 other ships were damaged. Irregular bombing operations continued in April and May. On 27 May TF 58 became TF 38 when Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey resumed command from Admiral Raymond Spruance. Bombing continued and became a sustained intensive operation solely against mainland Japan in July. The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) joined in these air strikes as TF 57. RAN Q and N class destroyers and Bathurst class corvettes were in TF 37, and one of them participated in the bombardment of Japan. On the night of 17/18 July HMAS Quiberonwas in the screen for HMS King George Vand six US battleships bombarding the Hitachi area of Honshu. On 24, 25 and 28 July USN aircraft attacks on Yokosuka Naval Base and targets in the Inland Sea sank the carrier Amagi, the ‘battleship-carriers’ Ise and Hyuga, the battleship Horuna, and five cruisers, thereby virtually eliminating the Japanese Fleet. In July air strikes also sank or disabled ten of the twelve train ferries that carried the vital coal supplies from Hokkaido to Honshu. The last attack by TF 38 on Japan was aborted on 15 August when Japan surrendered.

Bombing seriously impaired the Japanese war machine, but on its own would not have forced Japan to surrender.

Japanese influence minesweeping capability

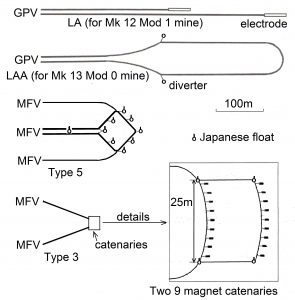

The Japanese used small wooden-hull vessels, such as motor fishing vessels (MFV), for sweeping influence mines. The standard magnetic sweep was the Type 3 magnetic sweep based on British magnetic sweep gear captured at Singapore, Figure 2 refers. (The RN single catenary magnet sweep was a ‘Bosun’s Nightmare’and was only used as an emergency sweep in the first few months of the war). The 8kg magnets had to be within 3m of a mine for actuation. Not only was the swept width a miniscule 25m, but magnet depth had to be adjusted as the depth of water varied or the magnets had to be dragged along the sea bed.

The Japanese also used a Type 5 closed loop electric cable sweep based on the German KFRG sweep, and the height of the loop above the sea bed could not exceed 10m.The Japanese Navy did not have diverters (a combination of a float and otter board) to spread the loop so used two ships instead. Unlike the Allies, Japan did not have buoyant electric cable, and the cable was supported by floats. Both types of Japanese sweep were fairly technically effective in sweeping American magnetic mines, but the Admiralty, quite rightly, described them as ‘slow, clumsy and dangerous’. The RAN used small wooden-hull General Purpose Vessel (GPV) minesweepers for sweeping two types of American magnetic mine at northern Bougainville in 1948, and its two types of sweep are compared with the Japanese sweeps in Figure 2.

The only Japanese acoustic sweep was the Hatsuondan sound bomb. There was a 50 percent probability of sweeping the early audio frequency A-3 acoustic sensors, however bombs were ineffective against low frequency A-5 acoustic sensors that became available in May 1945.

Unsweepable magnetic-pressure mines also became available in May 1945. Japanese countermeasures were to slow traffic down to a ‘safe speed’ and to drag mines out of a channel using a bottom trawl.

By the end of the war Japan had 20,000 men and 349 ships for minesweeping. The Japanese had complete intelligence on American mines since about 10 percent of aerial mines fell on land. However inferior Japanese technology made Japan vulnerable to a very heavy attrition mining campaign.

The mining blockade of Japan – Operation STARVATION

In July 1944 Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, C-in-C US Pacific Fleet, put a plan for mining Japanese home waters to the US Army, and it met strong opposition. On 7 November Nimitz wrote to Major General ‘Hap’ Arnold, Commander General of the USAAF, proposing B-29 mining of Japanese home waters, beginning on 1 January 1945. Arnold believed that a bombing/blockade campaign could force Japan to surrender without an invasion. On 22 December 1944 Arnold directed Brigadier General Hansell, commanding USAAF XXI Bomber Command, to prepare his force for a mining effort. Arnold was not satisfied with Hansell, and on 20 January 1945 replaced him with General Curtis LeMay. He supported mining, and within six days of taking over command he wrote to Washington with a plan to use 313th Bombardment Wing at Tinian to deliver 1500 mines per month. Training combat crews for aerial mining began in February 1945. The eventual complete blockade of Japan was largely due to the exemplary cooperation of LeMay and Nimitz.

The strategic aims for the mining operation were to:

- Prevent the import of raw materials and food into Japan.

