- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

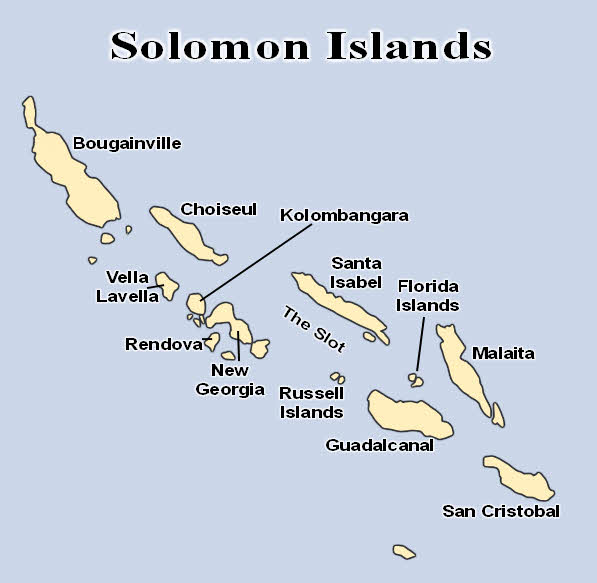

Tulagi is one of more than 900 islands and atolls in the nation of the Solomon Islands, a beautiful archipelago stretching over 1,400 kilometres in the Coral Sea. It lies to the north-east of Australia and counts amongst its neighbours Papua New Guinea, Nauru, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Fiji.

The largest of the Solomon Islands – Choiseul, Guadalcanal, Malaita and Makira – vary from 150 to 190 km in length and 20 to 50 km in width. On Guadalcanal, Mount Popomanaseu reaches 2,355 metres into the clouds, which is higher than Australia’s Mount Kosciuszko.

The islands have been inhabited for many thousands of years and the indigenous cultures are closely related although linguistically remarkably diverse. Dramatic change came in 1893 when the Solomon Islands were declared a British protectorate centred on the small island of Tulagi, which forms part of the much larger Nggela Islands, also known as Florida Islands.

Tulagi is only five km long and less than one km wide and comprises about 320 hectares. A natural advantage is a safe inner harbour. Originally forested, the island receives a high annual rainfall which supplies natural springs with plentiful fresh water.

Tulagi was the capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate (BSIP) from 1897 to 1942. A town was established here which later extended to neighbouring small islands. An Allied seaplane base was established before WWII. During the war Tulagi was heavily bombed, first by the Japanese and second by the Americans, erasing most reminders of its colonial history.

Before the Pacific War the permanent population of the enclave was around 600, comprising 100 Europeans, 200 other nationalities but mostly Chinese, and 300 Solomon Islanders. Tulagi was a poor cousin when compared with the much larger commercial centres of Suva and Rabaul. In many respects it mirrored the PNG island of Samarai in the China Strait which, although small in area, became an important administrative centre until deserted early in WWII, never again to rise to prominence.

After the war a decision was taken not to rebuild Tulagi and to move the capital to new administrative headquarters on Guadalcanal, making use of vacated American infrastructure. This became Honiara.

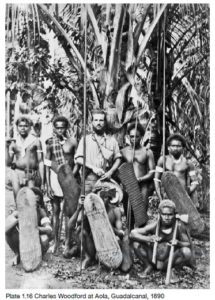

Charles Morris Woodford (1852-1927)

The first resident commissioner of the BSIP was Charles Morris Woodford. He was born in Kent, England, the son of a prosperous wine and spirit merchant. He developed a keen interest in natural history which led him to explore remote areas of the Pacific in search of specimens for museums and rich private collectors. In 1882 when aged 30 he gained employment as a government agent in Fiji, visiting outlying islands in the vessel Patience. He also gained a post with the Western Pacific High Commission (WPHC) Treasury.

Woodford returned to England where he sold his collection, which allowed him to make a further voyage to the Pacific studying as a naturalist while working from the labour trade schooner Christine. He also became interested in anthropology and wrote a successful book, A Naturalist among the Head-Hunters which became a standard text on the Solomon Islands. He then began to campaign for Britain to take formal possession of the Solomon Islands.

