- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This is the first of a three part series covering the Australian-Indian relationship.

Australians fought alongside Indian troops in two world wars, but what do we know about them? Both our nations have similar colonial pasts but have taken different paths to self determination. We have not grown particularly close or achieved any cultural level of sophisticated understanding. This is perhaps a pity as India is currently the second most populated country on our planet and is expected to surpass China within the next decade to become the largest. Its industrial base is expanding and will become important economically to the rest of the world. India is therefore on the threshold of becoming one of the most influential of nations, and her decision-making is likely to impact our national defence and control of the Indian Ocean. Looking ahead we may also note that one of the fastest growing migrant groups now calling Australia home come from the Indian Sub Continent.

Colonial Period

Relations with the early Australian colonies and British India were closer over two centuries past than they are today. India, at the very centre of British colonial power, provided administrative and military support over much of central Asia and even into the Pacific. In September 1790, William Grenville, Secretary of State for the Home Department, had written to the Governor-General of India, Lord Cornwallis, saying that a transport of the Third Fleet would be sent to Calcutta to obtain provisions after unloading its convicts in Sydney, as this would be cheaper than supplying New South Wales from England or the Cape of Good Hope. And so when the infant colony of New South Wales, in its fourth year, was starving when the supply ship Guardian sank off the Cape, it was to Calcutta that Governor Phillip turned for aid, dispatching the ship Atlantic to bring back all the food and stores she could carry.On her return voyage Atlantic was the first ship to come to the Colony from India, arriving at Port Jackson on 20 June 1792.

In November 1796, Campbell, Clark & Company of Calcutta sent a ship, which they had renamed Sydney Cove, with a speculative cargo of general merchandise and 7,000 gallons of spirits to Port Jackson. Traversing around the western coast of New Holland the ship encountered severe gales and was wrecked on Preservation Island off the north coast of Van Diemen’s Land. Taking a longboat, three survivors eventually reached Port Jackson and a salvage mission was undertaken to rescue the remainder of her crew plus the valuable cargo. Undeterred by this setback, the company fitted out another ship, the Hunter (named after the then Governor of NSW), with an assortment of Indian goods which arrived in Sydney in June 1798. A representative of the company, Robert Campbell, was so impressed by the trading prospects that he invested in a house and land on the west side of Sydney Cove where he established a wharf and warehouses. On the proceeds of the Australian-Indian trade, Robert Campbell became one of the new colony’s richest merchants.

The aforementioned Sydney Cove adventure was remarkable as the long boat too was wrecked when attempting a landing on what is now southeast Victoria. Her crew then spent nine weeks walking coastal tracks making for Sydney Cove. They were helped by Aboriginal tribes during this ordeal. This is likely to be the first encounter between indigenous people from the Australian continent and the Indian sub-continent, noting that the majority of Sydney Cove’s crew were native Bengalis. This Anglo-Indian seafaring party also established the first overland route between New South Wales and what was to become Victoria.

The first Anglican Church in New South Wales reported through the Bishops of Calcutta. Royal Navy ships in New South Wales waters formed part of the East Indies Station, with its admiral headquartered in a grand residence at Trincomalee, one of the world’s finest deep-water harbours, on the east coast of Ceylon. British regiments serving in the Australian colonies were sent on lengthy commissions of ten or more years which usually rotated between tropical and temperate climates, with temperate NSW being much healthier than disease prone Bengal.

A vivid description of the interaction between colonial NSW and India is found in a wonderful volume by Broadbent, Rickard and Steven (1) which tells us that until 1850 Australia’s most immediate links were with India rather than London, as chaplains, judges, bureaucrats, merchant and convicts moved between the two colonies. By 1840 a ship was leaving for, or arriving at, Sydney from India roughly every four days as Calcutta merchants scrambled to supply and profit from the new outpost. At a price, every form of luxury was available and, in return, NSW supplied coal and ‘walers’ (rugged colonial bred horses) for the Indian Army. In the days of sail the Sydney settlement was very remote from the succour of the mother country, by comparison a voyage to Calcutta was less than half this distance.

Calcutta had grown from being the fortified headquarters of the British East India Company to become the City of Palaces. It was the biggest, richest and most elegant colonial city in the Orient. Australian girls from wealthy families would go to finishing school here, to find suitable husbands without the stain of criminal backgrounds. A stream of retired colonials, some with Anglo-Indian offspring, came to call Australia home.