- Prevent the supply and deployment of Japanese military forces.

- Disrupt internal marine transportation within the Inland Sea.

Mining commenced on 27 March, and the immediate tactical aim was to prevent Japanese naval units deploying to assist in the defence of Okinawa.

Japan depended on sea traffic for vital imports such as oil and food. The vast majority of domestic transportation, 75%, used coastal and inland waterways. A successful blockade would virtually stop industry, and a considerable part of the population would starve – hence ‘Operation STARVATION’.

A USN Mine Modification Unit at Tinian optimised mine sensitivity and logic settings based on F-13A Superfortressaerial reconnaissance of shipping. B-29 bombers used radar for navigation, and laid ground mines at night by parachute from 5,000 to 8,000 feet, the average mine load being four 450kg mines and four 900kg mines. In all 12,135 USN ground mines were laid – about 5,000 magnetic, 4,000 acoustic and 3,000 magnetic-pressure. Japanese fighter defence was ineffective, and only 16 aircraft were lost from all causes. There were also 186 mines laid in Korean waters in June by PB4Y-2 Privateer patrol bombers of Fleet Air Wing One based at Okinawa.

Shimonoseki Strait was the primary target, and was as narrow as 360m. Most of Japan’s imports passed through this strait, and about half of all Japanese shipping used the strait for Hiroshima, Kobe, Osaka and other ports in the Inland Sea. Blocking this strait would also deny access to 18 of the 21 major shipyards for repairs. It would also force naval units ‘holed up’ in the Inland Sea to exit on the east coast which, unlike the west coast exits, was under observation by USN submarines. Operation STARVATION, in five phases with Shimonoseki Strait in every phase and differing other targets in each phase, continued until the Japanese surrender.

The land battle on Okinawa began on 1 April, and mining delayed the 73,000-ton battleship Yamato, a cruiser, and eight destroyers leaving the Inland Sea via Bungo Straits for Operation TEN-GO until 6 April. The exit was observed, and the next day carrier aircraft sank Yamato, the world’s largest battleship, the cruiser and four destroyers.

There was a critical shortage of fuel for the Navy, for example when Yamato departed for Okinawa the fuel situation made it a one way ‘suicide’ mission. The effect of mining on shipping traffic is readily apparent from a comparison of Figures 3 and 4, where the width of a ‘shipping lane’ is proportional to traffic density. Figure 3 shows all eastern ports closed, no traffic in the Inland Sea and only a trickle to the western ports. The tonnage of operable shipping remaining had been reduced to only one sixth of the tonnage in 1941, and was barely half that required for national subsistence. An official Japanese Survey of National Resources in June 1945 reported that the difficulties of transportation were insurmountable. Takashi Komatsu, director of a Tokyo steel company, stressed that although bombing badly hurt factories, the denial of essential raw materials to them was a greater loss.

The population was starving, civilian rations being 16% below the subsistence level. Malnutrition negatively affected the immune system, and there was a general increase in cases of diseases such as dysentery, beriberi, gastrointestinal disease, typhoid fever and particularly tuberculosis.Every possible ship was used in 1945 to import food, however the import of food (and almost every other commodity) had virtually ceased due to the complete blockade. For example no sugar, a commodity for which Japan had depended on outside supplies for 80% of her consumption, had been received since March when a mere 160 tons came in. The shortage of rice was exacerbated by the rice crop being disastrous, the worst since 1910. It was expected that up to 10 million would die of starvation by the end of winter in February 1946 (this was averted by generous US post-war food supplies). Captain Kyuzu Tamura, head of the Japanese Minesweeping Section, stated ‘The result of B-29 mining was so effective against the shipping that it eventually starved the country. I think you [the US] could probably have shortened the war by beginning earlier.’ But for strong Army opposition mining would have commenced at least three months earlier, however it is not possible to estimate when starvation would have induced the Emperor to order surrender.

Kamikaze ‘suicide’ bombers

Bomb-laden kamikaze aircraft were generally converted aircraft, such as A6M ‘Zero’ fighters or Aichi D3A ‘Val’ dive bombers. Inthe Leyte Gulf on 21 October 1944 (Trafalgar Day) HMAS Australia became the first ship hit by a kamikaze, a Val. The Commanding Officer, Captain EFV Dechaineux and 13 other officers and ratings were killed. Various total losses for the war have been reported, but about 2 800 kamikaze aircraft sank 34 USN vessels and damaged 288 others. Losses included three escort carriers and thirteen destroyers.

