- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Like some sections of our own armed forces who fail to acknowledge a period of colonial rule over which we had no direct control, there are those within the Indian Military Forces who take a similar stance insisting their history began after independence from Britain. But a nation cannot escape its past because of a dislike of some particular era. Part 1 of this series explored the extent of Indian military history until the commencement of the Second World War and we shall now move forward to Independence.

Extent of the Empire

In the period of the Raj before WWII India included Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka with the nominally independent Bhutan, Nepal, Burma and Afghanistan also paying heed to the viceroy. The Empire extended its influence over a huge area and population, with borders extending from Persia in the west, to Russia and China in the north, and Thailand in the east.

India and her associated states provided more than 2.5 million men to fight for the Allies in WWII. Field Marshall Sir Claude Auchinleck, the Commander-in-Chief India from 1943 to 1948, asserted that the British: couldn’t have come through both wars (WWI & WWII) if they hadn’t had the Indian Army. These sentiments were echoed by Field Marshall Sir William Slim (later Governor General of Australia) who said: It was a good day for us when he [Auchinleck] took command of India, our main base, recruiting area and training ground. The Fourteenth Army, from its birth to its final victory, owed much to his unselfish support and never-failing understanding. Without him and what he and the Army of India did for us we could not have existed, let alone conquered.

The Political Situation

Unlike Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa which were all self-governing Dominions within the British Empire, India, the ‘Jewel in the Crown’, remained under colonial rule. India stood at the very centre of the empire and the rise of an independence movement was of much concern to Great Britain. Those in charge had to be selected with great care. From 1936 the viceroy was the Marquis of Linlithgow, a respected, well-educated ex-army officer and Conservative politician. He was relieved in 1943 by Field Marshal Alexander Wavell (later Earl Wavell). Other than for a short period as Commander-in-Chief of the ill-fated Java based ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command) Wavell had been Commander-in-Chief India when he received the rather surprising offer to become viceroy. Although not popular with Churchill, Wavell was seen to be a safe pair of hands to wrest Burma back from Japanese occupation and stabilise unrest. At the end of WWII Wavell was recalled and replaced by the last of the viceroys, Lord Mountbatten.

As Prime Minister, Churchill, was virtually represented in India by Leopold (Leo) Amery, who was Indian born and a contemporary of Churchill’s at Harrow. Amery, a brilliant scholar, could speak Hindi and eight other languages. He became a correspondent for The Timesbefore entering politics and between 1922 and 1924 was First Lord of the Admiralty. Although not always in agreement with Churchill he became Secretary of State for India (1940-1945) and was the power behind the throne to which the viceroy was required to answer.

There were a number of powerful Indians representing the Congress Party including Gandhi (see Part 1), Nehru, Bose and Jinnah. Jawaharlal Nehru was a particularly influential member of a rich Kashmiri Brahman family and another old Harrovian, who completed his education at Cambridge. Mohammed Ali Jinnah was a successful lawyer and shrewd politician known for his efforts in forging compromise between Hindus and Muslims. Jinnah led the powerful Muslim League. Subhas Chandra Bose, who had completed his education at Cambridge, was the enfant terrible of Congress and a charismatic leader capable of stirring the masses. In 1938 he was elected President of the Congress Party.

The size of the Indian armed forces at the outbreak of war in September 1939 was: Army 194,373 men, Air Force one squadron of 285 officers and men and a small naval force with 1,846 personnel. This does not include the Indian Merchant Marine, noting that the British Merchant Navy (then the world’s largest) at the start of the war comprised 144,000 men and women, of whom about one quarter were Indian. This provides a total of about 232,500 personnel in the Indian armed forces and merchant marine by late 1939. By the end of the war these numbers had risen to Army 2,065,554, Air Force 29,201 and Navy 30,748 plus a Merchant Service of about 40,000. The total in late 1945 showed an amazing tenfold increase to 2,165,503, mainly men supported by a small number of women in uniform. The Indian Army was then the largest volunteer army in known history.

The Racial Divide

Religious divisions within the subcontinent are ages old and deep-rooted. From earlier times soldiers were predominantly recruited from the more warlike Muslims or Sikhs of north-western India. Additionally there was a sizable number of Ghurkhas from Nepal. Some high caste Hindus, not including Brahmans, were also included. Soldiers from this echelon were generally thought to be immune from an anti-British feeling that was becoming prevalent elsewhere.

