- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Kuru

- Publication

- June 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John Harris

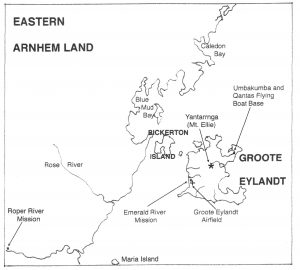

Japan’s sudden entry into WWII, threatening the whole Pacific region, galvanised Naval Intelligence into immediate action to formalise and expand the old pre-war Coastwatcher program in coastal Northern Territory. The Reverend Len Harris1 on Groote Eylandt had been one of the unofficial observers prior to the War. The full story of Len Harris and the old Coastwatcher network was told in Part 1 of this article, in the previous edition of the Review.2This second part of the article takes up the story at Japan’s entry into the War and the subsequent commencement of war in the Pacific.

Len Harris becomes an official Coastwatcher

On 12th December 1941, spurred into action by Japanese attacks, HMAS Kuru under command of LEUT John Bell, RANR was despatched urgently around the north coast and the Gulf of Carpentaria. Bell’s task was to visit the north Australian network of unofficial Coastwatchers, formalise their role, brief them on what and how to report, and provide them with Teleradios. He visited all the mission station staff involved in the old arrangement, including Father John McGrath at the Sacred Heart Mission on Bathurst Island and Rev. Leonard Kentish at the Methodist Mission on Elcho Island. About a week later he reached Groote Eylandt. Kuruanchored near the mouth of the Emerald River. Bell took the ship’s launch up river to the Church Missionary Society (CMS) mission station, the now-abandoned site which is still locally called Old Mission. Len Harris recalled the occasion:

‘Late in 1941, around the middle of December, Captain Bell on the Kuru called at Groote Mission. He told me that the sudden eruption of the War into the Pacific meant that the whole Coastwatching operation had now been formally taken over by the Navy and that it was to be extended and put on an official footing. He asked me if I was willing to be part of this new organisation and serve as an official Coastwatcher. He told me that the Navy had already contacted CMS head office in Sydney and that they had agreed that the decision was up to me. I had not the slightest hesitation. It was after all simply a question of duty. Captain Bell administered the oath and I was sworn in as an official Naval Coastwatcher.

Captain Bell told me that the reorganised group included the old Mission Coastwatchers, all the ones I knew from before like Father John on Bathurst Island and Len Kentish on Elcho Island. They needed us because we were the only ones always in touch with the Aborigines. He told me that they would fill in the gaps between the missions with naval officers. I eventually got to know some of them too, like Petty Officer Jack Jensen on Marchinbar Island. They lived a pretty isolated life with supplies dropped off by the Kuruevery now and then.

After I was officially sworn in, Captain Bell gave me the Playfair Code instructions3and the secret Code Word which I have never revealed – not even now! It also functioned as my code name, I think. He taught me how to use the Code and issued me with cards of silhouettes of both Japanese and allied planes and ships so I could recognise them. He only stayed the one day. He returned to Kuru before dark and left for Mornington Island the next day. But the great thing he did before he left was to give me a brand new Teleradio 3C. This was indeed a terrific improvement over my old pedal radio.

Len Harris’s AWA Teleradio 3C was charged by a Briggs and Stratton petrol engine. It was enough simply to fill the petrol tank once a week and run the engine dry, so operators in remote locations did not need huge petrol supplies. A single 44-gallon drum lasted some months. There were two 12 volt wet batteries which stored enough power to send and receive messages for a week. Compared to the old pedal radio, the range of the new teleradio was remarkable.

I was instructed to send out a general call next morning, like I used to with the pedal radio and see how well I was received. Of course they were expecting my call at VID Darwin Coast Radio. They were to be my new regular radio contact, instead of the medical radio in Cloncurry, so they replied almost instantly. I spoke to the operator, Lou Cornock, in Darwin for a bit and then Thursday Island came on air and told me they were receiving me loud and clear. Then to my great surprise, I got a message from South Australia saying my signal was strong even down there. I had arrived in the world of radio!

We all knew things were getting serious now. I rapidly learned how to use the Playfair Code. Some of our communications were by voice but anything we thought strategically important was coded. Listening to everybody on the radio, I sensed an apprehension. Nobody knew what was going to happen and although people did not admit to being nervous, it was a kind of unspoken truth between us. We all knew there had to be a reason why the Navy suddenly thought us Coastwatchers were important.

