By Bob Hetherington

The following story was first published in the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) Volunteers’ Quarterly newsletter ‘All Hands’, Issue 112 in September 2020.

Some dreamers always maintained that Artic waters could offer a faster way across the globe. So, were they right?

The Dream

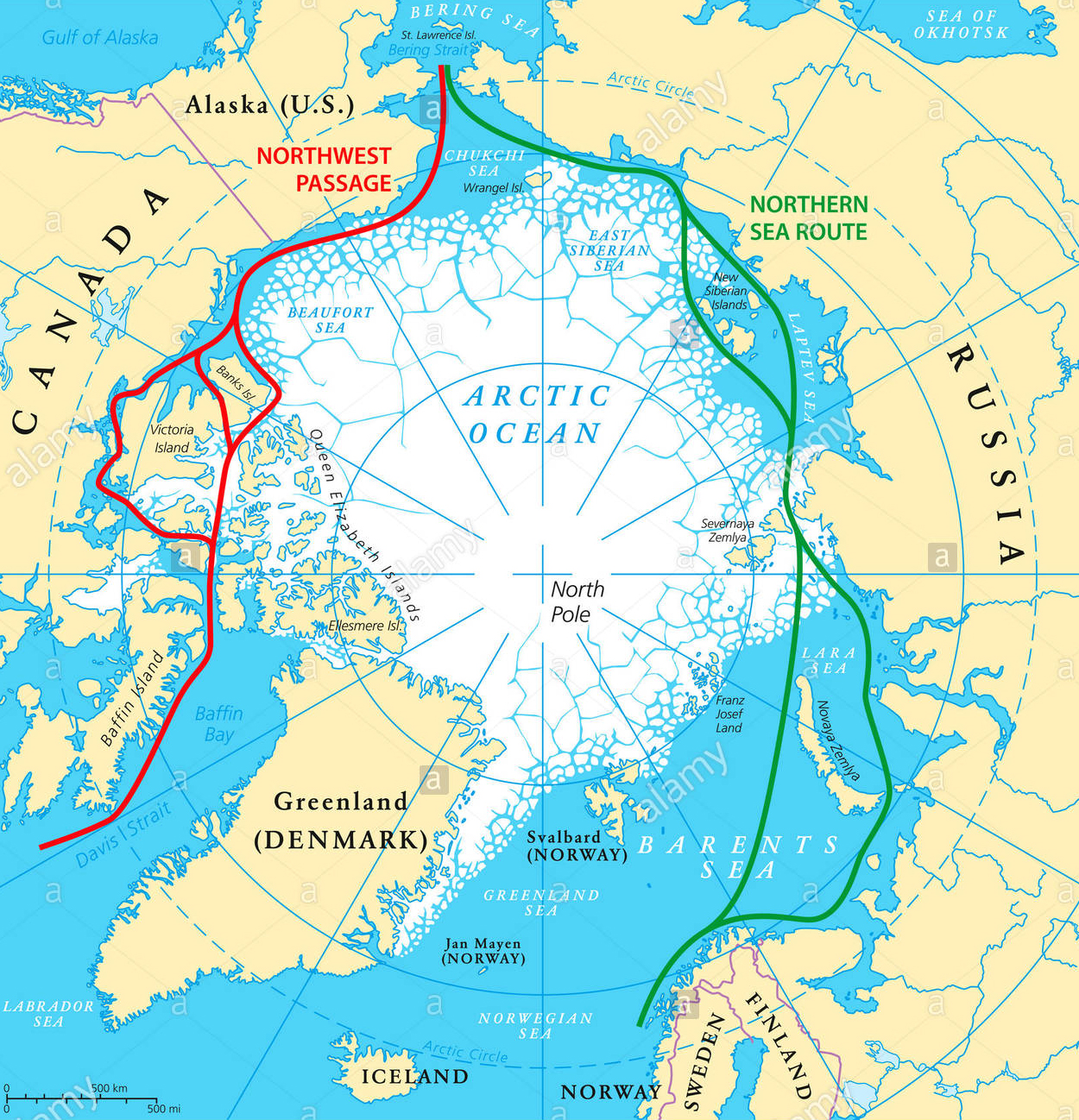

From the time of Columbus Europeans dreamed of a sea route westward to China and the riches of the Orient. As they slowly charted the coasts of North and South America they found no easy passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Magellan demonstrated the distances and challenges of the southern route and the Panama Canal was centuries in the future so they pondered the possibility of sailing across the top of North America. Attention turned to a search for a “Northwest Passage” from the North Atlantic to the Pacific.

After the British gained possession of the territory of modern-day Canada they led the European push to find such a passage, starting from the east coast of Canada and exploring westwards by sea and land. It was a frustrating process: they found no exit from Hudson Bay to the west and turned their attention to Baffin Bay, beyond which lay a frustrating maze of islands. Dominating everything was the climate, they could only explore during the summer months and were forced to camp for the hostile and often deadly winter.

This meant that expeditions were away from home for two and three years at a time. Of the many expeditions from the 17th to the 19th century the largest and best equipped ended in the most spectacular failure. In 1845 Sir John Franklin (a former governor of Tasmania) led a mission with two ships and 129 men. They reached a point approximately two thirds way from east to west then disappeared, there were no survivors.

Later expeditions reached further westward constantly impeded by ice, shallow water and confusing geography. At last, in 1903 legendary polar explorer Roald Amundsen set out from Oslo to prove the Northwest passage. In a tiny sloop-rigged “fishing smack” named Gjoa with a small auxiliary motor and a crew of six he initially followed Franklin’s route. His choice of vessel was a wise one. With its manoeuvrability and shallow draft it was able to negotiate the ice effectively. He proceeded into the unknown and eventually reached the Beaufort Sea, having traversed the “missing link” of the infamous Northwest Passage. Amundsen’s story makes gripping reading and is well told by James P. Delgado in his book “Across the top of the world”[i].

