- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, Aviation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Max Speedy

This article first appeared in the June 2022 edition of the RAN Fleet Air Arm magazine Slipstream Vol 33 No 2 and is reproduced by kind permission of the author and the editor of that magazine. It provides first-hand experiences and important aspects of the Pacific war unfamiliar to an Australian audience.

My father’s parents met at some time during the First World War. Ian’s father was an Army captain in a machine gun unit in France and his mother was a NZ nurse on a hospital ship running between France and Britain. My father was born in Melbourne in 1922, however mother and son did not return to NZ until 1928 when he was of school age1.

Ian Pringle Speedy then followed the normal school pattern and he eventually left high school just at the outbreak of the World War II in Europe and took up a shepherd’s job in the King Country of the North Island. Even though his parents were more than well off, I think this was akin to our modern gap-year or the older notion of young gentlemen being jackeroos for a while.

Initial Training Wing

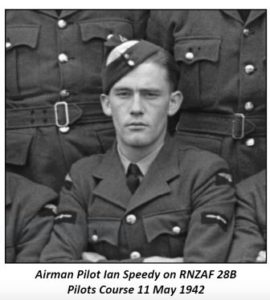

Ian Speedy enlisted into the RNZAF on 30 November 1941 at Levin’s Initial Training Wing (ITW), some 120 km north of Wellington. There were a number of ITWs in the country and like the others, this one was Ian’s introduction to the military: medical, uniform issue, drills, shooting and military law. It also covered principles of flight (but no flying), aero engines, armaments, basics of radio, photography, navigation, and aircraft and ship recognition. He joined Group V as Airman Pilot under training and stayed there for three months and for another month at ITW Rotorua.

Ian Speedy enlisted into the RNZAF on 30 November 1941 at Levin’s Initial Training Wing (ITW), some 120 km north of Wellington. There were a number of ITWs in the country and like the others, this one was Ian’s introduction to the military: medical, uniform issue, drills, shooting and military law. It also covered principles of flight (but no flying), aero engines, armaments, basics of radio, photography, navigation, and aircraft and ship recognition. He joined Group V as Airman Pilot under training and stayed there for three months and for another month at ITW Rotorua.

From Rotorua he went to Taieri near Dunedin and began his first flying at the No 1 Elementary Flying Training School. Here Ian did an eight-week course divided equally between learning to fly DH86 Tiger Moths (about 25 hours) and continuing his ground studies. Besides learning to fly, they were also trained in elementary map reading and pilot navigation. Successfully passing his elementary flying test, and with forty-two other hopefuls, Ian progressed to Service Flying Training School (Course 28B) in March 1942 for five months of more intensive flying training on Harvards. Next, he moved on to No 2 (Fighter) Operational Training Unit, Course 4, at Ohakea, (NW of Palmerston North) flying the aircraft he would eventually fly in combat – the Kittyhawk P-40E.2 He spent six weeks converting to the Kittyhawk before being posted to 17(F) SQN, first based at Seagrove SW of Auckland, until June 1943 then to another base north of Auckland in preparation for a ferry flight north to the Pacific Island, Espiritu Santo.

Ian left NZ and arrived in Espiritu Santo as a passenger in a C-47 on 2 August 1943. For the next six weeks, flying as wing man to each of the flight leaders, he practised the manoeuvres necessary in fighter combat. On 15 September he went with the squadron to Guadalcanal. On the first operational day, his CO, SQNLDR P.G.H. Newton walked home after bailing out of his aircraft.

A week later, three more P-40s were written off and another two badly damaged. Another Kiwi pilot in his enemy-damaged aircraft nursed his plane to another island, bailed out and spent a month waiting to be rescued. Four Japanese Zekes had been shot down in this period, although none by Ian.3

On 11 October, while wing man in a group of eight P-40s, Ian had his first taste of air-to-air combat in which three Zeros were shot down by others in his group. Ian’s CO SQNLDR Newton made one of those claims.4 In late October, Ian’s first tour was over and the squadron returned to NZ for a month’s leave. Squadrons were generally rotated on a six-week basis: six weeks in training at Espiritu Santo, six in forward combat areas then NZ for some leave. At Guadalcanal the RNZAF did fighter protection duties, getting a fair share of the action doing so. In June 1943, 15(F) claimed four Zekes, and 14(F) eleven, and another fifteen in July. American claims for June were 101 enemy aircraft of varying types against 31 confirmed by post-war research. With 16(F) in operations in August, they claimed six enemy aircraft and in September 17(F) claimed the four noted above.

