The following address was delivered Captain Christopher Skinner RAN Rtd during the 75th anniversary ceremony conducted by HMAS Kuttabul on Garden Island, Sydney 1 June 2017.

Good morning to you all and welcome to this service to commemorate the loss of the first HMAS Kuttabul and the 27 sailors who died that night 75 years ago when the Japanese Navy attacked allied forces in Sydney Harbour.

I am honoured to be here today on behalf of the Commanding Officer of HMAS Kuttabul, and also to represent the Submarine Institute of Australia.

I would like to acknowledge material and inspiration from the address delivered last year by Captain Paul Martin RAN (retired); also from the book entitled ‘A Very Rude Awakening.’ by Peter Grose published by Allen & Unwin in 2007, and from Wikipedia entries.

The attack on Sydney Harbour by three midget submarines was the opening salvo in a Japanese submarine campaign off the east coast of Australia that ultimately sank 21 ships, attacked a further 19 vessels and claimed the lives of 670 men and women. In Australia, this campaign is little known, yet more lives were lost along this stretch of coast than on the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea.

In this service today we remember and commemorate all the servicemen who died in the Battle for Sydney Harbour on the night and morning of 1st June 1942, 75 years ago. The names of the 21 allied sailors and of the six Japanese submariners will be recited later in this service, as we honour their courage and sacrifice in the service of their respective countries.

The midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour was but a part of a wider naval strategy by Admiral Yamamoto. Attacks occurred on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 with limited success, and then in Sydney Harbour and Diego Suarez, Madagascar in May/June 1942.

The submarine capability to make these attacks was at the cutting edge of submarine technology of the day. The Type A Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines of 47 tonnes submerged displacement, 24m in length, 1.8m beam and a crew of two, were armed with two muzzle-loaded torpedoes plus a scuttling charge.

Each of the three midget attack boats was carried on the after casing of a 3700 tonne fleet submarine. Experience from the unsuccessful Pearl Harbor attack was applied to provide access to the midgets via a watertight hatch from the mother boat plus attachment releases operated from within the submarine.

The midgets were capable of submerged speeds to 19 knots for a range of 18 nautical miles or at low speed up to 100 miles. Test depth was 30 meters. They were single mission boats, but the specially-trained crews were to be recovered for further actions

Two other accompanying fleet submarines carried reconnaissance seaplanes in sealed deck containers. These were the revolutionary E14Y Glen aircraft and were designed for rapid preparation and launch and recovery on the open ocean.

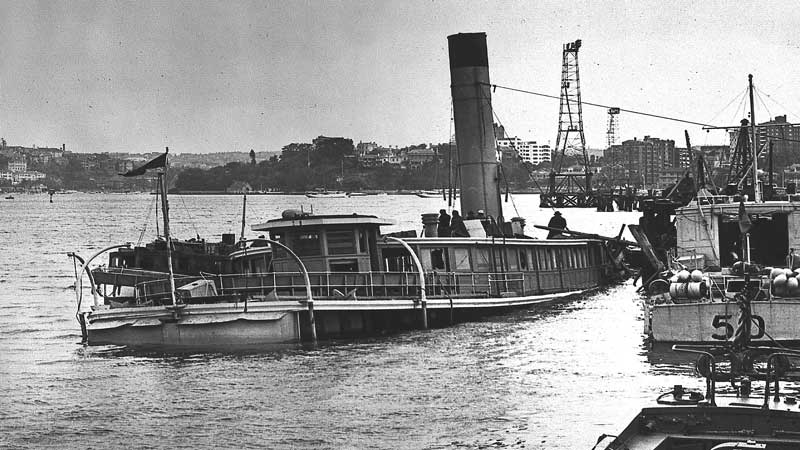

The ferry Kuttabul had been built in Newcastle NSW and started life as a steam powered ferry in 1922 as one of the largest ferries ever to operate on the inner harbor routes. She was certified to carry over 2000 passengers. However, with the opening of the new Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 Kuttabul became redundant and she was laid up.

After the outbreak of WWII, and with war looming in the Pacific, the Navy requisitioned and commissioned Kuttabul in February 1941 for use as a depot ship. She provided accommodation for up to 150 allied naval personnel awaiting transfer to ships and was berthed here at Garden Island only meters from where we are gathered today.

