- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Kate Reid-Smith

In February 1912, a group of ex-Royal Navy (RN) men arrived in the northern West Australian town of Broome. They had left Britain on 23 December 1911 to much British public fanfare, celebrating that these particular English Jack Tars were reclaiming Australia’s pearling industry from the Japanese. They were also spearheading what the Australian Federal government had coined the ‘white experiment’ – a European-only group of diving and diving tending personnel, known collectively as the ‘White Divers’. It was an ambitious White Australia Policy plan, and one aimed at proving beyond doubt that European divers were every bit as good as their numerically superior Asian counterparts.

White Pearls, White Shells, White Nationalism

The White Australia Policy came into law on 23 December 1901. It was legislation based on racial differences, and aimed at limiting non-European immigration to Australia. The main targets were Asians and Pacific Islanders, which was to prove problematic for Australia’s lucrative pearling (not to mention sugarcane) industries, because the majority of pearl diving crews were Asian. That was because from the late nineteenth century onwards, the highly profitable commodity of pearl shell had been the key industry stretching from Torres Strait across to north Western Australia.

At that time, Australia supplied the world demand for highly fashionable pearl shell, and Broome became the pearling capital of the world. The dark side however, was that it was a European-only dominated industry, built first upon exploited Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander labour, and later, Asian migrant workers.

The shift from local to imported Asian labour had been a direct result of depleted shallow water pearl shell resources over time. Inshore scarcity meant deeper water diving was necessary to exploit offshore shell beds. Deepwater diving was not a locally available skillset, but was one readily obtainable regionally. In many neighbouring Asian cultures including Malaysia, Timor Island, the Philippines and Japan, shell diving had long been an important part of daily subsistence and trade relations. It was no accident these nationalities would go on to become the preferred divers recruited into Australia’s pearl shell industry.

Australian pearling was an unregulated industry. Anybody could dive for pearls or pearl shell, anywhere within Australian waters. There were no Australian maritime policing capabilities, nor were there any national or international maritime jurisdictions determining otherwise. As increasing Japanese pearling interests threatened Australian shell resources, and began limiting Australian territorial pearling industry profitability, the Federal Government’s response was swift. One unilateral decision was that from 1912 onwards, there was to be no more active recruitment of Asian pearl diving and dive tender workers, and by New Year’s Day 1913, all non-European pearling employment was to cease altogether.

Walking on Water Fathoms Deep

The decision sent shockwaves throughout the industry. Frantic protest telegrams from pearlers everywhere reached the Prime Minister’s office. The Department of External Affairs was approached for a ‘please explain’ about pre-existing indentured labour contracts. Western Australian politicians fretted at the prospect of losing pearling-driven taxes. Questions of industry sustainability escalated, especially over the scarcity of suitably experienced European divers. Anonymous letters to newspapers earnestly pointed out the financial impacts of ‘whites only’ employment policies, insomuch as wages would be higher, which meant diminished profit margins for everyone. None of which appeared to shift the myopic government focus, that Australian industry should be worked by and for Australian (white) people only.

The other sticking point was that Broome’s multicultural workforce was making a mockery of the White Australia Policy. In Broome, Asian and Aboriginal populations substantially outnumbered Europeans, with the ratio between Japanese and Australian in the unregulated pearling industry being at least two to one. An ethnic imbalance was highlighted by escalating civil disobedience, most notably within Japanese diving communities. From June 1912 onwards for example, mounting convictions emanated from Japanese workers disobeying the direct commands of their European pearling skippers. In one instance, a Japanese crewman even hoisted the Japanese flag on a British ship.

What made matters worse was that Australia’s pearling industry seemed to be an ongoing free-for-all competition. The government had already lost control of large swathes of shell beds to the Japanese, including around Thursday Island. As well, multi-ethnic rivalries and armed clashes over accessing healthy shell beds were starting to range from New Guinea all the way down to Port Hedland. Something had to be done, and that included addressing Broome’s de facto reputation as the epicentre of Australia’s maritime frontier-style wild west. In response to government demands, Broome’s pearlingindustry masters recruited twelve British ex-Navy diving crews. The hope was that this would maintain sustainable industry viability in the impending depletion of Asian workforces.

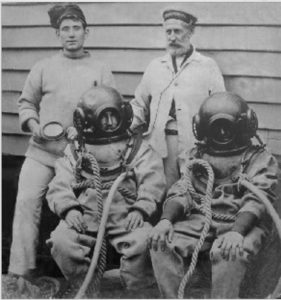

Echoing White Australia Policy mandates, grandiose reports of the newly-arrived White Divers exaggerated their collective diving prowess: they had different and more up-to-date scientific diving methods; could dive deeper; stay down longer; and were purportedly impervious to the rigours of diving paralysis, otherwise known as the bends. Assigned to four specially allocated Broome-based pearling lugger groups for the duration, the ex-RN men were keen to prove their maritime mettle, and none more so than their spokesman and the unofficial leader of the group, William Webber.