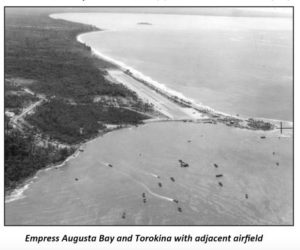

On 1 December 1943, in his own Kittyhawk with seven others and the company of the shepherding Hudsons, Ian flew from Auckland to Espiritu Santo for bomber escort, air-to-air firing, and ground attack practice. Two weeks later and with a new airfield at Torokina on the west of Bougainville on the beachhead5 separated only by dense jungle and a mountain ridge from another 38,000 Japanese, 17(F) SQN flew there via Guadalcanal. Rabaul was now only 200 miles to the north-west, 45 minutes away at cruise speed and plenty of fuel for combat while there. At Rabaul in its defence were 540 anti-aircraft guns and 200 aircraft at five airfields, an estimated 56,000 troops and another 5500 on nearby New Ireland.

Rabaul and its harbour full of ships had been bombed a number of times from high flying aircraft but with radar giving up to an hour’s warning, the Japanese were well prepared, fighters by the dozens already aloft and the bombs mostly ineffective. Lower-level bombing with greater fighter protection was the key that the base at Torokina now allowed. The first major raid on Rabaul with Kiwis from 16(F) and 14(F) was on 17 December. Sixteen P-40s took part and claimed six Japanese aircraft but with the loss of two of their number. My father was busy on other air attacks at Espiritu Santo that day, some 950 miles away to the south. There was to have been a follow-up raid on Rabaul on 18 December but bad weather prevented that. In a six-hour flight with other pilots in a C-47, Ian was flown north to Ondonga (Russell Island, 50 miles north west of Guadalcanal).

Very early on 19 December, twelve P-40s left Ondonga, flew north to Torokina to refuel and then with another dozen P-40s from 16(F)6 rendezvoused with 41 B-24 American bombers at 17,000 feet en route for Rabaul. The flak was heavy and the bombing seemed to have occurred without Japanese fighter interference but very quickly the Zekes were on the way. Only one was shot down, but with the loss of another two pilots in 16(F). Ian and his compatriots flew for over six hours that day.

Over the next twelve days, Ian flew a variety of eleven combat missions, strafing Japanese positions on the other side of the Torokina perimeter and another raid to Rabaul on 24 December where he claimed one Zeke confirmed and a second one damaged. The narrative from the post action report is as follows:

I saw a Zeke above me at 2 o’clock. Pulling up, I fired a long burst from 100 yards, closing up to 50 yards before ceasing fire. I saw my tracer going right into it and, as I pulled up over him, I saw the Zeke fall away sharply with smoke coming from the cockpit. As he steepened his dive, I saw him become enveloped in flames. As I did a climbing turn, I saw a Zeke diving on my tail. I broke away to the right, pulled out very fast at 4000’ and climbed straight up again to 6000’. I saw a Zeke in an easy climb crossing my path at the same altitude. Turning towards him, inside his turn, I opened fire at 150 yards and continued firing for three seconds as I followed him round. I saw my tracer going into him and he fell sharply away to the right and went into a spin. I did not see him smoke. As I went on my own, I came out at 1500’ fromBlanche Bay north east of St. George’s Channel. On looking behind me, I saw a P-40 dive straight into the sea approximately midway between Sulphur and Raluana Points.7 The P-40 was definitely not on fire and I did not see a parachute in the vicinity. I saw a Zeke make a crash landing on a reef. The aircraft did not appear to be badly damaged and I saw the pilot get out. I immediately opened fire and saw the pilot fall into the water, but could not observe damage to the aircraft.

Rudge (2003) then goes on to discuss the shooting of the Japanese airman and his aircraft on the reef. He notes that there was no extant policy except that destruction of the enemy on the ground as much as in the air was officially endorsed. But he then ends his argument about Ian citing the RAF, USAAF and Luftwaffe in Europe with ‘…there was a gentlemen’s agreement that pilots should not shoot at an airman in a parachute or dinghy. Having escaped a damaged aircraft…and survived it did not seem fair to be killed moments later.’ That may have been an idealisation of First World War aerial combat but it was not present in the total war of 1939–1945. Rudge himself (ibid, P83) describes six Zekes shooting at an Allied airman in a parachute on 7 June 1943.

Mr Rudge will have known about the tens of thousands of Allies killed in POW camps in the Pacific Theatre. He also was aware of the day-to-day experiences of all Allied pilots on the spot. They knew the unforgiving nature of warfare against the Japanese. In the European Theatre, war was being waged with a set of values not terribly different from the Pacific as A.C. Grayling describes at length in Among the Dead Cities; The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan. In Europe, the war was just as brutal as in the Pacific. The chivalrous kings of yore had left the battlefields and retired to their palaces at least two centuries ago leaving their minions to fight on their behalf while the kings watched on.

Following his conversion to the Douglas Corsair F‑4U back in NZ, a short time as an instructor and promotion to Warrant Officer, Ian then went back to Piva North, an airfield next to Torokina, on Bougainville Island. His tour with 22(F) SQN lasted from 24 April until 15 July, only a few weeks before the end of the war. In that time, he flew dozens of air-to-ground attacks. The Japanese air force had been destroyed but their army was still very active and fighting until the very last.

