- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Naval Technology

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Geoff Davidson

In 1994 I was posted for three years to Washington DC as the RAN representative to provide weapon and ship follow-on support for the FFG ships HMA Ships Adelaide, Canberra, Sydney, Darwin, Melbourne and Newcastle. This posting wasbased in the US Navy headquarters in Washington and was unique in that no other country was allowed to have itspersonnel based in and as part of the US system (other than exchange officers). I was required to support RAN equipmentand advise on technological developments.

The significance of this position was that it was two hatted, as I worked as a US Defence Department civilian, in an American office with an American boss and American co-workers. But, as was obvious to all, I was foremost an Australian and an RAN representative. This allowed me almost unrestricted access throughout the USN offices andmeetings, and often to meetings where all foreigners were excluded except myself. I was therefore able to hear about andtake action on issues to our advantage that in the normal way we would never be aware of.

I should state that Australians and Australian Defence personnel still have a wonderful and well respected reputation inAmerica. I’m convinced that our historic, sometimes controversial alliance has cemented the existing strong relationship.One of my tasks was to procure ammunition fuses from the US Navy, based in Crane, Indiana (south of Indianapolis).During a visit to this facility I was invited to tour their ammunition manufacturing facilities and their museum.

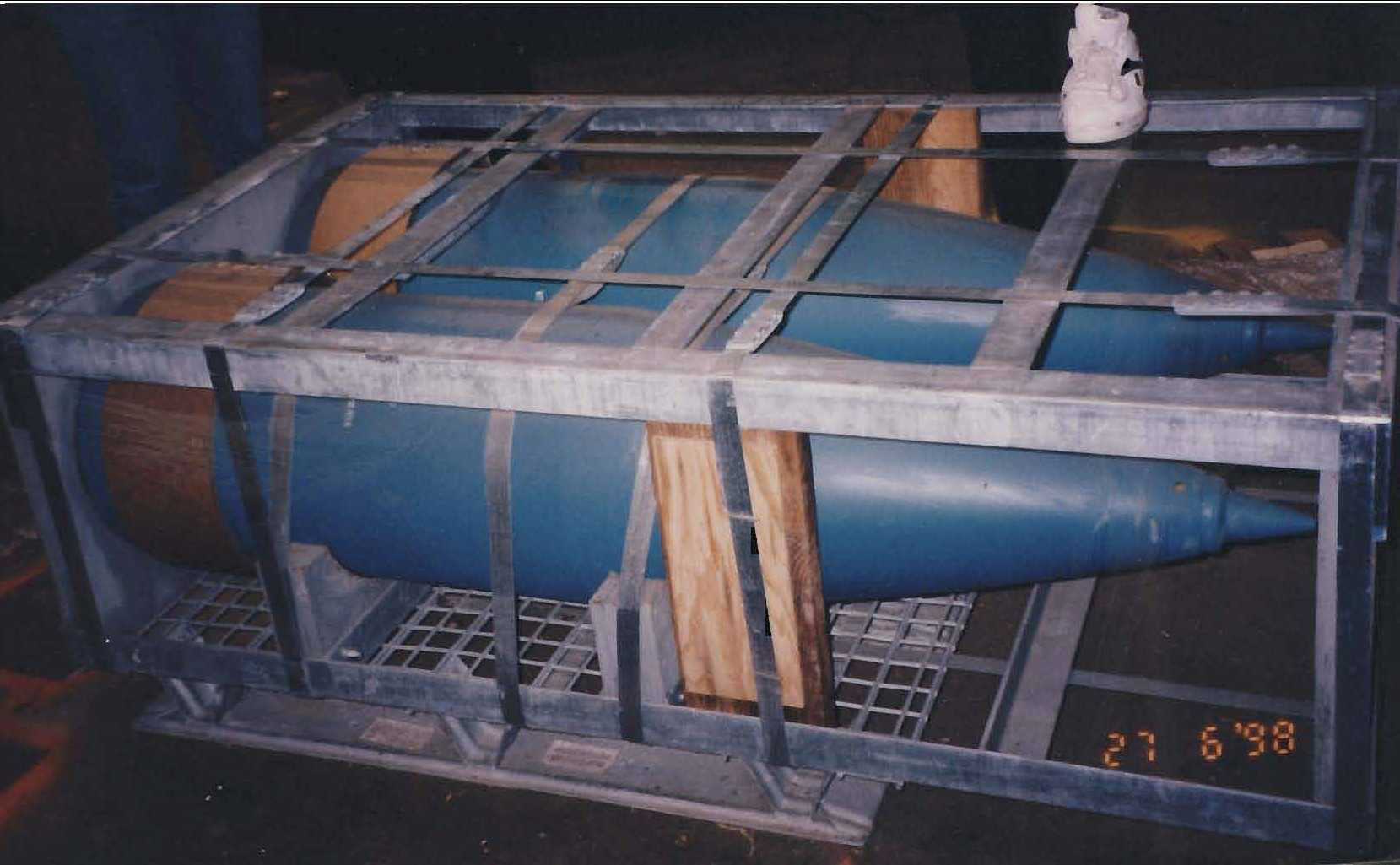

In this museum was an example of an Iowa class battleship’s 16-inch projectile. A sneaker provides relevance of its size. Six bags, each containing 110 lbs of propellant, are required to provide the motive force to drive the projectile towards its target. The distinctive blue colour of these particular projectiles denotes they are inert rounds known as BL&P – Blind Loaded & Plugged.

Standing almost head high to myself, it is easy to be overawed with the sheer size and power. Staring into history, theUSN had decided to decommission these ships, thus ending an era that had lasted from 1945 to 1992 (over 47 years). These battleships had operated throughout WWII, memorably with the Japanese surrender signed on USS Missouri; they also served in Korea, Vietnam, Lebanon and finally the Gulf War. Their main armament was the 16-inch/50-calibre Mk 7 gun. There were nine of these housed in three triple turrets. In layman’s terms the guns had a 16 inch bore and were 50 calibres long or 66.7 feet from the chamber to the muzzle. Each turret required a crew of 79 men to operate it.

When the USN recommissioned its four battleships during the Reagan presidency in the 1980s, the following quotewas made by Soviet Fleet Admiral Sergei Gorchakov, after watching USS Iowa in a NATO exercise:

You Americans do not realise what formidable warships you have in these four battleships. We have concluded after careful analysis that these magnificent vessels are in fact the most feared in your entire naval arsenal. When engaged incombat we could throw everything we have at those ships and all our firepower would just bounce off or be of little effect.Then when we are exhausted, we will detect you coming over the horizon and then you will sink us.

