- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Battles and operations, History - general, WWII operations, WWI operations, Royal Navy

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Shropshire, HMAS Australia I, HMAS Sydney I

- Publication

- December 2018 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

The name Scapa Flow was synonymous with naval operations in both world wars as a safe anchorage for vast fleets seeking to control access to the seaborne approaches to northern Europe. So where and what is Scapa Flow, how safe was it and, what does it have to do with Australian naval history?

The Orkney Islands lie some 10 miles (16 km) across the notorious Pentland Firth off the northeast tip of the Scottish mainland, a turbulent stretch of water where the fury of the North Atlantic meets the outpouring of the North Sea. They comprise 70 windswept but surprisingly fertile islands1of which 20 are inhabited by 23,000 hardy folk of Norse ancestry. A further 80 km north lie the slightly larger and more remote Shetland Islands. These two island groups were but stepping stones to the Vikings who, more than a thousand years past and using their powerful longships, came from Scandinavia and created a vast empire which covered all of Scotland and Ireland and much of northern England. They then went further west to the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland and reached North America more than four centuries before Christopher Columbus.

After the Norman (French) invasion of England in 1066 the Viking influence was subdued with both England and Scotland becoming independent kingdoms. However, the Orkney and Shetland islands remained under Norse control until 1468 when they were ceded to Scotland as a dowry upon the marriage of Princess Margaret of Denmark to James III of Scotland.

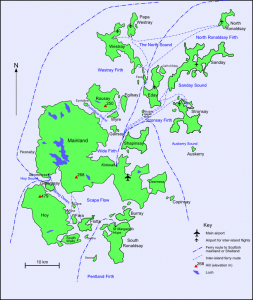

The Vikings called Scapa Flow Skalpafloi and it is one of the world’s largest natural harbours of about 312square kilometres, six times larger than Sydney Harbour. In its original state there were 17 passages to the sea through the chain of surrounding islands, providing good access to open water, but these were difficult to defend. The anchorage was of firm sand at a depth of between 30 and 40 metres.

Early History of the Flow

While the existence of the Flow was known to many seafarers it perhaps first came of interest to Antipodeans following the explorations of Captain Cook, specifically Cook’s third and final voyage, in which he was killed and his second in command, Lieutenant Charles Clerke, died through illness. After four years absence from their homeland, command of the expedition passed to the remaining senior officers, Lieutenant John Gore (Resolution)and Lieutenant James King (Discovery).After so many perils what could be easier for these experienced navigators than passage over the final leg from Cape Town to London in the northern summer?

They opened the English Channel in early August 1780 but were beaten back by strong easterly gales and tried in vain to find shelter on the west coast of Ireland. Neither their long lost leader Cook, who prided himself on the exactness of his navigation, nor their Lordships of the Admiralty would have been impressed when they eventually anchored off Stromness in the Orkneys, over five hundred miles (850 km) from their intended destination.

At Stromness they took on provisions and waited a month for favourable winds. Lieutenant King was sent overland to acquaint the Admiralty with the results of the expedition. One crew member died and another found time to marry a local lass. It was not until 4 October that the ships finally made the Thames and a subdued welcome.

While a prominent fishing industry developed around these islands there was little commercial interest other than by the Hudson Bay Company who used the Orkneys as a recruiting base for ships engaged in the lucrative Canadian fur trade.

Twentieth Century Development

In the early 1900s, with growing rivalry between Britain and Germany, the need for a Royal Naval fleet base covering the approaches to the North Sea and the North Atlantic was identified. After a series of fleet exercises around the northern approaches, Admirals Fisher and Jellicoe enthusiastically pursued the need for a fleet base to be developed at Scapa Flow. Work began in 1912, firstly near the main town of Kirkwall, but in October 1914 the base was moved further south to Lyness.