The War comes to North Australia

Naval Intelligence Division’s fears of the possibility of Japanese aggression proved more than justified. The Pacific war escalated with frightening rapidity. Bell had not long completed setting up the new Coastwatcher network when, on 19 February 1942, four Japanese aircraft carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryuand Hiryu, 400 km north-west of Darwin, turned towards the wind and began launching 188 planes – 71 dive bombers, 81 medium bombers and 36 Zero fighters.4

At 9.30a.m., Coastwatcher Father John McGrath at the Sacred Heart Catholic Mission on Bathurst Island saw the huge flight pass overhead. Using his newly-issued Teleradio, he contacted VID Darwin Coast Radio. Radio Operator Lou Cornock passed the message immediately to RAAF Operations who received it by 9.37a.m. But the Coastwatcher’s warning was not heeded. As Northern Territory historian, Alan Powell wrote:

Twenty minutes later the first bombs fell on the town. A dismal mix of inexperience, poor inter-service communications, personal antagonisms and plain inertia left the town and the massed shipping without warning.5

On that morning, at least 235 people were killed – Army, Navy and Air Force personnel and many civilians including waterside workers and all the Post Office staff.6Hundreds more were wounded. Twenty aircraft and eight ships including both US and Australian naval vessels were destroyed. Almost all civil and military facilities were rendered inoperable.7

I was at the other end of Grote Eylandt at the flying boat base at Umbakumba on the morning of 19th February. While I was talking to the men there, a radio message came through that Darwin was under attack and that bombs were falling on the harbour and the town. Then the radio went dead. The silence was frightening. ‘It’s taken a direct hit’, we thought. We had no idea what we should do, and imagined we could be the next target. We decided that we would see or hear any Japanese planes approaching and that if we did we would just run and hide in the jungle.

We stayed glued to the silent radio. About two hours later we heard a plane. We ran and hid ourselves away from the buildings. When we saw the plane, it was a flying boat, skimming very low over trees and water. It came down on the lagoon. The officer in charge of the refuelling depot said, ‘Well, padre, now we have a problem! Who is flying the plane? Them or us?’ He knew the crew couldn’t get ashore without swimming. So he got a loaded rifle and took the launch out, staying at a distance. Brave of him, nevertheless. After a while the door opened and the pilot called out. It was obviously an Australian pilot and there was a flight steward with him.

When they got him ashore, the pilot said that he thought he couldn’t just hide and do nothing with Darwin being destroyed around him. He managed to locate another crew member and they found a rowing boat and rowed out through the burning harbour to a flying boat which somehow had not been hit. The engine had started straight away, he said, and they simply taxied through the burning ships, found clear water and managed to take off. They flew low, almost touching the tree tops all the way, he said, expecting to be shot down any moment.8

There was still no radio contact with Darwin but I was a Coastwatcher after all so I decided I should head back to the mission in case I had to be near my radio. The next day radio communication was restored. I found out from Father John McGrath that he had in fact reported the Japanese planes flying over the Bathurst Island Mission. It was all a tragic irony really. The Navy set up a Coastwatching network and then the one time they really needed it, the people in charge in Darwin ignored it. It worked perfectly but they didn’t believe their own system. Father John was a good, intelligent man and Lou Cornock was totally dedicated and efficient. They were just ignored. There could have been far fewer lives lost.

Around Groote Eylandt there was suddenly a marked increase in Japanese activity to report. It seemed to Harris that the Japanese were exploiting the temporary disarray in Australia to venture more boldly into Australian territory. Japanese planes became a daily observation although they were mostly flying very high. Harris identified most of them as Zero fighters, no doubt from Japanese aircraft carriers to the north. There were Japanese ships in the Gulf too, not only fishing vessels but naval ships taking advantage of the period when the Australian Defence Forces were preoccupied. There were more than 60 subsequent attacks on the Australian mainland including the awful carnage in Broome.

It was always possible that Groote could have been attacked. I actually thought it quite likely. The Japanese spies on the fishing boats must have known about the Emerald River Mission for decades and all the other isolated Missions as well of course. But now we had two mile-long landing strips right next to the mission. I thought it was like painting a target on us really. The Japanese planes flying high overhead must have regularly seen the airfield and the mission buildings nearby.

