- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The remarkable story of Mrs. Ruby Boye has recently received considerable media attention. This version, dictated later in her life by Mrs. Boye to her friend and neighbour Mrs. Joy Wade, has not been published previously. It is with great pleasure that we have received this copy and family photographs from her grandson Mr. Philip Boye.

During and after the Second World War, newspapers of many countries published lengthy articles praising the courage of Ruby Boye, Coastwatcher and radio operator, who at great personal risk and under constant threat of death or capture by the Japanese, maintained a vital link between Vanikoro and Allied Intelligence posts throughout the Pacific during the Japanese occupation of the Solomon Islands.

In recognition of her bravery and devotion to duty, Ruby was awarded the British Empire Medal (BEM), the Pacific Star, the 1939-1943 Star, the 1939-1945 Medal and the Australian Service Medal.

There is an impressive collection of letters of gratitude and congratulation to Ruby, from many important sources. These include the citation and letters from the Department of Navy (Australia); Commander Long, Navy Intelligence; Australian Naval Liaison Officer, Vila (New Hebrides); Naval Liaison Officer (British Solomon Islands Protectorate); Colonial Office (10 Downing Street); Major General Vandegrift (US Marine Corps); the Christian Science Monitor (Massachusetts, USA); and Admiral Halsey, who also made a special detour from duty to offer his personal thanks and congratulations.

The investiture of the British Empire Medal was made by the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific in Suva in 1946. After the official ceremony, afternoon tea was served in the glorious gardens of Government House, where the Fiji Police Boys’ Band proudly added their talents in her honour, making this a memorable day.

Born in Sydney on 29th July, 1891, the fifth of eight children – three boys and five girls – (two of whom died in infancy), Ruby began life as Ruby Jones. Life in the Jones domicile was lively, happy and normal. A common bond, their love of music, strengthened family ties. Each child was taught to play an instrument of his or her choice. Ruby’s talent as a pianist and accompanist helped to create many happy musical evenings in an era when pleasures were simple and entertainments few.

As the young family grew to adulthood, some family members married. In the year 1919 Ruby married Skov Boye, a tall, handsome, blonde, Australian-born Dane who she had known for several years. Skov had visited the Solomon Islands in 1913 and had settled in Tulagi, returning to Sydney on leave every two years. At that time he was captain of one of Lever Brothers’ ships, recruiting natives to work on their coconut plantations throughout the Solomons group. After their marriage, the couple lived in Sydney for four years. A son, Ken, was born in 1922.

During the depression years, Skov returned to his former position with Lever Brothers. His wife and son joined him at Tulagi when Ken was 4½ years old. The family bought a lovely home and delighted in the island life, despite, over the years, occasional attacks of malaria and blackwater fever.

As recruiting trips throughout the Solomons were of several weeks Ruby was, at first, inclined to be nervous. She soon overcame this however, and learned to supervise the native house ‘boys’, the cook ‘boy’ and the garden ‘boy’. Much of her time was spent in the creation of a lovely flower garden and a small kitchen garden – a happy pastime for this energetic woman.

Tropical housekeeping

A steamer called every six weeks, bringing supplies of canned foods and fresh meat and vegetables, though the vegetables soon deteriorated in the tropics. The Boye family had their own chickens and ducks; fish (caught by the natives) was plentiful, and tropical fruit was bought from natives who called regularly from nearby islands.

The white population at Tulagi numbered about 40, most of whom were in some way connected with Government Headquarters. This small community spent much of their leisure time visiting or entertaining. The arrival of a ship, boat, or yacht meant open house to the friendly Boye family.

The family acquired several well-loved pets, including two cats, Ginger and Toby (an expert fisherman). An island parrot, which bore a resemblance to a parakeet, was Skov’s particular pet, and recognised only his owner. The bird was a great talker and a very clever mimic. Visitors were fascinated by his talents and Skov refused several offers to buy him.

Six months after her arrival on the island, Ruby returned to Sydney to await the birth of her second son, Don. She remained until the baby was 14 months old, then once again returned to Tulagi, leaving Ken, now six years old, with an aunt.

The children were subsequently educated in Sydney, though at one stage they spent 12 months with their parents, during which time their studies were continued by correspondence. Their parents were able to return to Sydney on leave every two years.

In 1936 Skov was offered the position as Island Manager of the Kauri Timber Company (of Melbourne) on Vanikoro, where the company held a contract to cut logs for transport to their timber mill in Melbourne. It was with some regret that they sold their home, leaving many good friends, to begin a new life and new duties 450 miles away, taking with them the two cats and the parrot.

The company provided a fine timber house. It was surrounded by wide verandahs and commanded a glorious, uninterrupted view of Vanikoro Harbour. Being built almost on the beach, it was on stilts. The family occasionally heard the nocturnal frolicking of crocodiles under the house.