The Royal Navy was also conscious of the potential threat to its bases posed by sea mines. Accordingly, in 1910 the Royal Naval Reserve Trawler Section was formed to provide a nucleus of vessels and crews for minesweeping duties. As the war progressed about 1,500 fishing trawlers and a similar number of smaller drifters were brought into naval service. Of these 250 were lost, mainly to enemy mines. The tough men who manned these ships did not wear uniform and remained under control of their skippers. A skipper’s formal dress was a bowler hat and tweed jacket, which in tribute to their new role was often adorned with Navy-issue brass buttons.

With most of the navy relying on coal, as soon as ships arrived at Scapa coaling ship was undertaken, a process that continued day and night without stop until completed many hours later. With the potential submarine threat colliers were also used to screen the capital ships making them less vulnerable to attack.

Wooden wharves and a slipway for smaller vessels were constructed at Lyness on the island of Hoy in 1916 and a naval base grew, with stocks of coal and oil, stores and administrative support. A cemetery was dedicated as a resting place for those who lost their lives in these waters, which eventually included 18 German sailors and six Australians.

Boom defence measures were put in place, manned by a number of drifters which also supported the warships when in harbour. Block ships were sunk to restrict access to the numerous channels and one of the first of these was SS Aorangi. In mid-1914 Aorangi had been chartered by the RAN from the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand as a supply vessel which accompanied the Australian fleet when capturing German New Guinea. She was then sold to the Admiralty who took her to Devonport for refit, but being found beyond economic repair she was taken to Scapa Flow and scuttled as a block ship in August 1915.

After the capture of German New Guinea and the chase for von Spee across the Pacific, HMAS Australia joined the pride of the fleet, the fast and powerful battlecruiser squadron, on 17 February 1915. While they were part of the Grand Fleet which was based at Scapa Flow, the battlecruisers were held further south at Rosyth, a naval dockyard across the Forth from Edinburgh. Rear Admiral Sir David Beatty flew his flag in HMS Lion, other ships of the squadron were Australia and HM Ships Indefatigable, Indomitable, Invincible, Princess Royal, Queen Mary and New Zealand.

The main concerns were not German capital ships, which they were keen to engage, but the unknowns of mines and submarines and also Zeppelins, which acted as lookouts and could drop not very accurate bombs from height, beyond the range of anti-aircraft fire. As a defence against submarine attacks the squadron usually entered and left harbour after dark at high speed and with dimmed navigational lights. Patrols and exercises with the squadron and the Grand Fleet resulted in Australiamaking frequent calls to the Flow and being anchored there for days at a time. The lack of facilities at the Flow meant that this was a dreary and monotonous location when compared to Rosyth with the not far distant beckoning lights of Edinburgh.

On 22 April 1916 the Fleet was in the North Sea searching for suspected enemy ships and proceeding in thick weather on a zig-zag course at 20 knots. At about 15.45 Australiarammed New Zealand,not once but twice, suffered extensive damage to her stem and was holed on her starboard side. While New Zealandescaped with slight damage which was repaired locally, Australiamade the sad and slow journey back to Rosyth. Here it was ascertained she needed docking and was sent to Devonport for repairs. By the time she reappeared at the Flow, most of the capital ships were at Jutland. It is noteworthy that her near-sisters Indefatigable,Invincibleand Queen Maryexploded and sank at Jutland with huge losses of life2.

In August 1916 the light cruisers HMA Ships Melbourneand Sydneywere transferred to the Grand Fleet and in October joined the Second Light Cruiser Squadron, also based at Rosyth but they too spent considerable time in the Flow.

Unfortunately, there is a series of naval tragedies associated with Scapa Flow. Immediately after Jutland the cruiser HMSHampshirewas sent to the Flow to embark Field Marshall Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War and his staff and take them on a secret mission to meet the Czar, with the aim of securing greater Russian support to the war effort. On 05 June 1916 Hampshire,with two escorting destroyers, sailed into strong winds and made for the western side of Orkney to provide better shelter for her escorts. As the gale increased the escorts, who could not maintain station, were dismissed, and the cruiser continued alone. That evening when about two miles off the coast she struck a mine that had been laid days earlier by U-475. She quickly sank and of her 735 crew and 14 passengers only 12 crew survived; Lord Kitchener’s body was not recovered.