In 1889 Charles Woodford married Florence Palmer, the daughter of a pastoral family from Bathurst, NSW. They initially moved to London where he worked as a stockbroker. Bored, they returned to the Pacific and he again began lobbying for a new protectorate in which he sought to become resident commissioner. Woodford’s overtures were initially rebuffed but eventually in 1896 the Colonial Office acquiesced.

Whalers had operated in the Solomons since the 1790s with their presence declining by the 1860s. They were followed by European traders who came from Sydney, mostly to buy copra, ivory nuts, bêche-de-mer and turtle shell. The Norwegians Julius Andersen and Lars Nielsen were prominent amongst these traders who established outposts in the islands.

Charles Woodford chose Tulagi as the headquarters for the BSIP. Missionaries had established Christianity in the region from the 1860s and local people would provide labour in exchange for manufactured goods. Andersen and Nielsen had also established trading stations here. And from the 1870s Tulagi became an important outpost in the labour recruiting trade between Australia, Fiji and the Pacific Islands.

Not all proceeded smoothly, and in 1872 the crew of the schooner Lavinia was massacred at Gela while the ship was anchored collecting bêche-de-mer. Most infamously, on 12 August 1875, while trying to conciliate differences on the Santa Cruz Islands, Commodore James Goodenough, the Commander in Chief of the Australia Station, was wounded by a poisoned arrow. He refused to allow a single life to be taken in retaliation. The Commodore died a few days later in his flagship HMS Pearl while making for Sydney. In 1880 the commanding officer of the schooner HMS Sandfly, Lieutenant Bowers, and three of his crew were massacred while ashore on the Florida Islands. In retaliation HM Ships Cormorantand Emerald from the Australia Station were sent on a punitive expedition, destroying villages, canoes and crops.

To spread the word of the newly proclaimed protectorate and to comply with specifications requiring acceptance by indigenous leaders, a Royal Naval expedition was dispatched from the Australia Station, comprising the corvette HMS Curacao (Captain Herbert Gibson) and the gunboat HMS Goldfinch (Lieutenant Henry Floyd). These ships visited the Solomons in June and July 1893. They landed about thirty times, and at each stop the commanders hoisted the Union flag, ordered a feu de joie and read a proclamation.

On 28 June 1893, Curacao visited Port Curtis at the southern entrance to the Florida Islands, transiting the narrow strait between the two main islands, and landed at Siota, the headquarters of the Melanesian Mission. Here Captain Gibson met the local ‘big-man’ Joseph Havousi, explaining that the islands had been declared a protectorate. A locally based missionary the Reverend Richard Comins accompanied the ship to Malaita and other islands, helping to explain the process at each stop. Not all went to plan as at Makira a bombardment was sanctioned in retaliation for the death of a crew member of the Queensland labour vessel Helena. And at two other islands the local big-men refused to touch the proclamation document or accept gifts, and at another island the locals immediately ripped up the Union flag to make loincloths.

To take up his new position of Deputy Commissioner of the Solomons Protectorate, Charles Woodford arrived at Tulagi in May 1896 aboard the sail/steam sloop HMS Pylades. He then toured the islands and mounted a punitive expedition in Guadalcanal to avenge the deaths of Austrian Baron von Norbeck and members of his expedition. He next established a temporary headquarters at Nielsen’s trading station on Gavutu Island, five km from Tulagi.

Woodford had known Nielsen since his first visit as a naturalist and had always enjoyed his hospitality. His initial report said that there were 48 Europeans in the Protectorate, four of them missionaries, and 21 trading vessels. Primary consideration for a permanent settlement was for a sheltered port, and both Tulagi and Gavutu harbours were suitable. Tulagi was best positioned for travel to other islands, only 25 km from Guadalcanal (the largest island) and close to Malaita (the most populous island). However, Tulagi’s soils were poor and the island was uninhabited.

Using Nielsen as a broker, Woodford purchased Tulagi from local owners, paying £42 in gold sovereigns, with the deal being concluded on 29 September 1897. His appointment as Resident Commissioner was confirmed on 17 February 1897. He was given £1,200 as a grant-in-aid, and a salary, on an understanding that the protectorate became financially independent as soon as possible. He was also directed to control the labour trade and stop an illegal trade in firearms.