The smallest island of the Santa Cruz group, Vanikoro is situated between the Solomons and the New Hebrides, its dimensions being about 10 miles long and three miles wide. A coral reef which surrounds the island about 1½ miles off shore is a hazard to shipping. There are only two entrances through the reef to the harbour, and ships are usually brought in by a pilot. It was at one of these entrances that La Perouse and his crew lost their lives. An iron cross (positioned on the reef and visible at low tide) marks the location of the shipwreck.

During the sojourn of the Boye family, Vanikoro’s only industry was timber. Logs were hauled from the Kauri plantations in the mountains by rail, tractors and other machinery, to the water, thence towed by launches to headquarters, rafted and floated, awaiting the arrival of chartered boats for loading and transport to the company’s mill in Melbourne (usually one boatload twice yearly).

About 80 native indentured labourers, who had been recruited from Malaita, New Hebrides, and other Santa Cruz islands, were employed by the company, under the supervision of white overseers. Apart from the Boye family, the white community averaged about twenty. The main buildings consisted of a Government Office, Government Residence, Post Office and houses for the company doctor, company manager, waterfront manager, radio operator (and radio station) engineers, native houses, and a couple of extra houses for the use of bushmen on weekend leave belonged to the timber company.

As canned and fresh foods were available only with the arrival of the timber ships, it was necessary for large quantities of canned foods to be kept in store. Fresh foods had of course to be used quickly to prevent deterioration. Butter, always canned, soon became rancid.

Bread was baked twice a week by native cook ‘boys’. To supplement the vegetable diet, hibiscus leaves were sometimes cooked and eaten as a substitute for greens, the flavour being similar to that of spinach. Green pawpaw, when cooked, resembled marrow. Fruit was plentiful and the selection varied, namely oranges, lemons, limes, mandarins, paw pow, mango, bananas, pineapples, coconuts, sour sops (of the custard apple family), also custard apples, and grenadillas, which were like huge passionfruit. On rare occasions, one of the beef cattle was killed, and the meat was shared by the white population.

Vanikoro’s rainfall was so great that it became automatic to reach for a raincoat and an umbrella before leaving the house. The Boye family soon adjusted to the new routine and the social life and made many friends, as they had in the various islands they had visited over the years. A number of these were to lose their lives later, during the war in the Pacific – some as Coastwatchers.

September 1939 saw the outbreak of the devastating Second World War. Within a year, at the age of eighteen Ken requested his parents’ permission to enlist in the RAAF. This was granted, and eventually, after training as ground staff, he was servicing planes at Goodenough Island and New Guinea. Young Don, aged thirteen, joined the civilian Air Observers Corps in Sydney, each in his own way contributing to the war effort.

The shattering news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7th December, 1941, cast its shadow on the peaceful lives of the islanders, as it did on the rest of the western world. In sadness and horror, they followed (through the medium of the teleradio) the progress of the war in the Pacific and, I am sure, prayed for the safety and deliverance of friends they had known. The company radio operator (who was employed for the purpose of communication and relaying weather information to the company’s head office in Melbourne) decided to enlist in the RAAF and arrangements were made for him to leave on a timber ship two days later. This, of course, meant that Vanikoro would be completely isolated from the mainland, without communication.

As the manager’s wife, Ruby felt it her duty to try to learn as much as possible about his work to fill the breach until another operator could be sent to take his place. To a novice, with only two days to learn so much, this proved to be an overwhelming and exhausting task.

Apart from the teleradio (which also had provision for morse code) the station was equipped with a complete range of meteorological instruments, whose intricacies needed to be understood in order to compile accurate weather information reports. After some instruction by the operator, Ruby spent those two days and one entire night practising and studying, with tenacious determination, and hoped that she would retain enough knowledge to carry on. As the weeks passed she became more proficient, and the tasks became routine.

Later, she studied morse code from lessons on short wave, as she found that her voice was sometimes distorted on the radio. The arrival of a qualified operator never eventuated. As Ruby was giving satisfactory service, the company was not permitted to send a replacement.

Detailed weather bulletins were broadcast four times daily, at regular intervals, and were of invaluable assistance to the allied air forces and navies, particularly to American aircraft operating in the area. Ruby was also able to pick up and relay messages from other stations when difficulties occurred. News of Japanese shipping and other activities was sometimes brought to her by natives, travelling from island to island by canoe. This information was also relayed, and was of great interest to the Allies. As the months passed, and the war expanded, Ruby was to provide a vital link with Allied Intelligence throughout the Pacific – at one stage (May 1942) relaying messages from the Coral Sea Battle to the American base at New Hebrides, when the Japanese were thwarted in their effort to take Port Moresby.