Australians were involved in the loss of the battleship HMS Vanguard which suffered a massive internal explosion on the night of 9 July 1917 caused, it is believed, by incorrectly stowing faulty cordite charges. Sydney was the nearest ship and her boats were first on the scene when they rescued the only two men to survive. Unfortunately, two of Sydney’s own crew were on board the battleship in cells and they both died. Like most of the 843 men who were lost in this disaster they have ‘no known grave but the sea’.

Owing to the lack of entertainment the Admiralty requisitioned two merchantmen, SS Gourko and SS Borodino, which were stationed at the Flow, their mission being to bring cheer to the fleet and act as floating canteens, amenities and entertainment centres. On the night of 9 July 1917 a number of Vanguard’s officers had been invited to a concert party being hosted by Gourko.Amongst those attending were the ship’s Gunnery Officer Commander Wilfred Custance and Midshipman Reginald Nichols who had recently joined Vanguard. As these officers were not aboard Vanguard at the time of the explosion they were not listed amongst the survivors, which is of later interest to the history of the RAN3,4.

Fate of the German Fleet

One of the conditions of the Armistice included the surrender of the German Navy, requiring the fleet to disarm and proceed to Britain for internment, with steaming crews only. The melancholy surrender of the German High Seas Fleet began on 20 November 2018 when 150 submarines began arriving at Harwich. This was followed the next day by 74 surface ships of the once mighty fleet which, with an RN cruiser HMS Cardiff in the van, steamed into the Firth of Forth through the Allied Fleets arranged in two columns.

Britain was determined to put on as spectacular a display of its superiority as possible. Apart from the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, there were detachments from other stations, an American Battle Squadron and a French Flotilla, in total comprising 240 ships. After anchoring in the Forth arrangements were made for the German ships to proceed in small flotillas to Scapa Flow. Reminiscent of the Sydney/Emden battle of 1914, and now with replacement players with similar names, in one of their final wartime acts Sydney escorted the captured German cruiser Emden into a safe anchorage in the Flow.

Fearing that his ships were to be humiliatingly divided up between the victorious Allies, their Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ludwig von Reuter devised a plan of frustration. On Sunday 21 June 1919, with good weather prevailing, the guarding ships of Vice Admiral Fremantle’s 1st Battle Squadron was taken to sea for exercises. Temporarily free of his guards, von Reuter gave a pre-arranged signal that resulted in 52 of his 74 ships being scuttled by their crews under the unsuspecting noses of their captors.

Second World War

With war clouds looming in 1937, work began on once more making the Flow available as a major fleet base. Large underground fuel storage tanks were constructed plus torpedo and ammunition depots. This was also the beginning of more sustainable personnel facilities for accommodation and recreation such as a hospital, cinema, theatre, several churches and a NAAFI5. By 1940 over 12,000 military and civilian personnel were stationed here and they were later joined by much needed female company with up to 1,500 WRNS arriving at the new base now known as HMS Proserpine.

Before the outbreak of war Britain negotiated with Norway for the lease of much needed merchant ships from its fleet, which included a large number of tankers. While Norway was neutral an agreement was reached. On 9 April 1940, possibly to the surprise of the Allies, Germany carried out a seaborne invasion of Norway. By the time the Home Fleet at Scapa was in a position to respond Germany had control of the Norwegian seaboard and air space. The Norwegian campaign was over within a matter of weeks.

