- Author

- Linton, E.W. (Jake), BEM, MCD, Commander, RAN (Rtd)

- Subjects

- RAN operations, Post WWII

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Hector Donohue and Jake Linton

The following article describes the first swimmer/sapper attack involving CDT3 in Vietnam and is drawn mainly from the recently published book United and Undaunted – the First 100 Years, by E.W. Linton and H.J. Donohue. It also includes data from the Australian War Memorial archives covering intelligence reports on the incident based on interrogation of the two enemy sappers captured. Additionally, interviews were conducted with John Brumley, Jeff Garrett and Mike Ey, the three surviving members of the team.

Background

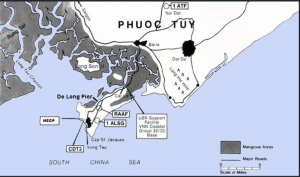

In the early hours of 23 May 1969 a swimmer/sapper attack against ships berthed at the DeLong pier in Vung Tau was thwarted, with Clearance Diving Team 3 (CDT 3) playing a major role in the incident including the recovery of two modern Soviet BPM-2 limpet mines. The RAN’s CDT 3, based in Vung Tau was integrated into the USN EOD Mobile Unit Pacific (EODMUPAC) organisation in South Vietnam and designated by the US as EODMUPAC Team 35.

Navy EOD detachments were deployed to key areas throughout Vietnam to contribute to the overall defence of shipping in ports and rivers under Operation Stable Door. EOD support was also required for all the major shore-based facilities and ports, and to undertake an ever increasing demand for Navy EOD to support land-based Army and Marine Corps units.

With the building of a DeLong mobile pier, Vung Tau had become a major support base. Capable of offloading deepwater and shallow berth vessels, Vung Tau increased the flow of logistics throughout South Vietnam. Patented by the DeLong Corporation, the piers were sectional and were fabricated in a variety of sizes and configurations. They were then towed to a site and quickly emplaced.

(The DeLong piers made it possible to develop deep-draft ports and berths at Qui Nhon, Vung Tau, Cam Rahn Bay, Vung Ro, and Da Nang in a few months.)

North Vietnamese sappers were assault or shock troops, which in today’s parlance would be designated as Special Forces. Naval sappers were organized just as other sapper units, the main difference being that naval sappers tended to be less hierarchical and more centralized and flexible in their organization. Naval sapper targets included commercial and military shipping, bridges, and piers, floating military bases, shore bases, power plants, and any other target that was close to water. Within a naval sapper platoon, there were generally two combat groups of two to five men. It was known at the time that Group 10 VC, reinforced by 126 North Vietnamese Navy Regiment Sapper Swimmers, was based somewhere in the Rung Sat Special Zone, near Vung Tau.

A favoured method of swimmer insertion was from a sampan. Sampans were the most common waterborne vessel in Vietnam and so were the perfect covert insertion vehicle for the swimmer. The sampan allowed the swimmer to extend his range from the main base and carry more or heavier gear. Sampans also blended in with ‘normal’ waterway traffic which made them the perfect reconnaissance platform for the swimmer.

A US Navy study calculated that there were 88 successful swimmer/sapper attacks against shipping in Vietnamese waters between January 1962 and June 1969 which killed more than 210 personnel and wounded 325. Against this only 20 enemy sappers were killed or captured for all attacks, whether successful or not, emphasising the extremely advantageous payoff to the enemy of this type of attack.

The Attack

On the night of 22/23 May, under cover of darkness, a motorised sampan conducted a reconnaissance before dropping three swimmer sappers near the DeLong pier in Vung Tau harbour. The prior reconnaissance by the sampan established the port’s master lighting system was no problem and the sappers could swim to their objective without passing through an illuminated area. They observed sentry positions and patrol boat patterns.

The sappers waited until slack tide conditions and three left the sampan, two with limpet mines and one with a locally made explosive charge. They swam towards the ships alongside the pier on the surface. They were not concerned with the possibility of small arms fire or underwater explosions since their reconnaissance indicated that the sentries did not shoot at floating debris nor were grenades being used to any degree. On the night the moon was a waning crescent giving enough light for a swimmer to see his objective but still remain relatively unobserved by a sentry.