The preferred defence against kamikaze aircraft was to attack them on the ground, but this was difficult since they were camouflaged and well dispersed. When RN carrier aircraft were tasked with attacking kamikaze aircraft on the ground in Kyushu they found them difficult to locate.

The invasion of Okinawa – Operation ICEBERG

The battle at Okinawa in April-June 1945 was an essential step towards an invasion of Japan. The existing bases in the Mariana Islands were only suitable for strategic B-29s, and Okinawa would provide a base for tactical aircraft supporting an invasion of Japan, Figure 1 refers. For Operation ICEBERG the USN 5th Fleet deployed four task forces including TF 57, the British Pacific Fleet under Vice Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings RN, and there were a number of HMA Ships in TF 57.

During this battle there were 250 kamikaze sorties from Formosa and 1,650 kamikaze sorties from Kyushu, including 400 on 6 April. They sank 24 USN vessels, including eight destroyers, and damaged another 198. RN aircraft carriers had armoured decks, whereas USN aircraft carriers had wooden decks to maximise the number of aircraft carried. All five RN aircraft carriers in TF 57 were hit by kamikazes, but were not put out of action. During this battle five CV and two CVE American carriers were hit by kamikazes and sent to navy bases for repairs, particularly repairs to wooden decks. The USN had 4,907 fatalities, and this exceeded the 4,675 Army fatalities caused by extremely heavy ground fighting.

This battle provided an indication of the fierce resistance to be expected on the Japanese homeland. Japanese defence of Okinawa was fanatical, there being 77,166 Japanese fatalities and only about 16,000 survivors. Land battles caused 39,000 American casualties, and there were 7,700 Navy casualties, mainly due to kamikaze attacks. (Casualties in this article are KIA, MIA and wounded).

Planning the invasion of Japan – Operation DOWNFALL

At their meeting in Quebec in September 1944 Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt agreed on a broad policy of defeating Japan by a blockade and bombing of mainland Japan followed by invasion.

Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall and his Army planners believed that Japan’s unconditional surrender could only be assured by invasion of its home territory. Fleet Admiral Ernest King, Chief of Naval Operations, General ‘Hap’ Arnoldand anumber of key Navy and Army Air Forces officers argued that a combination of a mining blockade and aerial bombing could produce a Japanese surrender without the need for a ground invasion. Debate on the necessity of invasion was to continue to the end of the war.

Operation DOWNFALL was:

- The occupation of small offshore islands to provide safe anchorages for support vessels and ships damaged during the preliminary invasion of Kyushu, Figure 3 refers.

- The preliminary invasion of southern Kyushu (Operation OLYMPIC) at three sites by fourteen divisions on 1 November 1945. (The original date of 1 December was brought forward to 1 November at the request of Macarthur and Nimitz who were concerned about the weather in December).

- The main invasion of Honshu (Operation CORONET) by 25 divisions (many more than Normandy) on 1 March 1946using southern Kyushu for air support. Two invasion forces would combine for an attack on the Tokyo plain.

After the German surrender on 8 May 1945, arrangements were made for Truman, Churchill, and Stalin to meet in Potsdam on 15 July to try to settle the post-war arrangements for Europe and to reach agreement on coordinated Allied military operations against Japan. In preparation for this meeting Truman set up a meeting with his top level military staff on 18 June. Truman was ‘very much disturbed’at the American casualties at Okinawa, and requested an estimate of losses for Operation OLYMPIC.

The Joint War Planning Committee (JWPC) and General Douglas Macarthur estimated OLYMPUS casualties to be about one hundred thousand. The JWPC, Macarthur and Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz estimated the total casualties for invasion to be about a quarter of a million. (As a yardstick the casualties for Normandy, from D-Day through 48 days of conflict, were 63,360).The Joint Chiefs were very much in favour of Operation OLYMPIC, and were concerned that their high casualty estimates could turn Truman against it.

At the 18 June meeting with the President, Marshall presented a report which omitted estimated casualty figures for Kyushu, but included ‘smokescreen’ figures for Leyte, Luzon, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. The report also included the judgment that ‘There is reason to believe that the first 30 days in Kyushu should not exceed the price we have paid for Luzon [31,000]’ and Truman authorized the invasion of Kyushu. On 18 June only three combat divisions had been fully confirmed on Kyushu, with a fourth believed to be on the way. Marshall stated that by November the Japanese would have eight divisions (referring to six combat and two depot divisions) and a total of 350,000 military personnel on Kyushu.