Every now and then the Aboriginal men would get smoke signals relayed from the coastal people telling of the sighting of a Japanese ship between Groote and the mainland. That didn’t surprise me at all. Their fishing luggers had always been hanging around that area before the war. Even then I had wondered why they were checking out the Roper River. It was navigable right up past the Roper River Mission and I know there were naval officers on them. I felt certain that the Japanese after destroying Darwin were now thinking about cutting off the north at the Roper River.

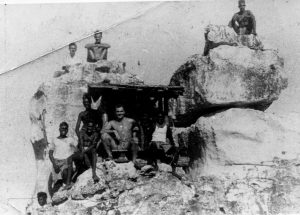

The first ship I actually saw for myself came between Groote and nearby Bickerton Island. Aboriginal people first saw it and alerted us. I went straight away and reported it and then climbed Castle Rock to see for myself. It was a small ship but through binoculars obviously a naval vessel, an armed vessel. Next day, on the radio schedule I got to talk to a senior officer. He said the information was important and had been put out to Navy and Air Force Intelligence but that they couldn’t do anything about it at this point. They had no planes available since so many had been destroyed.

Groote Eylandt was now in a war zone and came within the emergency powers of the North Western Area Command. One of the most complex issues to deal with was the presence of civilians and how to ensure their safety. Many civilians in Darwin itself had already fled. CMS was officially advised by the Department of Army that they could not guarantee the security of the northern missions. Shortly after the bombing of Darwin, a decision was made to evacuate women and children from the north to Adelaide, Sydney and other southern cities. The Qantas refuelling base was placed under Air Force control. Len Harris’s wife Margarita (Margery) and their young son, John, (the author) were evacuated from there in a flying boat carrying wounded servicemen which had come down for refuelling at Umbakumba.

A far more complex issue was the fate of the half-caste women and children. Harris feared for their safety in a Japanese invasion. They were all light- skinned, English-speaking people who would simply be presumed to be Europeans. It was possible that the Japanese might leave Aboriginal people alone but no such guarantee could be made about the light-skinned people. North Western Area Command agreed and ordered the evacuation of the half-caste women and children from the island and coastal missions but, over-stretched already, they were not able to offer a great deal of support.

The women and children, under the care of three amazingly dedicated missionary women, were taken by boat to the Roper River Mission and from there all the way to Sydney on the back of a truck. North Western Area Command eventually provided some limited material assistance but it was a long and arduous journey. They had no real idea where they were going and the evacuees mostly slept by the side of the road. One of the babies died on the way. This whole operation is now controversial and the author has provided details elsewhere.9It was however the only responsible and compassionate option achievable at the time. What some modern critics fail to understand is that this was wartime and that responsible people were quite rightly afraid for the safety of others. They had to make the best decisions they could under great pressure and then act on those decisions without much material support. In retrospect it is easy to look back and say that the Japanese did not invade and that the war ended in 1945. No one knew that then. No one knew that an Atomic Bomb existed.

We had no idea when it would end. I thought it would go on for another ten years at least. So did all the Air Force and Army men I met. I did not think the Japanese forces could get as far as Sydney or Melbourne but I expected they could well take the north. I know there were official contingency plans to fall back south and give up our part of the Territory. I often wonder what would have happened to me if they did.

CMS had taken the hard but patriotic decision to keep the missions open with minimal staff and not ‘desert their post’. Len Harris volunteered to stay on alone at the Emerald River Mission, aware of his responsibility to the Aboriginal people who very much needed the care the mission provided but he was conscious also of the oath he had taken to serve as a Coastwatcher. He later wrote, ‘I am not afraid of being in a War Zone. God is greater than the Japs and I am quite at peace with him in this matter.’10

With Australian Defence resources stretched to the limit, the Japanese seemed to know that they could continue to risk sending small naval vessels into the Gulf. Before the war, the closest to the mission Harris ever saw fishing luggers was when they anchored off Bickerton Island, one of their favourite watering places and less than 20 km from Groote. Harris set up an observation post at the top of Castle Rock and it was manned throughout the daylight hours by Harris or his Aboriginal friends. The Japanese naval vessels still seemed interested in Bickerton Island. Harris wondered if they had something hidden there but if they did, the Aboriginal people never found it.