The Australian colonies underwent an exceptional phase of development following the gold rushes of the 1850s. With this, trade and industry developed, especially with Europe and America, to the detriment of the Australian-Indian relationship which never recovered.

Another small but lasting form of relationship occurred in 1846 when the first Afghan camel was imported as a trial in helping to cross an inhospitable hinterland. This proved successful and in 1860 three Afghan cameleers with 24 of their ‘ships of the desert’ landed in Melbourne to assist in the Burke and Wills expedition. Their offspring (the camels) thrived and are now found in abundance in the outback.

To place India’s importance to the Crown into perspective it is interesting to relate to the words of Lord Curzon, perhaps the greatest of all Viceroys, a brilliant scholar who had travelled widely throughout the East. In 1891, when Parliamentary Under-Secretary for India, he wrote: As long as we rule India, we are the greatest power in the world. If we lose it, we shall drop away to be a third rate power.

The Indian Mutiny

The Indian Mutiny was a rebellion against the rule of the British East India Company (BEIC) which lasted from May 1857 to July 1859 and extended over most of northern parts of the subcontinent. The reasons are many and complex, demonstrating a lack of understanding on both sides, but it arose when native soldiers rebelled against their mainly British officers and resulted in much bloodshed and reprisals. Its conclusion also saw the end of the BEIC and led to a new form of imperial government. The Army was reorganised with an increased ratio of British officers and the artillery was mainly taken back into British hands. Another historically important event was the trial and exile of the last of the once mighty Mughal Emperors, Bahadar Shah Zafar. At this stage Zafar was little more than a nominal Emperor, with most of his lands confiscated by the BEIC and minor princelings. He had however given support to the rebellion which allowed the British authorities to finally end his reign.

The First World War

The borders of the Indian sub-continent have changed dramatically since democratic self rule was proclaimed in 1947. There are the new independent countries of Bangladesh, Myanmar (Burma), Pakistan and Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Others such as Afghanistan, Bhutan and Nepal, if nominally independent in the early 20th century, had to bend to the wishes of the Viceroy.

At the outbreak of WWI the Indian Empire was assumed to include all these nations with borders extending from Persia in the west, to Russia in the north, and Siam in the east. With the southern borders safe within seas controlled by the Royal Navy, the Dutch East Indies were the nearest maritime neighbours. India was strategically and importantly placed between the competing interests of the British and Russian empires.

Herbert Kitchener (2) was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India in 1902 and for the next seven years reformed the Army of India into a force of nine divisions, each division comprising one cavalry and three infantry brigades with one British regiment or battalion serving in each brigade. By 1914 the Indian Army was the largest volunteer force in the world comprising 240,000 men, only just short of the 247,000 men in the British regular army. At this time Australia had a population of 5 million, Great Britain 46 million (including over 4 million Irish), but India could count a multitude of 315 million.

The Indian Army, although of great size, was ill prepared for modern warfare both in training and equipment. Being largely raised for home security, it was unsuited to prolonged campaigns in cold and wet European winters. It did however see action against the German Empire in East Africa and on the European Western Front; Indian forces were sent to China and Egypt, and fought against the Ottoman Empire at Gallipoli and in Mesopotamia. Indians were also garrisoned atAden guarding the Persian Gulf, and watching Burma and the North West frontier. A popular parody of these times contained the following lines:

We don’t want to fight; but, by Jingo, if we do

We won’t go to the front ourselves, but we’ll send the mild Hindoo

There were however problems, mainly of an ethnic and religious nature as the majority of Indian troops were recruited from the more warlike and dominant Muslin northern provinces, while the remainder, and majority, of the country was predominately Hindu. The Muslims, however, were reluctant to be drawn into conflict against their Ottoman cousins. Accordingly, troops at Gallipoli were mainly Ghurkhas and Sikhs.

Australia had about 20,000 mainly volunteer troops at Gallipoli, many with limited experience and training. India had by comparison 15,000 professional troops comprising one infantry brigade, one mountain artillery brigade and a mule transport corps. The 600 men strong Mule Corps with their 1,000 plus mules were said to be the unsung heroes of Gallipoli as without them the Anzacs and many others would not have been able to hold on for as long as they did.