The next transit was not until 1939 by RCMP vessel St Roch, from Vancouver to Halifax, requiring two winter camps and the use of explosives against the ice. In 1954 HMCS Labrador passed from east to west and in 1969 the 155,000 ton tanker SS Manhattan refitted as an icebreaker and escorted by an icebreaker also made the passage. At the time of publishing his book in 2,000 Delgado summed up the situation: The fabled Northwest Passage, so many centuries in the finding, in the end proved neither a fast road to the riches of the Orient, nor an easy route for the explorer seeking fame.

The Dream continues

There is a parallel story here: the objective was the same but the means were different. While some Europeans dreamed of a north west passage to the riches of the Orient others wondered whether their ships might sail from west to east along the northern coasts of Russia into the Pacific. In 1553 English navigator Hugh Willoughby entered the Barents Sea (NW Russia) and sailed some way east before turning back. During the 17th century traders were using a sea route from Archangel in the west to the Yamal Peninsula, less than one third of the way to eastern coast, and in 1648 a Russian navigator sailed the eastern end of the passage to the Bering Strait. The central section of the sea route remained unexplored until in 1878-79 Swede, Adolf Norgenskjold sailed the entire passage from west to east. He nearly succeeded in completing the voyage in a single season but was stopped by ice and forced to winter just short of the Bering strait.

Russian politics delayed the development of the Northeast Passage until in 1932 a Soviet expedition sailed from Archangel in the west to the Bering Strait in the east. By 1935 the route, now designated Northern Sea Route (NSR), was officially defined and opened for commercial exploitation. After the collapse of the USSR traffic declined and a shipping expert opined that “mainstream container shipping will overwhelmingly use the Suez route but niche activities like bulk shipping will grow along parts of the NSR due to mining and resource development.”

After centuries of struggle, frustration, loss and death it seemed both passages had become little more than geographical curiosities.

The Reality

The reality of viable commercial Arctic routes between Europe and Asia has taken on new life in recent years. Ice, the age-old obstacle, appears to be loosening its grip. Since the early 2000’s the extent and thickness of ice on both passages has significantly reduced and governments and shipping operators are re-examining commercial potential. The savings in distance compared to conventional routes remain alluring: the Norther Sea Route (NSR) between northern Europe and Shanghai is 5500 km shorter than the Suez route. Using the Northwest passage saves around 4000 km compared to Panama. However, distance alone doesn’t tell the whole story, it does not always translate into time saving which varies according to ice conditions.

The macro picture of ice has been available from satellite imaging for almost three decades, but the micro picture is much less clear and can change quickly. Navigability at every point is difficult to forecast and makes planning of commercial traffic risky. In any case for the foreseeable future complete transit by larger vessels will be possible only in the summer months with the time window varying from season to season. Nevertheless, trial voyages have been made recently in an attempt to assess potential more accurately.

In the summer of 2018 Danish shipping giant Maersk sent Venta Maersk, a mid-size container ship from Busan South Korea to Bremerhaven via the NSR with a commercial cargo on a one-off trial. Afterwards Maersk denied any intention to develop a service and said it would continue to use conventional routes. In June 2019 it announced a plan for a second voyage suggesting interest in the NSR was still alive but at the time of writing there were no reports of the second voyage taking place.

More recently a Russian operator sent a small container ship Sparta III from China to Europe on the NSR, claiming a saving of 10 days compared to Suez. The company’s website claims this vessel “operates a commercial service sailing from Shanghai…during the summer navigation period from August to October the NSR is optimally short and fast…”

Recent activity on the Northwest Passage is more difficult to interpret. Here, too, one-off commercial voyages have been made: In the summer of 2013 Nordic Orion took a cargo of coal from Vancouver to a Finnish port, requiring some icebreaker assistance. It saved four days compared to Panama and according to the operator $US 200,000 in voyage costs. In 2014 Nunavik, an icebreaker bulk carrier took a cargo of ore from northern Quebec to northern China.

A major consideration for ship owners is that to use these passages their ships may have to be designed to a special Arctic code involving higher investment per tonne of cargo. Nunavik is designated Polar Class, capable of independent operation in harsh Arctic conditions, but ships built to lower specification may require expensive icebreaker escorts in these waters. There is a harsh contrast here with the temperate Panama and Suez routes and their well-established infrastructure, easier navigation and emergency resources.

In August 2018, the Russian research-cruise vessel Akademik Ioffe with 126 people on board ran aground in the Northwest Passage. All were safely rescued but one passenger, Edward Struzik reported on the dangers and the luck of the rescue. In an article headed “As ice recedes the Arctic is not prepared for more shipping traffic” he concludes “…there are few signs that shipping companies are in a hurry to exploit the shortcuts that the Northwest Passage offers between the Atlantic and the Pacific.”

The real reality

All the resources and human ingenuity devoted to these efforts in the future will succeed or fail according to those same forces of nature which dogged the past: temperature and ice.

In terms of the early dreams, an ocean highway linking the world’s greatest oceans, the reality has fallen short. Both Arctic routes are far from highways, they are more like unmade country roads…open for brief and unpredictable periods, potentially dangerous and requiring exceptional skill in the traveller. The upgrade to a maritime highway is in the hands of Mother Nature. If present climate trends continue the upgrade will occur and the traffic will grow. Sadly, if the highway does materialise, conditions on the planet may be such that shipping routes will be the least of mankind’s concerns.

[i] Delgado, James P., Across the top of the World: The Quest For The Northwest Passage first published 1999 by Douglas & McIntyre Ltd Vancouver www.theconversation.com