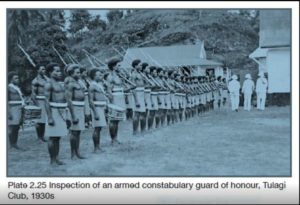

Establishment of Administration

In March 1897, Woodford joined HMS Rapid which took him to Gavutu, and then to the western Solomons to investigate the deaths of several traders. He employed Gela villagers to cut tracks across Tulagi and clear sites for the residency and police barracks, and to cut timber for buildings and remove mangroves to establish a jetty. From late June 1897 Woodford and five prisoners plus three labourers lived permanently on Tulagi. Soon afterwards HMS Torch arrived from Fiji with the first members of an armed constabulary. They were eight Solomon Islanders who had worked as policemen in Fiji for some time. Amongst other duties they served as crew on the Commissioner’s whaleboat.

Civil administration was set up starting in the Florida Islands, which were divided into five small districts, each under a chief responsible to Woodford. This political arrangement was welcomed by the Anglican Mission there. Woodford’s resources were still limited, however, and for major assistance he had to rely on ships sent by the Royal Navy. In 1910, when three missionaries were killed on Rennell Island, the most southerly of the Solomons, his only recourse was to close the island to outsiders, and when a murder was committed on Malaita, he had to appeal for Torch to be sent to make a punitive raid.

Much of the interest in capital investment that Woodford sought was diverted to Banaaba (Ocean) Island, when its rich phosphate was discovered in 1900. However, Arthur Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Baron Stanmore, who Woodford had been able to interest in commercial investment in the Solomons, persevered with his plans, buying German landholdings and trying to amass enough capital for large-scale coconut agriculture. In 1905 that land was sold to Lever’s Pacific Plantations, and the rent it provided for the protectorate enabled the government to expand.

Woodford established the first regular mail service between the islands and the outside world using Burns Philp steamers plying to Sydney. Woodford even designed his own postage stamps of the ‘Canoe Series’ which produced a considerable income in a world that was then full of postage stamp collectors. These stamps are now rare, and unfortunately there are many forgeries.

Woodford, worried that the Melanesians were a dying race, supported a plan to import labourers from India, but this was refused by the India Office. The development of local plantations coincided with the end of the labour trade in Queensland, and the difficulties caused by the repatriation of the workers under the White Australia policy was predicted by Woodford.

In 1907 Woodford’s health failed, most likely through a severe case of malaria, and he was hospitalised in Sydney. It left him debilitated and often lacking that spark of vitality which for years had been his trademark.

Woodford left the islands in January 1914. By that time the islands were largely pacified, and head-hunting had nearly died out. New Georgia and Malaita remained troubled areas, but a district office on the latter, at Auki, was established in 1909. However, after Woodford left, much of his progress was undone. After his departure the protectorate government never regained the initiative that it had while under his control. Charles Woodford retired from public life in 1915 at the age of 63, when he and his wife found a rural retreat near Horsham in Sussex where he died on 4 October 1927. Charles Morris Woodford is remembered as a remarkable and energetic man who with a staff of four became the virtual ruler of a group of exotic islands with over 100,000 rather wild inhabitants. In often difficult circumstances, requiring naval intervention, the islanders generally prospered under his wise leadership.

HMAS Adelaide and the Malaita Expedition

Woodford would have been horrified by the events that occurred at the time of his death. These started when the District Officer for Malaita, William Bell, accompanied by Patrol Officer Kenneth Lillies and 15 native police arrived at Sinalagu (Diamond) Harbour to collect the hated annual head tax of five shillings per person. Islanders were obliged to work on plantations to pay the tax, and resistance to payment resulted in a violent confrontation with the death of both officers and nine police. This caused an uproar in Tulagi, in the belief that this could be the start of a full-scale uprising. A request was sent via the British Colonial Office for a warship, and HMAS Adelaide sailed from Sydney on 10 October 1927.

The punitive expedition in tracking down those responsible led to the deaths of about 30 natives, and about 170 were shipped to Tulagi for prosecution. Of these, 30 died of disease while in custody and six were convicted of murder and executed, with others receiving lesser charges. The Adelaide Expedition is seen by many as a dark day in colonial administration.