When Russia entered the war on the Allied side in mid-1941 the most direct route for providing them with essential supplies was around the north of Norway to Murmansk and Archangel. In winter months with only a few hours of daylight, physical elements of snow and ice were the greatest danger but in the summer with almost perpetual daylight it became a suicide run. Convoys were constantly shadowed by reconnaissance planes and then attacked around the clock by enemy aircraft, submarines and surface vessels. The Home Fleet based at Scapa had the responsibility for protecting these convoys. The losses of ships, equipment and men from these convoys in 1942 was sickening, but gradually from the next year, improvements were made in the Allies favour with telling blows being made on the enemy forces.

From the outbreak of war ships of the RAN integrated with the RN in aid of the mother country. After work-up at Scapa Flow the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia patrolled with the Home Fleet in Atlantic and Arctic waters. She later sailed for north-west Africa to help neutralise the French naval base at Dakar and then refitted at Liverpool before returning home to the Pacific in 1941.

Just after a month following the declaration of war the German Navy gained a significant moral victory over the Royal Navy when one of its submarines U-47,vskilfully navigated by her captain Gunther Prien, penetrated the defences of Scapa Flow. Here she found the old dreadnought HMS Royal Oakvat anchor.

We have already met Reginald Nichols, the midshipman who had an extremely lucky escape attending a concert party when his ship Vanguard exploded and sank at the Flow in 1917. Now twenty-two years later Commander Nichols is Executive Officer of Royal Oak and asleep in his cabin when awoken a little after 1.00 am by an explosion near the bow of his ship. An initial investigation assumed the cause to be an explosion in the Inflammable Store near the Cable Locker, but thirteen minutes later came three more sickening thuds on the starboard side, all lights wen out and the ship took a severe list. There was now no doubt that they had been torpedoed. With no power it was impossible to lower the larger boats and because of the increasing list not many of the smaller boats could be lowered. Just eight minutes after the last torpedo struck Royal Oakcapsized and sank.

She took most of her ship’s company with her and 833 men perished, many no-more than boys straight out of training. However, over 370 were saved from the water by the drifter Daisy II and the seaplane carrier HMS Pegasus. Amongst those found clinging to a life raft was Commander Nichols. Another to be saved from the icy water was an exchange officer, LCDR Frederick Cook, RAN6.

Also at the Flow was another elderly battlewagon Iron Duke, which had been flagship of the Grand Fleet in WWI. Only days after the Royal Oakdisaster, on 17 October 1939, while serving as depot and harbour defence ship, Iron Duke was badly damaged by Luftwaffe Ju 88 dive bombers and run aground to avoid sinking. She was again attacked by enemy bombers and suffered further damage. As a result of these two disasters the Fleet was temporarily removed from the Flow until defences were improved.

The propaganda value was of immense value to the enemy and Prien became a national hero. These setbacks resulted in an early visit from Prime Minister Winston Churchill who demanded a number of rapid improvements to the defences known as ‘Churchill Barriers’ where causeways were constructed between islands to further restrict the number of entry points into the Flow. These ‘Barriers’ were largely built by 1,200 Italian prisoners of war. Their legacy is remembered in a wonderful chapel built from Nissen huts and scrounged bits and pieces. Improved fortifications with anti-aircraft batteries were also installed around the perimeter of the anchorage. The barriers and the chapel still stand and are important tourist destinations.

The N-class Destroyers

At the commencement of WWII the RAN was gifted five N-class destroyers which were then building in British yards. The history of these ships, HMA Ships Napier, Nepal, Nestor, Nizama nd Norman, all followed a similar pattern. After trials and workups, all proceeded to Scapa Flow where they joined the Home Fleet for duties involving escorting convoys across the North Atlantic. But within months these ships were diverted to the Mediterranean or Eastern Fleets. They all worked hard and had an eventful war but Nestorwas lost after being badly damaged by enemy aircraft near Crete in June 1942.

Napiercommissioned at Clydebank on 28 November 1940 and with barely enough time for workup, her first important task on 15 January 1941, was to transport Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Mrs Churchill from Thurso (Scrabster) to the new battleship HMS King George Vanchored at Scapa Flow. Here they farewelled Lord Halifax on his departure in that ship for the vital position of Ambassador to the still neutral United States.