One evening an excited group of men paddled across from Bickerton to report that numbers of Japanese had actually landed there. I tried to send a coded message straight away but it didn’t get through – I don’t think VID Darwin was tuned to our frequency that night. So I had to wait until next morning.

That evening, as a result of the Japanese landing so close to the mission, Harris felt that he should openly discuss the possibility of a Japanese invasion with the Aboriginal people. It had been worrying him for some time. He did not want to fail them but he also knew that he should not simply presume upon what their response would be.

The question of where Aboriginal loyalties might lie was being openly discussed at that time. There were irresponsible, scaremongering letters to newspapers but there were also serious official reports. Some Lutheran missionaries of German descent were incarcerated during the War and there were concerns that Aboriginal people from the Lutheran missions in Central Australia may have been sympathetic to the Germans and therefore to the Japanese. There were also concerns being voiced that those Aboriginal people who had reason to feel they had been treated unjustly could think that life might be better under the Japanese. And there were concerns that traditional Aboriginal people, living in remote parts of Australia and knowing nothing of the War, might simply see the Japanese as a another intruder but perhaps one with whom to co-operate as a source of desirable goods.

This question of Aboriginal loyalty during WWII has been fully discussed in Robert Hall’s excellently researched book, The Black Diggers.11After canvassing all aspects of the issue, Hall draws the clear and now obvious conclusion that most of those fears were irrational and can now be seen to have had little or no real support in the hearts and minds of the vast majority of Aboriginal people. At the same time as doubts were being aired about Aboriginal loyalty, Aboriginal men were being enlisted to fight for their country. Their courage and self-sacrifice speaks for itself. Many were killed but the sad reality is that those who survived returned to a still racially divided Australia where they had fewer rights than they had experienced in the armed forces.

Harris had absolutely no fears for his own safety at the hands of the Groote Eylandt Aboriginal people, whom he knew as friends but he knew they did not really comprehend the scale of a Japanese invasion and what it would mean to them. He realised that he needed to be proactive, raise the subject and begin an informed discussion in which they could consider how they should act.

‘I thought the discussion would be best in their space, not mine, so I took some flour and tea and sugar down to their campsite. I got the old men together, the decision-makers, Groote men and Bickerton men too, the ones who had come across with news of the Japanese landing.12We sent the small boys for a few more sticks of wood, stoked up the fire, made damper on a hot rock and boiled the billy. Then I broached the subject. My Anindilyakwa was a bit inadequate for such a serious topic but with a bit of English thrown in I managed as best I could. ‘The Japanese might come with all their ships and guns and fighting men’, I said. ‘They might come here and take this country, take Groote Eylandt. Maybe you might be better off with the Japanese than the white people. They might give you more things, more cloth, more knives, more tobacco, more tucker…’

There was much more I had planned to say but they cut me off. They had understood everything – brilliant linguists they are, speaking multiple languages. They talked together earnestly and excitedly, using two languages among themselves, Anindilyakwa and Nunggubuyu, and I got a bit lost. They chose one spokesman and when I didn’t catch on here and there they enlisted the help of the small boys who had learned some English when the school was operating. They too argued among themselves about the correct English and the whole thing would have been quite hilarious if the subject wasn’t so serious.

‘Many people came here in the past,’ they told me. ‘We used to trade with the Maccassans every monsoon season – axes, buckets, cloth, tobacco, grog – but they never stayed on, just gathering trepang until the monsoon winds took them home. Some of our old men went to Maccassar as crew on the prahus when they were young and can still speak that language. The Maccassans didn’t come any more but then the Japanese started coming in their fishing luggers. We could see they weren’t always fishing but snooping around and we were always suspicious of them. But yes, we did trade with them sometimes, exchanging pearl shell and trochus for cloth or tobacco.’

‘The Japanese interfered with our women too,’ they said. ‘Some of the women went willingly to them to sell themselves for tobacco, especially over on the coast, but many were taken by force and some were hurt or even killed’. They stressed to me that the killings were never here but on the coast at Blue Mud Bay and Caledon Bay. ‘On Groote we always protect our women and girls’, they explained. ‘We hide them we don’t let any stranger go near them’.