White Divers Group One

Well known amongst the British diving fraternity of the time, Webber was considered not only one of the best deep-water divers in Europe, but also amongst the most reliable in commercial diving and marine salvage operations. With recent experience diving for Spanish treasure, and deep pothole exploration in Africa behind him, Webber’s personal views were that pearl diving in Australia was easier because it was in shallower waters (roughly 20 fathoms or 36.5 metres), and in stable subsurface terrains.

He and his tender William Reid were contracted to Moss and Richardson’s vessel Eurus. Two days after arrival they put out to sea in the tail-end of the cyclone season. Whether they knew of the dangers remains open to debate, but either way Webber was keen to get on with the job. He was fully self-assured that anything the Japanese could do, he could do just as well if not better; this was a confident boast, but not one that lasted for long, because four months later it was Webber who was the first of the White Divers to succumb to the bends.

On 6 June 1912, he had been diving off the Kimberly region when Reid advised him to follow routine actions, including spending more time in staged surfacing. This was because the air breathing apparatus was not controlled automatically, and it was the only way Reid could successfully manage and safely control Webber’s decompression manually. Reportedly ignoring Reid’s advice, Webber ascended too fast, and after a fifth and final hour-long dive at an average depth of 18 fathoms (roughly 33 metres), he collapsed on deck, dying the next day.

Although Reid, the vessel owners and the crew were subsequently exonerated from any responsibility for Webber’s death, it cast a shadow over the entire premise of the Australian government’s investment. With Webber gone, the white experiment on Eurus abruptly ended. Reid found himself promptly re-employed into the downgraded onboard position of shell opener. The twin paradox was that both were immediately replaced by Asian contemporaries, and it was theJapanese doctor, Dr Tadashi Suzuki, from the Japanese built, Japanese funded and Japanese run hospital in Broome, who confirmed in his coroner’s report that Webber had died from the bends.

That Webber had died of conditions related to the same depth and conditions as other non-European divers sent the government into panic mode. As the finger pointing began, allegations were made that it was the fault of local pearling businesses, because they were withholding necessary support for the White Divers, providing substandard equipment, and not providing

meaningful instruction into methods and conditions of shell-harvesting. In any case it counted for little, because fractures were already appearing within the other teams.

White Divers Group Two

Ernest Freight, Fred Beesley, and their tender Harry Hanson fared somewhat better, working onboard Robison and Norman’s more technologically advanced vessel Ena. They also all believed that their success was assured, having already worked in similar depths to Webber, and they shared advanced naval training in retrieving objects overboard. This included subsurface anchor, cannon and gun recovery, sunken cargo removal, laying moorings, pier and breakwater building, and previously, general ship’s maintenance including cleaning underwater valves of ironclads.

All seemed to be going well until nearing completion of their contracts on 23 February 1913, when news reached Broome that Beesley had died at sea five days earlier. As far as anyone could tell nothing untoward had happened; all the equipment on board including the compressor was in good working order, and no fault had been found in either the diving kit or actions of other onboard personnel. Being weeks of sailing distance from Broome and lacking any refrigeration capabilities, Beesley’s body was reportedly taken ashore and buried in King Sound. Unlike Webber, there was to be no coronial inquiry.

White Divers Group Three

The next group of Fred Harvey, Stephen Elphick and their tender Charles Andrews worked on Sydney Pigott’s vessel Fran. Like their compatriots, they too were confident in their transferable skills, yet they collectively seemed to realise success was in learning as much as possible about immediate subsurface diving conditions. Sometime midway through 1912 Pigott appeared to have taken a dislike to Andrews, denigrating his sailing ability as less than an unskilled seaman, including ship handling. Using his alleged incompetence as justification, Pigott unceremoniously landed Andrews in Broome, replacing him shortly thereafter with local crew. Like Reid, Andrews soon found himself downgraded to onboard shell opener, while his fellow White Divers went on to fulfil their twelve-month diving contracts, seemingly without further incident.

White Divers Group Four

The largest and final group included divers John Noury, James Rolland, Reg Hockless and Stanley Sanders. All four were allocated to Sydney Pigott’s schooner Muriel, and all worked exclusively with highly experienced Asian and Aboriginal dive tender crews. Pigott appeared comfortable with that choice, possibly because his expanding pearling interests were already focused on harvesting the nearby, untouched deeper water area shell beds, including Roebuck Deep.