Ian had flown back to NZ with his squadron on 15 July and was demobilised on 8 August 1945. His combat flying was 260 hours in the P-40 Kittyhawk and 81 hours in the Corsair F-4U; all up over 340 hours in the thick of the Pacific War against the Japanese. In the ten months between May 1943 and February 1944, RNZAF fighter squadron pilots claimed 100 enemy aircraft destroyed and another 13 probables. At the same time, 21 Kiwi pilots lost their lives in this combat.

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on 3 August 1945. With the second atomic bomb on Nagasaki on 9 August, the Japanese surrendered on 15 August and the documents ratifying it were signed by the Japanese Foreign Minister on 2 September 1945 in Tokyo Bay.

Epilogue

I remember seeing my father in his RNZAF uniform just once. I was about five or six, it was 1949 or thereabouts so he was possibly at a reunion or similar as he had been demobbed since 1945. Not long after that we came to Australia as a family, living in and around Brisbane.

I joined the Royal Australian Navy in 1962 and made my career flying first as an Observer in our new Westland Wessex Mk31A anti-submarine helicopter and not long after, went on pilot’s course with the RAAF. Soon after getting my pilot’s wings I ended up in Vietnam as a member of the US Army’s 135th Assault Helicopter Company flying daily combat missions, getting shot at myself.

It was not until very recently that I really took an interest in what my father had done but I had nothing to go on. I remember his flying log book and numerous photos he had taken while on active service plus the certificates for his Zeke and the half share of another. But his log book and much of our family’s belongings were lost in a fire around 1963. The only original photo, and I still have it, is one of him at Espiritu Santo in his flying gear soon after he had arrived on his first tour with 17(F).

And then Rufus Anderson came along and saved the day – he and his father before him have done an amazing public service in collecting the stories of the WW II pilots of the RNZAF. Had it not been for their amazing efforts I would never have had what is the recreation of my father’s wartime flying log. The day-by-day detail is exceptional and I am most grateful for their work. Their narrative about him and those he fought with gives a clear story of just how tough it was in those perilous days when Japan seemed to be unstoppable.

Ian Pringle Speedy passed away quietly in November 2011 at the age of 89, not too troubled I hope by his wartime service. He would never speak about it.

References

These days, the internet seems to have something about everything and the references to the RNZAF, while sparse compared to the US in the Pacific, are still most valuable. Then there is the NZ Air Force Museum and their archives: the range, quality and clarity of their photos are brilliant. And David Homewood of ‘Wings Over New Zealand’ has been ever happy to find extra information for me.

My references to distances and so on across this vast area are only approximate. No good purpose would have been served to have been accurate in one system or another when talking about thousands of miles, statute or nautical. Google Earth was used as necessary.

Four books were my major sources:

Bryan Cox, Too Young to Die; the Story of a New Zealand fighter pilot in the Pacific War, Century Hutchison, 1987.

A.C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities; The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan, Walker & Co., 2006.

Alex Horn, Wings Over the Pacific, The RNZAF in the Pacific Air War, Random Century, 1992.

Chris Rudge, Air-To-Air, the Story behind the air-to-air combat claims of the RNZAF, Adventure Air, 2003.

Notes

- A very complicated story which I never got to the bottom of but full of intrigue!

- There were many models of the Kittyhawk, mostly to do with upgraded engines and weight reductions including gun combinations. By the end of 1944, over 13,700 had been built.

- The main shortcoming of the P-40s was poor ammunition quality causing many stoppages. The gunsight (Curtis Assembly 87-69-964) was an optical sight only that allowed the pilot to focus on the enemy and a gun bore dot – he still had to calculate aim off which was why high approach angles – beam and quarter attacks – were difficult so stern attacks were always preferred. It wasn’t until the Douglas Corsair F-4U entered service in late 1943 that gyro gunsights came into service and RNZAF 22(F) Corsair SQN may have had them. The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zeke/Zero turned far tighter than the P-40. The ‘Zero’ came from its association with the Imperial Japanese calendar, zero being the year 1940.

- I have used the word ‘claims’ rather than ‘kills’ as much of this detailed information has come from Chris Rudge’s accounts in Air-To-Air, the story behind the air-to-air combat claims of the RNZAF, where he corroborates the claims of the opposing sides with later research. Gun cameras were not available and different pilots could claim the same aircraft. With as many as 100 aircraft in a mêlée, it was easy to overestimate.

- The perimeter around Torokina at this time was about 8000 yards along the beach and 5000 inland. The airfield was 1500 yards long by 40 wide. Not at all secure as was proved many times.

- Six of these turned back for various reasons, leaving eighteen P-40s that went to Rabaul.

- These places are about five miles south east of Rabaul town, essentially in the middle of the harbour and enemy territory. Ian’s claims are for the two aerial encounters while the pilot and aircraft on the reef were not counted.