Many Australian ships have operated with these mighty ships and RAN personnel have sailed in them. Again, manyAustralian defence personnel have seen these ships in areas of conflict and noted their devastating effect. They are unique as the last of an era of old style big gun major capital ships. I should also like to recount what a current work colleague andex-Vietnam sailor told me about USS New Jersey when stationed near Nui Dat.

I was aboard HMAS Sydney as an engineering artificer. During the night when the USS New Jersey was firing over thehorizon, we could neither see the ship nor hear the guns. However, no one could miss her guns firing as the glow in nightsky was unmistakable. During the day, our old ship radar would pick up the shells in flight after firing, and the ship’scompany would be given a bearing to look for the shells in flight. Those were the only shells big enough that I was able to see in flight with my own eyes. The shells were equivalent in weight to firing a Volkswagen. I’m glad I was not at thereceiving end. I also remember that USS New Jersey was used for making a clearing in the jungle for helicopter medivacflights. One shell would be fired to clear the jungle. By the time the ground troops made it to the clearing, the helicopterswould be arriving to land. The USS New Jersey’s ship’s motto of “FIREPOWER FOR FREEDOM” was appropriate.

I was sure there were little or no relics of the battleship era, and these battleships in particular, preserved in Australia. These redundant projectiles were a most practical and graphical reminder of the sheer power they once represented and many former Australian sailors and service personnel would appreciate them being preserved as part of our maritime andmilitary history.

A few of the statistics of these projectiles and the ships that carried them are:

Ships – USS Iowa BB61, USS New Jersey BB62, USS Missouri BB63, USS Wisconsin BB64

Displacement 57,540 tons

Propulsion 254,000 shaft horsepower

Speed 34.7 knots

Projectile size 16-inch dia x 5 ft long

(406 mm x 1.524 m)

Projectile weight (light) 1,900 lb (848 kg)

Projectile weight (heavy) 2,700 lb (1,205 kg)

Projectile range 42,000 yds max

All four ships have now been preserved as museum ships, two on the east coast and two on the west coast of the United States. Missouri is now moored as a museum near the USS Arizona Memorial in Hawaii. New Jersey is a museumat Camden, New Jersey, Iowa a museum ship in Los Angeles, and Wisconsin a museum ship in Norfolk, Virginia.

To continue, further discussion with the ammunition depot established that these projectiles were being passed to selectedmuseums in the USA with the remainder to be scrapped.

The first part – getting approval

Needless to say, I decided we just had to try and have some of these projectiles for Australia. The USN response was that I could get some if the paper work and permissions were granted, but they doubted that this would be forthcoming. Thebest thing that happened was being told I would never be able to do it. Some statements cannot go unchallenged.