Within a month of arrival, they, like all the other White Divers bar Webber and Reid, had experienced their first devastating cyclone in March 1912. When the regular coastal liner from Fremantle, SS Koombana – the same vessel that had transported them all to Broome – was overdue, Muriel participated in the eight-day multi-vessel search and rescue (SAR) operation. When Koombana‘s wreckage was found, it was Muriel that was tasked with carrying the grim news back to Broome. The poignancy was that three female passengers of particular interest to Muriel’s skipper had been onboard. Some time during the devastating Westralian March cyclone in 1912, Pigott had lost his wife and his two step-daughters to the sea.

Whatever the conditions were onboard Muriel in the aftermath of mopping-up operations or Pigott’s tragedy is unknown, but it seemed relationships onboard were fracturing. Pigott was unhappy with their ongoing failures, especially in meeting minimum shell quotas. The White Divers were unhappy with pearling life, complaining both about onboard labouring and the monotonous repetitive work. Things came to a head in a heated argument between Sanders and Pigott in May 2012, when grievances were aired that this was not the type of work fit for ‘white men’. Pigott’s response was to put it in writing which Sanders promptly did, entering his complaints into Muriel’s ship’s log.

For reasons unknown Sanders later destroyed that page, which did not go unnoticed or unpunished by Pigott. As any sailor knows, a ship’s log is the book that records the life history of the vessel, and anybody who tampers with it is committing a crime. There was little chance that any of them would not have known that, even if it was a ship’s log from a little Australian pearling lugger in some remote backwater of the world, it remained an official document. Within days Sanders faced Broome court, admitted his offence, and was fined the princely sum of £20. Unable to meet the fine, he was arrested and jailed for one month, in response to which Pigott promptly released him from his contract, immediately replacing him with an Asian diver who worked alongside the White Divers until their contracts ended.

The Last of the White Divers: The Curtain Quietly Falls on the Great Australian White Experiment

By early 1913, when all of the contracts of the White Divers had expired, all surviving members – bar Sanders and Reid – had left Broome and the pearling industry for good. All of them had suffered diving-related injuries, and none of them had found a single pearl of value. Reid remained employed as an onshore shell opener for some time, although his later fate is still unknown. Sanders was to be the last of the White Divers in Broome. After his release from prison, he began searching for work anywhere in the pearl beds. By mid-August 1913, he found a temporary replacement diver position. After working for about a fortnight in 15 fathoms (roughly 27 metres), after his last dive on Sunday, 24 August 1913, he collapsed on deck and died.

The passing of Sanders quietly closed the curtain on Australia’s first and last White Australia Policy maritime experiment. A tragedy of twelve ex-RN men that in itself should be recognised as an integral part of Australian maritime history.

Select Bibliography

Affeldt, Stefanie. ‘The White Experiment: Racism and the Broome Pearl-Shelling Industry’, in Anglica An International Journal of English Studies, DOI: 10.7311/0860-5734.28.3.05 (accessed February 23, 2021).

Australian Government, Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (No. 17 of 1901) C1901A00017 https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C1901A00017 (accessed February 23, 2021).

Bailey, John. The White Divers of Broome, e-edition, Adobe ereader format 978-1-74197-804-9 [4605].

‘Broome Pearlers’, in The Register (Adelaide, SA), Saturday, 25 May 1912.

‘Diver Fined’, in The Register (Adelaide, SA), Thursday, 9 May 1912.

‘General News The Pearlshell Commission’, in The Queenslander (Brisbane, QLD), Saturday, 4 May 1912.

‘Interview with the Men’, in Broome Chronicle and Nor’West Advertiser (WA), Saturday, 24 February 1912.

‘Last White Diver Dies of Paralysis’, in The Age (Melbourne, VIC), Monday, 29 September 1913.

NAA: A1, 1913/13110 Returns and Statistics relating to the Indented Labour employed by the Pearling Industry – Broom (sic) 1912-1913 [45 pages].

NAA: A1, 1913/15429 British European divers and tenders for Pearling Industry [68 pages].

NAA: A1, 1938/2336 Preponderance of Japanese in Pearling. Question of Employment of other Races. Decision re Ratio of Nationality [348 pages].

Parliament of Australia, 4th Parliament 2nd Session of the House of Representatives, in Hansard, Thursday, 26 October 1911, https://historichansard.net/hofreps/1911/19111026_reps_4_61/ (accessed February 22, 2021).

Stride P. and Louws, A. ‘The Japanese Hospital in Broome, 1910-1926. A harmony of contrast’, in The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh, 2015;45(2):156-64. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2015.215. PMID: 26181534. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26181534/ (accessed February 23, 2021).

‘The Great Cyclone’, in The Register (Adelaide, SA), Wednesday, 27 March 1912.

Western Australian Government. Land Tax and Income Tax Act 1907 (No 16 of 1907), http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/wa/num_act/ltaita190716o1907247/ (accessed February 23, 2021)