But this mine was not bottomless and during the First World War it was necessary to cast the net further into Hindu communities to find the required number of recruits. During the Second World War the situation was exacerbated by phenomenal growth in a short space of time resulting in social transformation in the composition of the armed forces, with many more Hindus coming from southern India. With these increases the ratio of experienced British officers declined. There was also an imbalance, with a tendency to retain the mainly Muslin martial classes in front line regiments, at the expense of others.

India at War

As early as 1937 plans had been made for sending Indian troops to help garrison overseas outposts. Even before the outbreak of the Second World War, India had deployed 10,000 troops to help garrison Egypt, Aden, Singapore, Kenya and Iraq. In September 1941, after allowing for internal defence against an uncertain Russian position on the north-west frontier and a growing Japanese threat in south-east Asia and with a further build up in recruitment, India was able to deploy one division to Malaya and three more divisions to Iraq to protect Anglo-Iranian oilfields. In June 1940, with the fall of France and with Britain in dire need of experienced troops, eight regular British Army regiments were returned home from India and replaced by less experienced territorial regiments. By early 1942 some 264,000 Indian troops were serving overseas, including 91,000 in Iraq, 50,000 in Malaya, 20,000 in the Middle East and 20,000 in Burma.

Into Europe

There is little record of the Indian Expeditionary Force that sailed to France in December 1939. The Force was of brigade strength and mainly comprised men from the Indian Army Service Corps, partly equipped with four companies of mules. These were the first Dominion/Empire troops to come to the aid of the mother country during WWII. Embarkation was completed at Bombay on 10 December aboard the troopship Lancashirealong with four smaller British Indian ships, of which two were fitted with ‘tween deck stalls for mules. The total troop strength was about 4,000 officers and men. The convoy was escorted by the Australian cruiser HMAS Hobarttogether with two AMCs. They reached Marseilles on 26 December and the force was soon disembarked in cold, wintry conditions to entrain for destinations in Northern France.

In an interesting aside, lest we think that it was Indians alone who still relied on four legged transport, their convoy, supported by two further ships, was now made ready to embark the leading (6th) Brigade of the 1st British Cavalry Division, the last of a long line of horsed formations to serve with the British Army. After crossing the Channel from Southampton a total of 9,000 men and 4,000 horses were entrained for Marseilles and final shipment to Haifa in Palestine. Before the fall of France and the virtual closure of the Mediterranean to allied commercial shipping, nearly all troop movements to the Middle and Far East were made via Marseilles, thereby avoiding the considerable Atlantic U-Boat menace.

North and East Africa

The war in North Africa started in September 1940 with the movement of a large number of over-confident Italian troops from the relative safety of their cantonment in Libya towards Egypt. In the western desert they were opposed by General Wavell who had a numerically inferior mixed British and Indian force. The newly arrived Indian 4th Division was poorly equipped, had little training and no experience in desert warfare. However, morale was high, in this the first formation of the Indian Army to serve on the frontline of the war.

Skirmishes between the two sides occurred in late October 1940 but on 7 December Wavell launched his attack. Some 36 hours later the Battle of Sidi Barrani was at an end with 38,000 Italians plus much equipment captured. This was the first major victory by the Allies in WWII. This victory was however bitter-sweet for the Indians, who had performed well, as the 4th Division was replaced by the inexperienced Australian 6th Division, and the Indians moved to the less important theatre in East Africa.

Sudan was initially defended by three British battalions, but as of late September 1940 the Indian 5th Division began arriving. They included the 10th Infantry Brigade commanded by Brigadier William Slim, who had been with the army in India since 1919. In Sudan the going was much tougher with Italian troops occupying well defended positions and with superior air cover. The Allied cause was improved by the insertion of the Indian 4th Division. With considerable hard fighting the East African campaign was over with the surrender of Italian forces in May 1941.

Malaya and Singapore

After first becoming comrades at Gallipoli a quarter of a century earlier Australian, British and Indian armed forces were to meet again in less auspicious circumstances in Malaya in 1942. This battleground has been called the greatest defeat of the British Army when it was routed by a smaller but much better trained Japanese Army, culminating in the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. In numerical terms the Indians were the senior partners with about 50,000 troops, British 33,000, Australian 17,000 and Malays 2,000. Most of these surrendered to an uncertain future.

The Mediterranean

The 6th Australian Division, which had relieved the 4th Indian Division in North Africa, took Bardia on 5 January 1941. Three weeks later Tobruk had fallen and the retreating Italians were pursued along the Libyan coast by exuberant Australians. Over 130,000 Italians were taken prisoner with hundreds of tanks.