The US Navy could expect heavy losses from kamikazes for Operation OLYMPUS, a much larger operation than Operation ICEBERG. One series of messages indicated that up to 2,000 obsolete planes and trainers were being assigned to equip and train units for kamikazemissions, including night attacks by biplanes and other older model aircraft. There would not be early warning from radar picket destroyers since low flying kamikazes would only be detected as they left the coast.

New intelligence from intercepted messages led to dramatic increases in estimates of Japanese defence, and on 4 August the Military Intelligence Service confirmed that there were now 14 divisions with 600,000 personnel on Kyushu. (Post-war data verified the number of divisions, however there were 900,000 troops). This increase in Japanese troop strength to parity with the American Army mandated a fundamental re-examination of US invasion plans. Macarthur and Nimitz were requested to review their estimate of the situation and prepare plans for operations against alternate objectives; however any development of alternative plans was overtaken by fast moving events.

Atomic bombs

Truman formally approved the dropping of the atomic bomb on 2 August, two days before intelligence dramatically increased the strength of the Japanese defences on Kyushu. Paucity of in siturecords, due to the secrecy surrounding the atomic bomb, means that there is no conclusive indication of Truman’s reasoning for authorising its use. Truman was very concerned about the casualties to be expected from invasion. Russia had reneged on assurances for the occupation of Europe. Truman was mindful of political consequences if the imminent Russian invasion of Manchuria occurred before the bomb was dropped and the Soviet Union had time to penetrate deeper than agreed, possibly as far as Hokkaido.

The Joint Chiefs expected that nine atomic bombs would be available before the invasion of Kyushu on 1 November.Considerationwas being given to droppingstrategic bombs prior to the invasion followed by tactical bombs during the invasion.The use of tactical bombs was based on the erroneous assumption that after 48 hours radiation would no longer prevent troop movement.

A13 kiloton uranium atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August. From their own atomic bomb research the Japanese appreciated the enormous effort required to build a single atomic bomb, and were convinced that America could not have many bombs. A 21 kiloton plutonium bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August to, inter alia, try to convince the Japanese that there were many more bombs.

The two bombs resulted in about one hundred thousand immediate fatalities, but this did not lead to unconditional surrender on 15 August. There were also one hundred thousand fatalities from the initial incendiary raid on Tokyo on the night of 9/10 March 1945. The impetus for Japanese unconditional surrender due to the bomb was the psychological impact of spectacular instant total destruction of large areas by a completely new type of weapon.

Soviet-Japanese War of 1945

The 1875 Treaty of St. Petersburg resulted in Japan ceding Sakhalin Island to Russia and Russia ceding the southern half of the Kuril Islands to Japan. The Russian Army and Navy were defeated by Japan in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, and the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth resulted in Russia ceding the southern half of SakhalinIsland to Japan. Also Russia recognized Korea as part of the Japanese sphere of influence, and agreed to evacuate Manchuria. Japan annexed Korea in 1910.

President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Generalissimo Stalinattended the Yalta Conference in February 1945. Roosevelt considered that a Soviet declaration of war with Japan would assist America in invading Japan. Stalin agreed to Allied pleas to declare war on Japan within three months of Germany’s surrender. In return Russia would be given a sphere of influence including Manchuria, Sakhalin Island and the Kuril Islands. America assisted the Russian Navy for the invasion of Sakhalin Island and the Kuril Islands. Project Hula was the largest transfer of the war and took place in the Territory of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands from March to September 1945. At Cold Bay the US Navy transferred 149 ships, including 30 Large Infantry Landing Craft, and trained 12,000 Soviet Navy personnel.

The Soviet Union invaded Manchuria on 9 August, exactly three months after Germany’s surrender, against a surprised and unprepared Japan that had only prepared for an invasion of Kyushu. The invasion was from the west, north and east and the defeat of Japan’s Kwantung Army was swift and devastating. On August 18 there were five Soviet amphibious landings: three in northern Korea, one in Sakhalin, and one in the Kuril Islands. The Soviet offensive was terminated on 2 September, the day of the formal surrender.

There was an understanding that Soviet Union would occupy Korea north of the 38th parallel and America would occupy south of the 38th parallel. An American occupation force landed at Inchon on 8 September.