‘Yes’, I said. ‘I heard that you even used to hide the women and children from the first missionaries!’ They laughed at that. ‘Yes’, they said. ‘We used to hide them before until we learned that the missionaries were good people and wouldn’t hurt them’.

‘The Japanese just came to take what they wanted and went away again’, they said. ‘They didn’t care about us. The only people who ever cared about us were you missionaries. You came and you brought medicine and you helped the children. And you brought tucker like this tea and damper’. They all laughed at that. ‘And what’s more’, they said. ‘You missionaries stayed on and lived with us on our land. You let us see your wives and children and you showed no fear and you trusted us. So if there is any fighting, we are on your side!’

This was the outcome Harris had expected but the words needed to have been spoken and he was glad that he had taken the initiative to bring the question out in the open. Unlike most Aboriginal people across the continent, the Gulf people at least had some history of contact with the Japanese, experience of the Japanese fishing boats and crew and therefore a context in which to consider their response to the war. But there was now a second, personal question on which Harris genuinely wanted their advice. What should he himself do?

I said, ‘Well that’s great but what about me. Right now armed Japanese are just over there on Bickerton Island. What if they come over here tonight? What are we going to do?’ They said, ‘Don’t you worry about anything. You just go home and go to sleep. We know what to do’. I trusted them and I felt safe in their care.

The Aboriginal people knew how to organise themselves quickly if they had to. They sent the women, children and frail elderly people away to one of their secret places to hide for the night. They mustered all the warriors, about 40 armed men in all. They had shovel-nose spears, man-spears tipped with iron, three spears to a man. They posted lookouts on the beach and at the mouth of the river and along the road up to the mission. There was no other way, especially at night, with swamp and jungle blocking any other access to the mission.

The warriors hid behind rocks and big trees all along the track to the mission, hoping to ambush the Japanese, ready in typical Aboriginal fashion for the silent spear in the dark and the quick escape into the jungle. I slept very soundly, actually. I don’t think I had realised how worried I had been about everything and having had that discussion was all a great load off my mind. Nothing happened of course. The Japanese left Bickerton under cover of darkness but we were not to know that then. They could easily have intended to come over to Groote and it was essential that we should have had a plan. I sensed that the Aboriginal men were a bit disappointed really.

In the morning I reported the Japanese landing on Bickerton on the radio schedule. The radio operator, Lou Cornock, got the Navy duty officer to come to the radio. He thanked me and said the information would be passed on but that there was nothing they could do about it. I said, ‘Well, what if they do land on Groote one day? What if the mission is really threatened?’ ‘Listen, padre,’ he said, ‘No heroics now! If there’s ever any kind of imminent danger, put an axe through the radio and go bush!’

My Aboriginal friends had worked that out already! ‘You get us an empty petrol drum’, they said. ‘The young men can take it and hide it near Central Hill and you can live in one of the caves there. We’ll keep it full of water and bring plenty tucker for you. The Japanese wouldn’t find you there and we’d never tell them either.’ I certainly didn’t need any more reassurance of their loyalty and friendship.

Harris continued to observe and report Japanese planes and naval vessels. His informal network of Aboriginal observers and the use of smoke signals extended his observation area all the way to the coast. He heard of the crews of Japanese naval vessels trying to get information from Aboriginal people on the western Gulf coast.

An Aboriginal family were camped at the mouth of the Roper River, fishing by day and sleeping behind the beach at night. One morning they paddled their canoe out early to Maria Island, halfway between the Roper mouth and the Limnen mouth. Beyond the island they were surprised to see a ship. The young men paddled out to investigate. As they got closer to the ship they recognised the writing as Japanese, the kind of writing which they were accustomed to seeing on the Japanese luggers. ‘This is an enemy ship!’ they said to each other. At first they didn’t want to go closer but then they were spotted by a crew member who went and got someone whom the young men took to be the Captain. He called out to them in English and began tossing things overboard for them. Intrigued, they went closer and retrieved tins of tobacco and other goods in watertight containers. The Captain kept beckoning them closer so they paddled up to the ship.