This situation could not be allowed to continue and Germany decided to stiffen Italian resistance in North Africa, which in turn would not allow British and other Allied forces to withdraw troops to the European theatre. Ominously, the first of General Rommel’s Afrika Korps landed on 7 February 1941.

In March 1941 the now experienced Australian 6th Division was sent to Greece and replaced by new troops including the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade. Later that month the new boys were badly mauled by a Panzer Division. The Australians retreated to Tobruk. The Indians were isolated at Mechili where they were surrounded and, after suffering 25% casualties, surrendered.

On 11 April German and Italian troops stood at the gates of Tobruk. The 4th Indian Division which had just returned from East Africa was sent to help relieve the garrison. With Rommel’s forces being over-extended his attack was called off and on 4 December Tobruk was saved. The war in North Africa see-sawed before Rommel, with numerically inferior forces and little hope of fresh supplies began his fresh attack. He again reached Tobruk on 20 June 1942 which was defended by British, Australian and Indian troops. The ferocity of the attack surprised the defenders and early the next day the 22,000 strong garrison surrendered. The fall of Tobruk sent shockwaves far beyond North Africa as far as Washington. The retreating 8th Army took up new defensive positions at El Alamein.

In July 1942 rumours were rife of Rommel’s imminent entry into Cairo. Women and children were streaming out of the city in all modes of transport. The Commander-in-Chief, Auchinleck, was with his 8th Army squaring off against Rommel in the desert at El Alamein. This position, well within the Egyptian frontier, had been chosen because of its defensive capabilities with high ridges and salt marshes making it largely impassable to tanks.

The 10th Indian Division garrisoned further west at Matruh had been cut off by the attacking Axis forces. The decision was made to fight their way back to Alamein and this breakout proved successful. However, by the time they reached Alamein they were in a poor state and sent back to the Nile to re-equip.

Other Indian units with no experience of desert warfare were deployed on sectors of the Alamein Line and received a baptism of fire in confronting tanks from the crack Afrika Korps. In the end Alamein became an expensive stalemate but unable to dislodge the Allies, Rommel withdrew and Auchinleck did not pursue the enemy. Auchinleck was relieved of his command and sent to India with Montgomery taking over the Eight Army.

The Burma Road

To many Australians, mentioning the Burma Road takes their thoughts back to a railway built in 1943 covering the 258 miles (415 km) of rugged terrain through Thailand providing support to Japanese forces in the Burma campaign. This was built at great human cost by locals and 60,000 Allied POWs. There is, however, another much longer Burma Road of 717 miles (1,154 km) running through mountainous country linking southern Burma with China and built in 1937-38 by 200,000 Burmese and Chinese labourers. Until cut by the Japanese during WWII this gave vital British and American aid to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Chinese Army, who had been involved in the Sino-Japanese War since July 1937.

The British may have underestimated the capabilities of Chiang’s poorly provisioned but battle-hardened troops, who were willing to support them in Burma. There may have also been an underlying suspicion that increased American aid through Burma to China might unduly influence future political post war affiliations, running counter to those of European colonial interests. As a result the Indian Army fighting against the Japanese in Burma was initially poorly resourced; in 1941 this comprised 22,000 mainly British, Indian and Burmese troops.

Initially Burma did not feature in Japanese plans but as Malaysia had fallen so easily they sensed similar opportunities in Burma. By capturing the country they hoped to seal the western boundary of their planned Co-Prosperity Sphere to replace the older European dominated colonies. The Japanese offensive with 25,000 troops began on 22 January 1942 and the onslaught was ceaseless against ill-prepared defenders. By early April the skies were alight as the Allies set fire to fuel tanks from their precious Burma oil fields. By the end of April 1942 Allied troops together with countless civilians had evacuated Burma.

Following the evacuation of Rangoon, India entered into its darkest days. Japanese forces next occupied Indian territory, seizing the Andaman and Nicobar Islands at the south-eastern entrance to the Bay of Bengal. Now within the range of Japanese aircraft and warships, the eastern Indian seaboard became unsafe for Allied shipping. The Royal Navy’s Far East Fleet, fearful of Japanese air attacks, evacuated Ceylon to new bases in the Maldives and Kenya; this mighty navy had been humbled, it had lost its raison d’être and, for a while, it had lost control of the Indian Ocean.

While the Allied cause did indeed look bleak, this was also the zenith of Japanese conquest, as Japan had overextended its resources and supply lines. Soon after, the superiority of the American industrial expansion and military manpower became evident and, after hard-fought encounters, there was a glimmer of reversals in fortune. It was time to plan for the re-conquest of Burma.