Japanese unconditional surrender

Japan was controlled by theSupreme Council for the Direction of the War (the Big Six) nominally appointed by the Emperor:Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of War, Minister of the Navy, Chief of the Army General Staff and Chief of the Navy General Staff.Army policy remained as it was in Okinawa ‘fight to extinction rather than surrender’, and this policy was adopted by the Big Six on 6 June. The people were starving and transport and industry were in chaos. The Emperor was concerned at the effect that blockade/bombing was having on his people. On 22 June he summoned the Big Six to a meeting and stated that ‘I desire that concrete plans to end the war, unhampered by existing policy, be speedily studied and that efforts made to implement them’.Private entreaties were made in late June to the (technically) neutral Soviet Union to mediate peace on terms more favourable to the Japanese than unconditional surrender. The Soviet Union stalled peace negotiations, since it did not want Japan to surrender before it completed moving troops from the Western Front to the East to invade Manchuria.The Allied Potsdam Declaration of 26 July called for unconditional surrender by Japan to all the Allies to avoid‘prompt and utter destruction’.

On 9 August the second atomic bomb was dropped and the Soviet Union had invaded Manchuria. Japanese leaders were divided into two camps regarding surrender. One camp favoured unconditional surrender except for the Emperor being retained. The other camp insisted on three more (totally unacceptable) conditions:no occupation of Japan, disarmament left in Japanese hands, and war criminals tried by Japanese tribunals.Emperor Hirihito stated ‘I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer’and ordered the Big Six to adopt the single-exception unconditional surrender terms, and they informed the Allies on 10 August.

Exchanges between the Allies and Japan did not produce an immediate surrender, and President Truman ordered a resumption of attacks against Japan at maximum intensity ‘so as to impress Japanese officials that we mean business and are serious in getting them to accept our peace proposals without delay.’The United States Third Fleetshelled the Japanese coast. In the largest (and longest range) bombing raid of the Pacific War, more than 400 B-29s attacked northern Hokkaido during daylight on August 14, and more than 300 that night. The Emperor convinced his military leaders to accept the Allied terms. His surrender speech (recorded late on 14 August) was played on Japanese radio at noon Japanese time on 15 August.

Surrender was due to three factors – the collapse of Japan due to the blockade/bombing campaign, the atomic bomb and the Russian invasion. Debate continues on the relative importance of the three factors.

Bibliography

Air raids on Japan, < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_raids_on_Japan>Allied Offensive Mining Campaigns, Interrogation Report, (USSBS No. 34) NAV No. 5, HQ US Strategic Bombing Survey, Pacific, 1945Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

<https://en.wikipedia.org/…/Atomic_bombings_of_Hiroshima_and_Nagas>

Battle of Okinawa, < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Okinawa>

BR 1736 (50) (5), The Blockade of Japan,Admiralty, 157Chilstrom, JS, Mines away! The significance of US Army Air Forces minelaying in World War II, thesis, Air University, Alabama, 1992

Cowie, JS, Mines, minelayers and minelaying, Oxford University Press, London, 1949

DiGiulian, T, Kamikaze Damage to US and British Carriers, <www.navweaps.com/index_tech/tech-042.htm>

Duncan, RC, America’s use of sea mines, US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1962

Gill, GH, Royal Australian Navy 1942 – 1945, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1985

S-28, US Naval Technical Mission to Japan, January 1946

Kamikaze https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamikaze>

List of United States Navy losses in World War II, <https://en.wikipedia.org/…/List_of_United_States_Navy_losses_in_World_War_II>

MacEachin, DJ, The Final Months of the War With Japan, CSI 98-10001, Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency

Manhattan_Project, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manhattan_Project>

Morison, SE, History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, Volume XIV: Victory in the Pacific, 1945, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1990

Operation Downfall, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Downfall>

Operation Ten-Go, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Ten-Go>

Potsdam Declaration, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potsdam_Declaration

Project Hula <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Hula>

Rielly, R, Kamikazes, Corsairs, and Picket Ships: Okinawa, 1945,<https://books.google.com.au/books?isbn=1935149911>

Roskill, SW, The war at sea 1939 – 1945, Volume III, The Offensive, Part II, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1961.

Russo-Japanese War <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Japanese_War>

Soviet invasion of Manchuria <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_invasion_of_Manchuria>

Surrender of Japan <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surrender_of_Japan>

The Korean War : setting the stage and brief overview<www.nj.gov/military/korea/factsheets/overview.html>

The Yalta Conference, 1945 <https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/yalta-conf>

Treaty of Portsmouth <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Portsmouth>

Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Saint_Petersburg_(1875)>

XXI Bomber Command, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XXI_Bomber_Command

War with Japan. Volume VI Advance to Japan. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1995

Wright, M, In Search of “Silver Rice”: Starvation and Deprivation in World War II-era Japan, Northern Illinois University, 2010.