‘Where’s the Roper River Mission?’ he asked them. They kept their cool and betrayed nothing. ‘We don’t know’, they replied. ‘We don’t know about any mission.’ The captain threw them more things and they came even closer. ‘This is the Roper River, isn’t it?’ he asked, pointing to the Roper River delta, north of the island. They lied. ‘You’re too far south’, they said. ‘That’s the Limnen River’. The Captain seemed to believe them because he threw them a few more things and went away and the ship sailed off to the north and never came back. We owe Aboriginal people more than we realise.13

With major Air Force bases in Darwin and Townsville, the North West Area Command began to recognise the potential strategic value of basing a small permanent Air Force unit on Groote Eylandt in the event of a Japanese attempt to take North Australia. There was a need for more than the little refuelling depot with a staff of only two.

The top man himself flew out to investigate, Group Captain Fred Scherger. He was later knighted, I heard, and became Chief of the Air Force.14He was a friendly enough bloke, I thought. ‘Sherg’ the men used to call him. He certainly got things going. He told me that we had built an excellent airstrip and that they wouldn’t need to do much to it to start with. They built more huts and brought in a lot of equipment. There were about 30 men there at times – not just Air Force, but Army and Navy too. Planes began to fly in and out regularly, much to the interest of the locals. I don’t know why they didn’t have a proper radio but I used to have to send and receive messages for them for quite a long time.

Funny thing was, they covered all the Air Force huts and equipment with webbing, camouflage material, while only a quarter of a mile away there we were with a bright white-painted roof which they never tried to disguise during the war. It was like beacon! Pilots could use it to locate the airfield, even at night. My friend the Flying Doctor, Clyde Fenton, had been drafted into the Air Force, no doubt because of his great local knowledge. He often landed at the airfield and came over for a cuppa and he said that he could always find the Groote aerodrome because the white roof of the mission house shone in the moonlight. He said that on really dark nights he had a powerful torch and he could hold it out the window and locate the roof and land safely.

The Japanese attacked Australia and Australian coastal shipping nearly 100 times between February 1942 and November 1943.15But from Harris’s point of view, Japanese activity in and over the Gulf had begun to diminish rapidly, due no doubt to the permanent Air Force presence on Groote Eylandt and the increased aircraft presence in the Gulf. The northern coast was also being patrolled now by members of Donald Thomson’s Aboriginal corps, the Special Reconnaissance Unit.16Harris began to find that his role as an active Coastwatcher was becoming less necessary. It was not that the war was scaling down, far from it. It is often forgotten that no-one knew that atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki would abruptly end the war. As far as Harris was concerned, the war was going to drag on into the 1950s. Rather, the new reality for him was that his official radio work was now almost all on behalf of the Air Force and rarely the reporting of his own observations of enemy activity. He was more than willing to continue if he were needed as a Coastwatcher but he also wanted to carry out his missionary work. He wanted to devote more time to translating the Bible into the Nunggubuyu language. He was very conscious that he was the only priest between the three CMS missions at Groote Eylandt, Roper River (now Ngukurr) and Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya). He longed to travel between the missions in his capacity as a minister but felt loyally tied to his Coastwatcher role.

CMS shared Harris’s views and certainly encouraged him to resume his religious duties. As early as March 1942, when CMS became aware of the upgrading of the Groote Eylandt aerodrome by the Air Force, they approached the Navy to ask about Harris’s status and how necessary it was for him to continue as a Coastwatcher.17It was then agreed that the Teleradio would in due course be handed over to the Air Force and Harris would be free to leave his Coastwatcher post. As it happened, this did not physically take place until much later in 1942 but by the beginning of 1943, when CMS was able to appoint another missionary to Groote Eylandt, Harris was freed to take up the role he so much wanted to fulfil, translating the Bible and travelling between the missions.

The strange thing is it was in some ways just as dangerous a job. I suppose the RAAF base on Groote Eylandt may have made Emerald River Mission a potential target but coastal travel was particularly dangerous. I travelled a lot by boat and in the mission lugger. In January 1943 my friend and fellow-Coastwatcher Leonard Kentish from the Methodist Mission on Goulburn Island was taken by the Japanese. He was travelling on a boat between missions. Near Elcho Island the boat he was in was bombed by the Japanese. He survived that, only to be taken from the sea by a Japanese float plane and never seen again. We did not find out until after the war that Len had been tortured and beheaded. I think he was the only Australian ever taken prisoner within Australia itself.18

Was I ever frightened? Well of course I was, particularly when Darwin was first bombed and I felt so isolated on Groote. But never will I ever forget the loyalty and care of my Groote Eylandt Aboriginal friends. They were great people and I don’t think Groote Eylandt will ever see their like again.