Development prior to WWII

An important development occurred on 4 November 1926 when a de Havilland DH50A floatplane flown by Group Captain Richard Williams RAAF (later Air Marshal Sir Richard) landed at Tulagi as part of a survey of the South Pacific as a potential theatre of operations.

In October 1935 the cruiser HMS Sussex, then on loan to the RAN, called at Tulagi during the Australian Squadron Spring Cruise throughout the South Pacific. Ironically as it turned out, the flagship HMAS Canberra and her destroyer escorts visited Papua New Guinea leaving the Solomons and other far-flung outposts of Empire to the Royal Navy.

With the Great Depression, little of significance occurred in the Pacific Islands other than a consolidation of the plantation industries under large British and Australian companies, at the expense of individual owners. A newspaper article announcing the arrival of a new Resident Commissioner for the Solomon Islands, Mr William Sydney Marchant, in April 1939, notes the protectorate is poverty-stricken with the Resident Commissioner subject to Suva, with which there was no community of interest, and he could do little.

But a renewed interest in these remote regions was under way. At the instigation of the New Zealand Government, from 14 to 26 April 1939 a Pacific Defence Conference was held in Wellington. This now long-forgotten footnote to history was important as it acknowledged the possibility of a Japanese attack against Australia and New Zealand and the Pacific islands. The conference was attended by the New Zealand Prime Minister Mr Michael Joseph Savage, the newly arrived British High Commissioner to New Zealand Sir Harry Batterbee, and the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific Sir Harry Luke. But owing to the recent death of its Prime Minister Mr Joseph Lyons on 7 April, Australia had no political representative, and it was attended by the Chief of Naval Staff, Vice Admiral Sir Ragnar Colvin RN.

Resulting from this conference patrol aircraft were to be provided to warn of Japanese intentions. New Zealand was tasked with aerial patrols of Tonga, Fiji and the New Hebrides, while Australia was responsible for New Guinea and the Solomons. New Zealand undertook to establish an air base (Nandi) in Fiji and a seaplane base near Suva. It also dramatically increased aviation training and the size of its air force. Australia, with the loss of its Prime Minister a major distraction, was preoccupied with the defence of New Guinea. However, garrisons of Australian and New Zealand troops were to be provided at various Pacific islands.

Sir Charles Burnett, Inspector-General of the RAAF, visited Tulagi by seaplane in May 1939 and recommended that Australia establish an advanced operational base here with fuel, water, communications and a small medical facility. This was largely undertaken using local resources. In July 1941 the RAAF moved 25 personnel from 11 Squadron RAAF operating out of Port Moresby to a new seaplane base at Gavutu-Tanambogo (close to Tulagi) with 4 x PBY Catalina maritime patrol aircraft. In the same timeframe 24 troops from the Australian Army 2/1st Independent Company at Kavieng in New Ireland were moved to the new base where they prepared anti-aircraft defences and helped train a local militia force. In addition, there were a number of coastwatchers throughout the Solomons, including three on Guadalcanal.

The War comes to Tulagi

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, planning took place for the evacuation of civilian staff from Tulagi and this commenced in mid-December 1941. Enemy intentions were telegraphed when they began bombing the settlement on 22 January 1942. As a result, the Resident Commissioner ordered the evacuation of Europeans to Australia and relocated his headquarters to temporary facilities on Malaita. Bombing raids intensified in April, and on 1 May one Catalina was damaged; the remaining aircraft departed on the same day. Australian Army and Air Force personnel embarked in two small ships on 3 May and made it to the safety of Vila in the New Hebrides.

Within hours of the Australian escape Japanese forces arrived off the island in four warships and six seaplanes, and unopposed landed troops mainly of the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Party. The very next day, on 4 May, three air strikes were delivered on the Japanese ships and shore facilities by aircraft from the carrier USS Yorktown. There was some damage to Japanese ships and aircraft and 87 men were killed. Despite this setback the Japanese expanded the facilities that had been left by the departing Australians.

On 6 July Japanese transports arrived off Guadalcanal, delivering materials and the first of 2,200 Korean and Japanese construction workers together with 500 troops to commence construction of a large airfield at Lunga Point. These activities were observed by American reconnaissance aircraft and coast-watchers. Alarmed at these developments which directly threatened Allied supply lines across the Pacific, the Americans planned a massive counterattack, resulting in a series of battles which decided the course of the war in the Pacific.