Three of these ships were to spend more time in northern waters. Nestor sailed with three other destroyers to 72 degrees north to intercept a German weather ship and return with invaluable code books which went to Bletchley Park7.Nepal was part of a dummy convoy sent north to act as a diversion to enemy forces, drawing them away from the real convoy taking essential supplies to the Russian front. Finally, when the intended RN ship suffered engine failure the brand new and fast RAN destroyer Norman proceeded to Iceland to embark Sir Walter Citrine8and a Trade Union Delegation (shades of Lord Kitchener) and successfully took them to, and brought them back, from Russia.

The last RAN ship to have any involvement at Scapa Flow is thought to have been HMAS Shropshire. Following the loss of HMAS Canberra in the Battle of Savo Island the British Government approved the transfer of HMS Shropshire as a replacement. The cruiser was refitted at Chatham under the command of Commander David Harries, RAN, who supervised the refit, her change of crew and transfer to the RAN. Following his arrival Captain John Collins, CB, RAN, assumed command and commissioned her as HMAS Shropshire on 20 April 1943. The new Australian warship departed for Scapa Flow on 1 July for workup and left the Flow on 13 August, arriving at Fremantle on 24 September 1943.

By 1944 the fortunes of war were beginning to turn in favour of the Allies and as the focus of attention shifted from the North Atlantic the importance of Scapa Flow began to decline, with ships moving further south. Shortly after the war’s end the base was placed in care and maintenance and it finally closed in 1957. Afterwards the majority of the buildings were demolished or sold at auction. However, there is sufficient left behind to remind discerning visitors of important war-time operations, especially to the small but impressive Scapa Flow Visitor Centre and Museum which is housed in one of the former oil-pumping stations of the Lyness Naval Base.

Scapa Flow was home to the Grand Fleet in the First World War and the Home Fleet in the Second. In between it became the final resting place of the German high seas Fleet. To this generation it is just a name in history. However, this bleak and mysterious place is something legends are made of and possibly records more recent naval history than any other place on our globe.

Post-War Developments

The post-war prosperity of the Orkneys was much improved with the discovery of North Sea oil, resulting in oil and gas terminals being established at Scapa Flow, and maintenance facilities for this important industry operating from these islands. Of later year’s tourism has also become important and great ships once again ply these waters as part of a growing cruise industry.

Notes:

1 Orcadians have a quaint definition of what constitutes an island. A parcel of land which is isolated by water must be large enough to grow sufficient grass to keep one sheep for one year, anything less than this is a skerry.

2 The battlecruisers Indefatigable, Invincible andQueen Mary were all casualties at the Battle of Jutland. Significant design faults were demonstrated when these ships exploded after enemy projectiles penetrated their decks and entered their magazines with disastrous losses of life and only a handful of survivors.

3 On 22 April 1938 Wilfred Custance was appointed Rear Admiral Commanding HM Australian Squadron. Due to ill health this popular officer was obliged to relinquish his command on the eve of the outbreak of WWII. Invalided home in the transport SS Orontes, taking Australian air crew for training in England, he died at sea and was buried off Aden.

4 Commander Reginald Nichols, RN, was lent to the RAN in 1940 as Director of Plans and later as a captain as Deputy Chief of Naval Staff and finally as Commanding Officer HMAS Cerberus.His older brother Charles Godfrey Nichols, DSO, MVO, RN, was a highly regarded captain of HMAS Shropshire.

5 NAAFI – Navy, Army & Air Force Institutes providing canteen and recreational establishments for Service personnel.

6 LCDR Frederick Cook served on exchange with the RN until 1942 when he returned home to establish the commando training base at Port Stephens (HMAS Assault) and later as Captain F Cook, DSC, RAN he received several commands during an outstanding career.