After Pearl Harbor Japanese submarine strategy was directed to two areas – westerly in the Indian Ocean and easterly to the south west Pacific focused on Suva, Sydney and Auckland. The eastern direction was reconnoitered with submarine-carried Glen aircraft over Sydney in February of 1942 and then again on the day prior to the attacks on 1st June.

On that night, the three midget submarines M27, M22 and M24 entered Sydney Harbour with the intention of attacking Allied warships. Over 30 warships were in the harbor including HMA ships Canberra, Adelaide, Kanimbla and Westralia. There were also a number of Allied warships including the Dutch submarine K9 and the American cruiser USS Chicago. A number of the ships in port had recently returned from the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May 1942.

One reconnaissance aircraft took off in the early hours before dawn on 29 May. The aircraft made several passes over Sydney Harbour enabling the pilot and his observer to sketch the position of the anti-submarine defences and the position of some of the warships. The seaplane was both seen and heard but no one suspected the presence of a Japanese Force so close to Australia’s largest city.

Following the success of the reconnaissance flight the Japanese submarine commander decided to launch the attack. Shortly after entering the harbour, midget M27 was spotted caught in an anti-submarine net. Realising they were trapped the crew destroyed their vessel with the installed scuttling charge. Neither man survived. The noise of the explosion hurled debris into the air and heralded the beginning of a wild night of action on Sydney Harbour.

M22 was spotted near Taylor’s Bay and was attacked with depth charges by Naval auxiliary patrol craft. With their vessel damaged, and realizing they would not be able to complete their mission or return to the parent submarine, the crew took their own lives.

At about 0030 on the morning of 1 June, a third boat M24 which had earlier avoided fire from USS Chicago and HMAS Whyalla gun crews, manoeuvred to take up a firing position. She aimed at Chicago, which was moored to a buoy to the east of Garden Island, and fired her two torpedoes.

The first torpedo passed astern of the Chicago, went under the Dutch submarine K9 which was berthed outboard of Kuttabul, and exploded against the seawall next to Kuttabul. The resulting explosion and shockwave severely damaged the K9 and lifted Kuttabul up and then slammed her down again and she began to sink.

The second torpedo finished up at the seawall nearby without exploding and was not discovered until later in the morning causing some alarm.

This daring and spectacular submarine action had an extraordinary impact on the national and strategic thinking of the day, precisely as it was intended to do.

In two months’ time the RAN will commemorate the commissioning of submarine base HMAS Platypus across the harbour in 1967, twenty five years after the Japanese submarine attack on Sydney. In the period since then, Australia has rediscovered the disproportionate maritime effects of submarine capability, as has been articulated so very well in the 2016 Defence White Paper and its predecessors.

Today with UAV reconnaissance and autonomous and remotely operated armed vehicles, Australia’s submarine force is enabled to conduct the same kind of action on a would-be attacker on Australia’s national interests. This capability provides Australia’s primary strategic deterrent.

Recalling the attack on Sydney we must pay tribute to all the men who lost their lives that night in the service to their country, the 21 Australian and British sailors and the six Japanese sailors.

The words of RADM Muirhead-Gould, the Naval Officer in Command of Sydney Harbour at the time, are worth repeating:

“It must take courage of the very highest order to go out in a thing like a steel coffin. Theirs was a courage that is not the property of any one nation; it is the courage shared by the brave men of our own countries as well as of the enemy. These men were patriots of the highest order.”

When the bodies of the four Japanese crew members of M22 and M27 were recovered it was decided that they be given the honourable burial which Australia would expect for her own dead in similar circumstances. The four Japanese submariners were accorded full military honours at Rookwood Cemetery, Sydney on 9 June 1942. Following cremation their ashes were returned to Japan later that year when Japan’s Ambassador to Australia was repatriated.

The M24, which had managed to fire her two torpedoes, submerged and disappeared that morning in 1942. She stayed missing for another 64 years until 12 November 2006 when a group of recreational divers discovered the M24 in 56 meters of water off Sydney’s northern beaches. There she rests as a war grave. The Sydney Morning Herald today reports on the archaeological survey in progress to model the site without disturbing the wreck.

In closing, today we remember the audacious submarine attack, and learn many lessons for today as we commemorate the bravery and sacrifices of the sailors who lost their lives when World War II came to Sydney Harbour.

LEST WE FORGET.