The advantage of being part of and treated as a US Defence staff member came into play. Many letters, with manydrafts, were forwarded to the US Navy International Programs Office (NAVIPO) seeking release. None of this formallyinvolved the embassy or the RAN, as bureaucracy was the last thing needed. Of course, the Australian Embassy and RANwere informally aware of discussions. After three months the USN finally approved release.

The second part – the transport problem.

How to get nearly ten tons of inert ammunition back to Australia. Fortunately, the Australian Embassy in Washingtonruns a freight section for shipping government and defence items to and from Australia. The section head agreed that theprojectiles were indeed of historic relevance and he agreed to provide transport back to Australia. The US Navy thendecided that we could not have trucks other than US Government contracted trucks enter the restricted base. So I hadpermission to take the projectiles, but no way to go in and get them.

The third part – the US Army.

Staff selected for these overseas postings are required to be proactive and do what is necessary to achieve the goal. After negotiation with both the navy base and US Army transport, the US Army agreed to transport the projectiles to SanFrancisco for nothing, nil, and nought, and with compliments to Australia. Wonders never cease.

The fourth part – the shells arrive

I had returned to Australia in December 1997, however the projectiles were still in the USA and it was necessary to keepthe process rolling. After further prodding with the freight forwarder in San Francisco, the projectiles arrived early 1998.Now if any of you have ever dealt with large defence supply stores, you would know that the last thing you want is for unique and special items to go into them. At times I swear there is no larger a black hole than a defence store. Therefore, Iintercepted the shipment and had them transported direct to a friendly contact in a warehouse at Garden Island naval basein Sydney. From here the projectiles were planned for distribution as follows:

Australian Maritime Museum Darling Harbour

Naval Heritage Centre Garden Island

Naval Aviation Museum Nowra

Naval Ordnance Museum ex-RANAD Newington

Naval Training Establishment HMAS Cerberus near Melbourne

Australian War Memorial Canberra

Royal New Zealand Naval Museum Auckland

Pay’s Warbirds Museum Scone

Camden Museum of Aviation Narellan

Cowra War Museum – my home town

When deciding to obtain these projectiles I had no idea how many to ask for, other than keeping the number smallwould have a greater chance of success. Ten seemed to be the right number. So if you come across an ex USN 16-inch gun projectile during your travels around our country this is most likely its story.

Geoff Davidson: Career Summary

A brief summary of Geoff Davidson’s career may interest our readers and in another edition of this magazine we intended to run an article on his apprenticeship training.

On Monday 7 January 1974 Geoff started his working life as an apprentice fitter and machinist at Garden Island Dockyard. Simultaneously he started a four-year Mechanical Engineering Certificate course. On completion of this rigorous training he became a Trainee Technical Officer – Naval Systems.

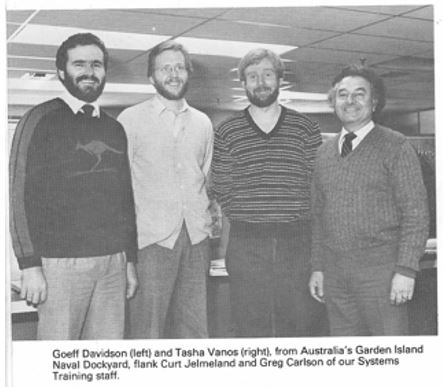

In 1981 Geoff was sent to Chicago Naval Training Base for a six-month Guided Missile Launcher System (GMLS) Mk 13 operator and maintainer course, followed by six weeks training with the manufacturer, FMC, in Minneapolis. On return to Garden Island he put this training to good use as a maintainer of the new FFGs.

In 1983 it was back to Minneapolis for a further six weeks of training for the conversion and upgrade of the older missile launchers in our three DDGs. During this period, he was promoted to Senior Technical Officer Grade One and became the Project Manager for the upgrade and overhaul of the missile launchers.

In 1989 it was off to Canberra joining the FFG ship Helicopter Modification project. While here he completed anAssociate Diploma in Applied Computing.

In mid-1994 he was selected as the RAN FFG Combat and Weapons systems representative based with the USN in Washington for three years. Upon return in late 1997 he was promoted to Acting APS Senior Officer and took up a new position as Configuration Manager in the ANZAC ship project until end 1999.

In early 2000 he spent one year in Acquisition Policy advising on the development of new projects. After this he undertook a Defence Project Manager and Development Program and on completion received a Master’s Degree in Engineering.

In 2002 this led to a position as Project Manager for development of new projects in the Surveillance & Control Branch, Electronic Weapons Systems Division. In mid-2003 there was a one-year secondment to the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet – National Security Division, preparing briefs on new weapon system projects. Geoff returned to project management in the Defence Department in August 2004 and remained there until ill health obliged him to take early retirement in February 2012.