I am proud to have made some small contribution as a Coastwatcher. In retrospect I now see that the real dangers we feared never actually eventuated but we did not know that then. We thought the war could go on for ten more years! From our perspective as it was then, I accepted that there was a risk. I chose the role and I expected that I could have been killed or taken by the Japanese. But so many Australians gave their lives. It was the least I could do. I never hesitated for a moment. It was simply a question of duty.

Later recognition of Len Harris’s service

Len Harris returned to Sydney in 1946 where he spent the rest of his life in ministry in the Church of England (Anglican) Diocese of Sydney. His first appointment was as Rector of Blacktown. He took an immediate interest in the nearby Schofields Air Force Base. In 1948 he became Chaplain to the Schofields and Richmond Air Force Bases with the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

Some time afterwards he heard from missionary colleagues in New Guinea that missionary Coastwatchers whom they knew there had been commissioned as Navy Lieutenants and given Navy insignia. This was in the vain hope that a rank might give them better treatment if captured by the Japanese.19

I did wonder about that! I did swear an oath of loyalty administered by the captain of a naval vessel in time of war. I can’t quite remember what the exact words were but I have always presumed that I simply became an official Coastwatcher. But now I have the rank of Flight Lieutenant anyway so it hardly matters what I was back then!

In the 1970s, Harris’s wife, Margarita, became unwell so he sought out a quieter life for them both by taking a part-time appointment as Priest in Charge of St Georges, Gerringong on the NSW south coast. His salary was hardly enough to live on, so a friend suggested to him that he might be eligible for a Service Pension through the Repatriation Department (now the Department of Veterans Affairs).

I was a little bemused at this at first. It had never really occurred to me that I would be eligible for benefits like that. But if other Coastwatchers had Navy rank, perhaps I might be eligible for something. So I thought, well, why not give it a go.

Harris began the process of seeking a Service Pension in March 1973. The question of his eligibility was considered at the highest levels in the Repatriation Department and Department of the Navy. It was determined that while he had not actually been commissioned as a naval officer, he had indeed served as a Coastwatcher. One of the problems was that in any of the restricted or secret documents in which his name might have been mentioned, it was suppressed and he was referred to, if at all, only as ‘the Missioner’. However after investigations which took six months, Harris was granted a pension in November 1973. Len Harris died on 28 September 1988.

The research on which this paper is based commenced in 2009. Discovering any information regarding the determination that Len Harris received a pension proved very difficult. The Department of Veterans Affairs, while acknowledging that Harris had indeed received a Veterans Affairs Pension, told the author that no file on him now existed. They did however provide what they said used to be his file number, AG489. It was the prefix which finally solved the problem. AG stands for Act of Grace. Harris’s pension was an Act of Grace, accorded to those who had in fact served as if they were in the armed forces but had not strictly been members. The National Australian Archives was initially unable to locate such a file. It was not for some years that an assiduous staff member came across a box of Act of Grace files and remembered the author’s search. Len Harris’s file AG48920was among them and in due course was cleared and released.

The Department of the Navy’s advice to the Commissioner for Repatriation was as follows:

Reverend Len Harris was not a member of the Commonwealth Naval Forces.Records held in this office indicate that the Missioner in Charge, Groote Eylandt (Church Missionary Society) acted as a Coastwatcher. He was issued with a teleradio and Playfair Code for use in carrying out these duties.21

The Department of Repatriation contacted CMS who confirmed that the ‘Missioner in Charge’ was in fact Len Harris, that he had served as a Coastwatcher, and that Commander R.B.M. Long had sought CMS’s consent for the installation of the teleradio at the mission. Finally, the Department of Repatriation advised the Treasury to grant the pension.

The Commission considers that, having regard to the circumstances of the case, and to the precedent that exists for ex gratia payments to former coast watchers, Mr. Harris has a moral entitlement to consideration under the Repatriation Act as if his service on Groote Eylandt at the relevant time had been as ‘a member of the forces’. The Commission therefore seeks approval for payment to him, as an Act of Grace, of any benefit by way of service pension (and supplementary assistance if appropriate) that he could be paid if he were ‘a member of the forces’.22

The Treasury approved the pension on 14 November 1973. He had deserved that small recognition. Perhaps the last words are due to the Reverend Len Harris: it was simply a matter of duty.