Re-conquest of Burma

The first Arakan offensive began in late 1942 with the 15th Army Corps comprising nine brigades. The offensive was aggressively pursued by the United States, which was providing vast quantities of much needed logistic support, and who considered an attack essential to keep Chinese Nationalist Forces engaged against the enemy in northern Burma. Britain favoured a gradual build-up and more cautious approach but the offensive was approved. The initial landing on the Burmese coast went well as two defending Japanese brigades withdrew to the cover of better defended positions. It was then found impossible to dislodge the Japanese and after nearly two months of battering a Japanese counterattack was launched and, by mid May, the Indian Army was withdrawn having suffered a humiliating defeat.

The Arakan campaign had sent shockwaves throughout the army and had fostered an aura of invincible Japanese fighting skills. A study of lessons learnt came to the ironic conclusion that a central problem with the recent build-up of the Indian Army, and making it suitable to mechanised warfare in North Africa, was that it had forgotten basic skills necessary in the jungle-clad mountainous Burmese terrain. It was back to the basics of 1915 Gallipoli with the reintroduction of the Mule Corps, and even bullocks and elephants were called into service in transporting heavier loads. Overall training was much improved with emphasis on morale, health and discipline to enhance fighting skills. New tactics were developed and employed to counter enemy dispositions.

At the higher level the C-in-C of the Indian Army, Auchinleck, was largely bypassed with Mountbatten, who had distanced himself in Colombo, as the new overall South East Area Commander (SEAC). The Eastern Command was renamed the 14th Army and placed under the command of General Slim.

On 30 November 1943 the Army was ready to undertake a new major offensive in Burma. While costly frontal attacks could not always be avoided, new tactics of infiltration and encirclement (learnt from the Japanese) often worked and compelled the Japanese to retreat. This, together with massive air superiority, gradually wore down Japanese resistance and the once invincible troops were finally repelled at great cost to both sides. Bitter fighting continued for many months. The monsoon made effective fighting impossible for about half of the year, but a lack of supplies and fresh troops took its toll upon the Japanese resulting in their eventual collapse after many thousands of deaths and casualties, with a final retreat into Thailand in August 1945.

Civil Disobedience and the Quit India Campaign

Early reversals of fortune of British and Allied forces fighting in Europe and North Africa gave impetus to the Congress-inspired Indian Independence Movement. This was exacerbated by Japanese air raids on the subcontinent which started on Calcutta on 19 December 1941.

On 9 August 1942 the leadership of Congress was arrested and placed in custody. This triggered a popular uprising, the most serious since the Great Mutiny of 1857. A ‘Quit India Movement’ became a catchcry under which public property, with government buildings including police stations, post offices, railways and telegraph installations were damaged and destroyed. The Indian Army stood firm to maintain law and order and where necessary opened fire upon its own citizens. On 10 February 1942 Gandhi started a hunger strike in support of the independence movement; this could have had dire consequences should he have died a martyr. Fortunately, on 2 March he ended his fast, regained his health, and gradually order was restored.

The Indian National Army

Associated with the independence movement was the Indian National Army (INA) and its leader Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose was born to a wealthy legal family and educated in India but later attended Cambridge. He was a radical leading member of the Indian National Congress, rising to become president in 1938. In the mid 1930s he had visited both Italy and Germany where he was feted for his anti-imperialist views. Here he met a young Austrian woman, Emile Schenkl, and they later married.

After differences with Gandhi and other Congress leaders Bose was ousted from the leadership in 1939 and considered a subversive. He was subsequently placed under house arrest. However he escaped from India and in 1941 arrived in Germany where he established a ‘Free India Radio’ and helped form a 3,000 strong ‘Free India Legion’ from disaffected POWs who had been captured in North Africa. While of significant propaganda value the ‘Legion’ never saw action and was mainly used in policing roles in the Netherlands and the Low Countries.

In view of Japanese successes in south-east Asia, Bose’s talents were considered more important in this theatre. At Kiel on 9 February 1943 he boarded the German submarine U-180 which took him to Madagascar where he transferred to the Japanese submarine I-29 from which he disembarked in Sumatra in May 1943. Bose was then flown to Tokyo for high level discussions on how the 60,000 Indian civilians and POWs in Singapore might be recruited into the INA.