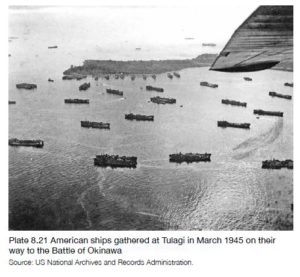

The Americans began massing their counter offensive in New Zealand, then home to the 1st US Marine Division. On 22 July they sailed in a task force from Wellington in numerous transports escorted by a combined US – Australian force of cruisers and destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley, VC, DSC, RN flying his flag in HMASAustralia. Distant cover was also provided by US carrier groups. Following rehearsals at Fiji, the task force split into two groups with one group heading for Tulagi and the major attack group heading for Guadalcanal. As poor weather had masked their approach the enemy were taken completely by surprise when their shore positions were bombarded just before dawn on 7 August. As the day progressed Japanese air attacks were received with increased intensity but overall, casualties to both men and ships was light.

In the first major amphibious action of the war 3,000 marines landed on Tulagi and 11,000 marines on Guadalcanal. The Japanese on Tulagi were heavily outnumbered and were killed almost to the last man. The bitter battle for Guadalcanal took six months and continued until 9 February 1943 when the Japanese, who had suffered devastating casualties, evacuated the remainder of their forces.

This paper does not attempt to analyse the Guadalcanal campaign, but in many respects it was closely contested with the Americans losing 29 ships and 615 aircraft against Japanese losses of 38 ships and 683 aircraft. But as telling as these figures are, the Japanese death toll was 19,200 compared to the American number of 7,100. Most importantly, the Americans had the resources to replace their losses in materials and manpower whereas the Japanese had exhausted their reserves.

The Battle of Savo Island

There is one battle in this campaign which should be mentioned as it is welded into the Australian psyche and especially into the history of the RAN: The Battle of Savo Island.

Immediately following the American offensive, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa in charge of the Japanese fleet at Rabaul devised a high-speed night attack proceeding south of Savo Island to penetrate and torpedo the enemy force at Guadalcanal and thence bombard Tulagi. Night transits through the New Georgia Sound (nicknamed the Slot) became a famous feature of Japanese naval warfare in this region.

The battle which took place in the early hours of 9 August 1942 was a resounding success for the aggressor and a tragic loss for the defenders under Admiral Cruthchley’s command. The Allied losses included four heavy cruisers sunk (including HMAS Canberra) and considerable damage to other ships, and the loss of over 1,000 men and over 700 wounded. There was no major damage to Japanese ships and minimal loss of life. After the action, fearing a dawn air attack (which did not eventuate), Admiral Mikawa withdrew his forces. Savo was therefore not a decisive battle, but it might have been had the Japanese pressed home their advantage against the American transports with all their marines.

The wreck of Canberra lies in Iron Bottom Sound, also the resting place of 31 other Allied ships lost in this conflict. The wreck is said to be surprisingly intact and remains a memorial to the 84 men who died, including Captain Frank Getting RAN, and the 626 survivors.

A little Island with a big History

In many respects the more recent history of the Solomon Islands revolves around the small and now insignificant island of Tulagi which for many years was the nation’s capital and the catalyst of major events in the Pacific war. What remains of its big history is surely worthy of preservation!

References

Date, John, C., Naval Battles in the Solomon Islands – August to November 1942, Monograph 149, Naval Historical Society of Australia, Sydney, 2001.

Kwai, Anna Annie, Solomon Islanders in World War II – An Indigenous Perspective, ANU Press, Canberra, 2017.

Lawrence, David Russell, The Naturalist and His ‘Beautiful Islands’: Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific, ANU Press, Canberra, 2014.

Millar, T. B., Australia in Peace and War, 2nd edition, ANU Press, Canberra, 1991.

Moore, Clive, Tulagi: Outpost of British Empire, ANU Press, Canberra, 2019.

Morison, Samuel Eliot, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol 5, McClelland and Steward, Canada, 1949.

Pacific Islands Monthly, 17 April 1939, GPO Sydney.