At around 0125, a sentry onboard USS Hickman County (LST – 825) spotted two swimmers 75 yards astern moving in a northerly direction with the incoming tide. The sentry opened fire with small arms as the swimmers headed for the pier in the vicinity of MV Heredia, which was berthed alongside the northern end. Two converted tankers were at permanent moorings just south of the piers which were potentially lucrative targets as they supplied electrical power for all the military installations and some civilian assets in Vung Tau and surrounding areas. However, on this occasion, Heredia, an ammunition ship, would have been the target as the ship was carrying almost 8,000 tons of explosives.

Hickman County’s sentries then saw three swimmers with packages and opened fire again, while the ship, now alert to the attack, increased readiness and called for EOD assistance. Two swimmers struck south towards the hard stand and anti–swimmer lights and signal lights were shone on them. Concussion grenades were thrown into the water. The ship notified port control via radio, and army MPs arrived to investigate the shooting. The two swimmers were by now 150 yards to starboard heading towards the hard stand. A patrol boat pursued the swimmers and came within the line of fire preventing further firing from the ship. Contact with the swimmers from Hickman County was lost but one swimmer was captured by the patrol boat.

CDT 3 Response

Two team members, POCD John Brumley and ABCD Andy Sherlock, had left the team’s headquarters (and accommodation) at the Harbour Entrance Control Post (HECP) to conduct a routine search of ship’s anchor cables in the anchorage off Vung Tau under Operation Stable Door. Lieutenant ‘Snow’ Davis, OIC of the team, was temporarily absent in the Delta area.

At 0130 a phone call was received at the HECP stating that swimmers had been positively sighted in the water off the end of the DeLong Pier. Within 15 minutes, the remaining team members, CPOCD Vic Rashleigh, ABCD Jeff Garrett and ABCD Mike Ey, arrived at the DeLong Pier. They found the area around the pier and ships in turmoil. US MPs were shooting at random and throwing grenades and scare charges off the pier. Rashleigh managed to restore order and ordered the pier cleared of all but MPs and EOD personnel. It was learned that one swimmer had been captured and a nylon rope was visible, attached to a large tractor tyre fender close to Heredia.

Rashleigh decided to put a diver in the water to investigate. Security personnel were informed that diving would commence and use of scare charges and grenades were suspended. Well aware that enemy sappers were close, Garrett dived under the fender to discover a locally made explosive charge the size of a four gallon drum, fitted with a wire strop to which was attached to a nylon line. The line was tied to the fender and the mine suspended about 12 feet below the surface. The other two pulled him out of the water and back onto the wharf.

On being briefed by Garrett, Rashleigh advised the MPs to clear the area of all personnel and the master of Heredia was also advised to move his ship as soon as possible. As preparations were made to move the ship, a small explosion was heard. Rashleigh checked to see if grenades had been thrown in the water and on receiving a negative response, told Ey to investigate the charge. Ey entered the water from the bows of a patrol boat positioned between the ship’s stern and the wharf and found the mine had experienced a partial detonation which would have been the small explosion they heard. The container bottom was burst open and he recovered some of the contents which appeared to be plastic explosive.

Brumley and Sherlock joined the operation around 0230. Having heard of the attack, they cancelled the Stable Door ship inspections they were due to carry out approximately three miles distant in the anchorage. The team commenced searching the entire pier structure and other vessels alongside the southern side of the pier.

At 0310 Heredia was moved and the explosive charge attached to the pier was lifted clear of the water and onto the roadway. On inspection it was found the booster charges were badly packed in US jam tins and had not detonated. The enemy had reached the target but were let down by a poor product. The bulk explosive was some 60 pounds of C4 plastic explosive and the booster consisted of ten pounds of cast TNT. The charge failed due to poor selection of detonator/booster combination i.e. the detonator was ineffective and or the booster was too stable to maintain the detonation wave into the bulk explosive.