A mass gathering of Indians in Singapore was transfixed by the oratory and charisma of this amazing individual – one of his quotes is: Give me your blood and I will give you freedom. Over 20,000, including many officers, joined the INA and Bose was even able to recruit a volunteer female regiment to provide nursing and welfare support. Recruits may also have been encouraged by the alternative offered, of joining labour camps in New Guinea with a very uncertain future.

The INA were employed taking control of the Indian, but Japanese occupied, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the then British, but Japanese-occupied Christmas Island (post-war this became an Australian Territory). INA also provided guards overseeing Allied POWs at Changi prison. Their greatest assistance to the Japanese war effort was in providing troops to assist in the defence of Burma. Bose had the vision of being the great liberator, leading his army from Burma into India, with the population flocking to his banner. While this was never to eventuate there would have been immense unrest if it had succeeded. With the end of the war in sight Bose was moved to Formosa where this misguided patriot died following an air crash in August 1945. He was 48 years of age.

British authorities were determined to make an example of the INA officers and soldiers as traitors. However, the days of the Raj were over and the authorities were out of touch with the common man. Senior officers were deeply shocked and dismayed by the attitude of the majority of Indian troops who had remained loyal; they were now willing to regard members of the INA as independence fighters, whom many believed were true patriots. After a few showpiece trials the majority of prisoners were released to be welcomed back into the community as heroes.

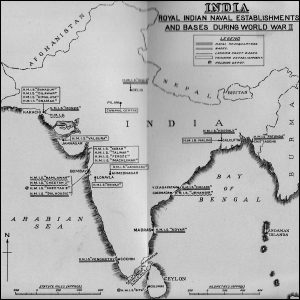

The Royal Indian Navy

Not unlike the RAN, the Royal Indian Navy traces its history back to colonial times, in fact a long way back, to the East India Company which was established in 1599 and formed a fleet of fighting ships in 1612. Subsequently there were various changes in title until the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) was formally proclaimed on 2 October 1934.

Under the overall protection of the Royal Navy the Royal Indian Navy was often overlooked and at the start of the Second World War the RIN had only eight warships. However its wartime growth was considerable, which included the establishment of a Women’s Royal Indian Naval Service.

RAN ships were frequently attached to the Eastern Fleet and worked with RIN counterparts. One of the more tangible contributions was the transfer of four Australian built corvettes, the rather grandly named, HMI Ships Bengal, Bombay, Madras and Punjab which were all commissioned in Australia in 1942. when Bengal was escorting the armed Dutch tanker Ondina off the Cocos Islands In October 1942 she was attacked by two Japanese commerce raiders armed with 6-inch guns. Bengal and Ondina sank one raider and the other beat a retreat. Two other corvettes, HMA Ships Ipswich and Launceston combined with HMIS Jumma in sinking the Japanese submarine RO-110 in the Bay of Bengal.

Post War – the Navy goes on Strike with the end of an Empire

The year 1946 was one of turmoil. Inflamed by the INA trials there were uprisings, demonstrations and strikes. The loyalty of the armed forces was also tested when on 18 February 1946 the Royal Indian Navy mutinied. This started in Bombay where dissatisfied sailors deserted their ships and marched through the city holding aloft portraits of Subhas Bose. A major point of protest was alleged discrimination against Indians by British officers. The mutiny spread throughout the country affecting 78 ships and 20 establishments with over 20,000 ratings involved. There was also sympathy from their Army and Air Force colleagues and substantial public support.

The leaders of Congress demonstrated tangible political maturity and negotiated a settlement with the mutineers to return to their duties and, in return, they would ensure that their grievances were addressed. As quickly as it started the mutiny was over.

The mutiny demonstrated to the British that they no longer had control of the Indian armed forces and political power was with the Indian people. Following elections on 2 September 1946 Nehru became vice-president of the viceroy’s Executive Council and thus effectively prime minister. A new British administration under Labour leader Attlee recalled Governor-General Wavell and appointed Mountbatten as his successor – but not for long, as Attlee also announced that Great Britain would withdraw from India by June 1948. The Raj was over and the Empire no more.

Summary

India, a nation with a tumultuous upbringing, has long sought peaceful independence. The Australian–Indian relationship, however, was not brought about by peaceful means but forged out of marching and countermarching to imperial tunes, which lasted until the demise of an outmoded empire.

We now seek inspiration for a final chapter in this series addressing the maturing relationship between our two countries from the time of Independence to the present day, which also looks into mutual issues affecting regional defence in the Indian Ocean. This might also acknowledge a different Australia, one with rapidly changing demographics, with a decided cultural shift towards Asia.