1 Leonard John Harris, 16 November 1911 – 28 September 1988 was ordained an Anglican priest on 13 February 1938 and married Margarita Morgan on 18 February 1939 just before taking up his appointment as chaplain at the Church Missionary Society, Emerald River Mission on Groote Eylandt, NT.

2 Naval Historical Review, Vol 37, No 1, March 2016.

3 The Playfair Code or Playfair Cipher used an easily drawn grid in which the letters of the alphabet were arranged on the basis of a code word. A suitable code for the Coastwatchers, it required only a pencil and paper to encode and decipher. At that time it was a hard code to break without the secret code word and was therefore useful for encoding messages which had short term importance and were useless to the enemy by the time they had decoded them.

4 Alan Powell, Far Country, Melbourne University Press, 2000, pp192-3

5 Powell, p193

6 The precise number of dead may never be known. 243 was for a long time the accepted figure and there is memorial plaque in Darwin saying 291 were killed. The best and most recent research suggests a figure of 235. See Tom Lewis and Peter Ingram, 2013, Carrier Attack, Kent Town, SA: Avonmore Books.

7 http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs195.aspx

8 An historical note on the Qantas website reads, ‘A Qantas crew saved an Empire flying boat near a burning munition ship in Darwin Harbour, taking off moments before the 11,000 tonne ‘Neptuna’ exploded with such force that the stern landed the other side of the wharf.’ http://www.qantas.com.au/travel/airlines/history-world-at-war/global/en

9 John Harris, 1998, We Wish We’d Done More, Adelaide:Open Book Publishers, pp 405-417

10Len Harris to John Ferrier, CMS, 14 May 1943. Copy in Harris’s papers.

11Robert Hall, 1997, Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders and the Second World War, Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press. See particularly Chapter 6.

12The Aboriginal elders present included Old Charlie Galiawa (old Charlie), Nagwaraba (Banjo), Diamandu and Noa-noa (Mick). (Names as Len Harris spelled them).

13This version of the story is as Len Harris recalled it. The story was often told in later years at Roper River (Ngukurr) by Old Agnes. The two young men were named as Isaac and Joshua. A recording and full transcript of Agnes telling the story are in the possession of the author.

14Air Chief MarshalSir Frederick Rudolph William Scherger, KBE, CB, DSO, AFC(18 May 1904 – 16 January 1984) served as Chief of the Air Stafffrom 1957 until 1961, and as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, forerunner of the role of Australia’s Chief of the Defence Force, from 1961 until 1966. He was the first RAAF officer to hold the rank of Air Chief Marshal.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Frederick_Scherger

15 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_raids_ on_Australia_1942–43

16Two Australian anthropologists, familiar with Aboriginal people, were appointed to lead two specialised observer units. Flight Lieutenant Donald Thomson’s Special Reconnaissance Unit patrolled the coastal waters and worked with Aboriginal observers on the coast and islands (although the Aboriginal people’s service was not recognised until 1992). On the mainland Major William Stanner’s North Australia Observer unit also included considerable numbers of Aboriginal people.

17NAA. Teleradio – Groote Island, Series No B3476, Control Symbol 133, Barcode 509101

18For Kentish’s story see http://www.artsandmuseums.nt.gov.au/northern-territory-library/the-territorys-story/territory_characters#LenKentishFor the sinking of the Patricia Cam, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Patricia_Cam

19After the capture, torture and murder of Percy Good, an elderly copra planter on Buka Island, off Bougainville, all civilian Coastwatchers were enlisted into the RAN in the probably naïve belief that their officer status would protect them if they were captured by the enemy. http://www.ww2australia.gov.au/coastwatcher/. Also http://www.battleforaustralia.org/Theyalsoserved/Coastwatchers/CoastwatcherRole.html.

20NAA, File AG489: HARRIS, Leonard John, Series No A2806, Control Symbol, AG489, Barcode 13600061.

21Memorandum, Dept of Navy to Deputy Commissioner of Repatriation, Sydney, 3.07.73, in file AG489.

22Secretary, Repatriation Commission to Secretary, Department of the Treasury, 29 August 1973, in file AG489