The captured swimmer was interrogated by an interpreter about the presence of other swimmers but admitted nothing. Around 0400, there was a further outbreak of shooting by MPs on the pier and a second swimmer was apprehended. He was a North Vietnamese sapper who had been wounded in the earlier shooting was found holding on to one of the piers, hoping to remain unseen in the darkness.

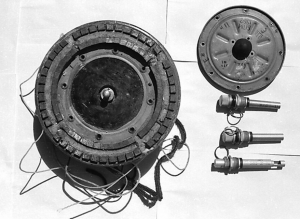

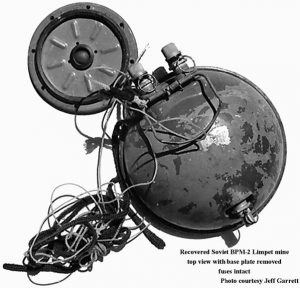

At dawn the team returned to the HECP to recharge diving equipment and returned around 0900. A sentry reported seeing a swimmer earlier near a large steel fender on the northern side of the pier in the vicinity of where Heredia had been berthed. Ey dived in and found a Soviet BPM-2 limpet mine attached to the fender’s underside. Visibility was poor but he could see the arming forks were still intact on the dual firing fuses but not if the safety pin was also intact on the anti–removal device fuse. A rubber flotation bag, still inflated, was strapped to the mine. He secured a rope to the limpet mine’s carry handle and the patrol boat attempted to pull the mine free but the rope parted. Ey dived again to the mine and was able to see that the third pin was in place. He pulled the mine off the fender and surfaced at the stern of the patrol boat. The limpet mine was taken onboard and made safe by removing the three fuses.

Impact of the Attack

The swimmer sapper attack had been well planned. It was believed the group had been in the general area since December and certainly their reconnaissance on the night of 22/23 May indicated that they had a good chance of success. Fortunately, alert sentries during the middle watch sighted the swimmers and thwarted the attack of the two carrying limpet mines. One sapper had reached his target and secured a relatively large charge alongside the ammunition ship. Fortunately it failed to detonate correctly; if it had, it would have resulted in a major disaster. In the event two sappers were captured and the sapper responsible for deploying the locally made charge managed to escape. The overall response to the attack showed that the established doctrine was sound and yet again showed how important alert sentries are.

CDT 3’s rapid response to the call for assistance, arriving on the scene within 15 minutes of a call in the middle of the night, was impressive. CPOCD Rashleigh arrived to find a disorderly situation, made more dangerous as live ordnance was being discharged, and quickly established order, allowing the divers to search for mines. The fact that mines/charges had been deployed, that enemy sappers were still in the area, and working underwater at night with no visibility, made the diving task particularly difficult and hazardous. Garrett and Ey, who no doubt experienced a sense of disquiet that night, performed their tasks professionally and exhibited a high level of bravery.

The recovery of two modern Soviet made limpet mines proved to be valuable intelligence. Although US intelligence was aware of the BPM 2 limpet mine, this was the first time a mint condition mine had been recovered. The CDT 3 team members removed the explosive and together with a USN EOD team member who was with CDT under the Australian and US exchange program, devised a render safe procedure which was both safe and feasible. The previous procedure of sliding a metal shim under the limpet was shown to be completely impracticable and certainly unsafe. One mine was given to the USN by Lieutenant Davis and is held by the Naval Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technology Division Indian head, Maryland, whilst the other was returned to Australia and is at the Diving School, HMAS Penguin.

The senior USN EOD officer from Naval Support Activity, Saigon flew down to congratulate the team on a job well done. Garrett and Ey were recommended for the US Bronze Star but the award could not be accepted because of Australian government policy at the time. CPOCD Vic Rashleigh was awarded the British Empire medal and ABCD Jeff Garrett a Mentioned in Despatches. It is surprising that there has been little recognition of the import of this event, removing a sophisticated limpet mine would in most circumstances merit a significant award. As a result of the attack, the Vung Tau Sub Area Command updated its defence plans, a Joint Tactical Operations Centre was created and Standard Operating Procedures were revised.