An uprising occurred in February 1915, known as the ‘Singapore Mutiny’, where up to half the 850 strong Indian 5th Light Infantry Regiment mutinied following rumours they were being shipped to the Middle East to fight against fellow Muslims. This regiment had been entrusted with guarding prisoners from the German cruiser Emden recently sunk by HMAS Sydney. The German prisoners did not join the mutiny which was eventually quashed by British forces aided by naval detachments from allied warships. Regardless of these problems, which were relatively minor to overall operations, Britain could not have sustained a campaign of these dimensions during WWI without the aid of Indian troops.

Calcutta fades into Kolkata

Somewhat similar to the Australian experience, in 1911, it was decided to move the national capital from the eastern seaboard city of Calcutta to a central inland site. Work commenced in earnest after WWI withgreat administrative buildings constructed with the new capital of the Raj inaugurated at New Delhi in 1931. Glorious Calcutta, once the second city of the British Empire, and for more than fifty years the second home of many Australian colonists, begins to fade. The city is now known as Kolkata.

Political Instability

Political elections were held during 1936-37 covering eleven Indian provinces which resulted in the Indian National Congress (INC) under Jawahaial Nehru winning power in eight provinces and the remaining three provinces falling to the All-India Muslim League (AIML) under Muhammad Ali Jinnah. After the elections the Muslim League offered to form a coalition with Congress which was rejected in favour of a single majority party government.

The Congress ministers resigned in November 1939, in protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow’s (3) declaration of India as a belligerent in the war against Germany on 3 September 1939, without consulting the Indian people. With the advent of war the stage was set for a political upheaval which would not be resolved until well after the war had ended.

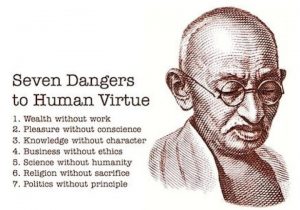

Mahatma Gandhi

No analysis of modern Indian history is complete without mention of that great thorn in the side of officialdom, Mahatma Gandhi, whispering words of wisdom. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) was born to an elite merchant family living on the west coast of India. He was sent to England to study law and after being admitted to the Bar returned home and set up a practice in Bombay. Shortly afterwards he took a post with an Indian company in South Africa where he was to spend the next 21 years. Here he suffered racial discrimination and, became conscious of the great divide between the two classes of Indians; his wealthy Muslim clients and the impoverished Hindu indentured labourers whom he supported.

During the Boer War Gandhi favoured Britain and formed a respected 1,100 strong volunteer Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. But even under British rule there was little improvement in the plight of Indians living in South Africa. His campaign of civil rights advocating nonviolent civil disobedience brought him into conflict with authorities, leading to his imprisonment. However his charismatic charm brought many admirers including the revolutionary Jan Smuts (later Governor-General of South Africa) who visited Gandhi in goal where they discussed philosophy. Before returning to his homeland in 1915 Gandhi was given the honorific title ‘Mahatma’, meaning high-soul or venerable.

Back in India Gandhi set about organising the lower classes in protest against excessive taxes and discrimination. He assumed leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921 and challenged British authority seeking self-rule for the indigenous community. Gandhi led by example, livingly modestly and dressed in simple traditional clothes associated with the poor. Again he was imprisoned as his passive resistance was seen as subversive to the war effort. After attaining his life’s ambition, witnessing self-rule and the tragedy of partition, he was assassinated by a dissident. His gift to humanity was freedom for oppressed people, paid in part by his own martyrdom.

To be continued – Part 2 of this story, mainly covering the important contribution made by Indian forces during WWII when they often fought alongside Australian troops, will be included in the next edition of this magazine.

Notes:

1 Broadbent, James, Rickard, Suzanne & Steven, Margaret, India, China, Australia: Trade and Society 1788-1850, Sydney: Historic Houses Trust NSW, 2003.

2 Field Marshall Lord Horatio Herbert Kitchener, WWISecretary of State for War responsible for recruitment (Your Country Needs You) and material production. He died on 5 June 1916, in HMS Hampshireafter the ship sank on striking a German mine, en route to Russia where he sought to encourage greater participation in the war effort.

3 Victor Alexander John Hope, Marquess of Linlithgow, a well-educated ex-army officer and conservative politician. He was first offered the governor-generalship of Australia but turned this down and in 1936 became Governor-General of India, a position he held until 1943, becoming the longest serving in the history of the Raj. His father, when Earl of Hopetoun, was Governor of Victoria and then the first Governor-General of Australia.