Immediate evacuation

At this time the fall of Tulagi was imminent, and a message was received from Headquarters, advising immediate evacuation of all Europeans from Vanikoro. A company ship, which fortunately was in the harbour at the time, was available, and arrangements were made for a hasty departure the following day. Disregarding their own safety, the gallant Boyes remained, knowing that they were separated, perhaps forever, from family and friends. Ruby had decided that as her schedules were of service to the Allies, she would continue as long as possible. Skov felt it his duty to protect the waterfront and timber company and to supervise the maintenance of the launches, punts, dinghies, tractors, and other machinery. The Government Official also remained, but left a short time later. With the departure of the doctor, Rubyassumed the responsibility of the welfare and health requirements of the natives. Those duties, combined with her broadcasting schedules, the compiling of weather reports, and the supervision of the home and food problems, left no leisure time for this indomitable woman.

After the evacuation all shipping ceased, and as the months went by food supplies gradually diminished. The island was now completely cut off from the outside world – no mail, newspapers or magazines. The teleradio was strictly for intelligence use only, except for personal messages to Ruby on three occasions advising her of family deaths. Between 1941 and 1942 she sustained the loss of her father, mother and a sister, all in Sydney. By mid-1942 the Japanese held Rabaul, Gasmata, Lae, the Admiralty Islands and Tulagi, and began to develop an air base at Guadalcanal. The decisive Battle of Midway gave the US sufficient strength to retake Tulagi and Guadalcanal by November 1942.

June 1943 saw the commencement of the offensive in the South Pacific and the South West Pacific. Enemy reconnaissance aircraft often flew over Vanikoro and occasional raids were made. On one occasion intermittent flashes of light were seen for about four hours in the vicinity of the reef, off Vanikoro Harbour, and boat engines were heard moving back and forth. It was believed that the Japanese were examining the entrances, but had decided that, as the hazards were too great, the island was of no strategic value.

Meanwhile, Japanese threats to Ruby, by radio, were becoming menacing, as they were aware of her broadcasting. On one occasion, following a broadcast to Tulagi, a Japanese voice was heard on the radio telling ‘Mrs. Ruby Boye get off Vanikoro pretty quick’. The ‘message’ was heard by Australian naval Coastwatchers who reported the incident to the navy.

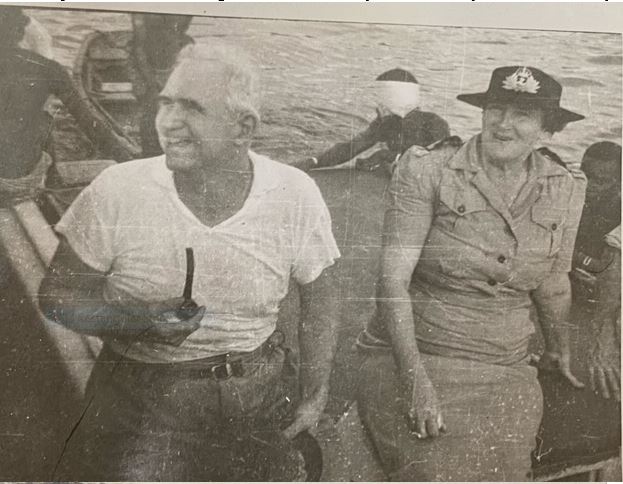

Lieutenant Commander Feldt received orders to proceed to Vanikoro to appoint Ruby as a Coastwatcher for the RAN with the honorary title of Third Officer in the WRANS. She was also accorded official recognition by the US as their ‘Third Army Outpost’. Both appointments were calculated for her protection in the event of capture by the enemy. In 1943 Ruby received a citation – she was awarded the British Empire Medal for devotion to duty. The actual investiture did not take place until 1946.

By 1944 the Americans had established a Catalina flying boat base at Vanikoro, and fuel tenders in the harbour refuelled aircraft which were operating over the Solomons during the offensive. Japanese reconnaissance aircraft still made occasional raids, the most serious being when an American tender was bombed and two American aircraft were hit. In return, four Japanese aircraft were shot down. The advent of the Americans meant a great improvement in the food situation, as they were able to replenish supplies. Books and magazines were made available for use of the islanders. It is doubtful that Ruby would have found much time for reading, however, as her duties had not lessened.

Occasional social visits by American officers made a welcome change for the Boyes. It was about this time, 1944, that Ruby developed shingles – a contributing factor, no doubt, being the stress of overwork during those years. Her condition was reported to Naval Headquarters by an American Captain. Although not seriously ill, NHQ decided that a complete change was necessary to effect a quick recovery. Hearing of her plight, Admiral Halsey wrote a fine letter to Ruby, congratulating her and thanking her for her devotion to duty, and suggesting that he would arrange air and sea transport back to Australia for her. Ruby was most grateful to accept. Soon after she had left, Admiral Halsey made a detour from duty to make sure she had got away safely, and to meet the husband of this ‘marvelous woman’ – unquote.

During Ruby’s three weeks’ leave of absence her post was manned by four Americans (radio operators and meteorologists). It was with great pleasure that, while in Sydney, Ruby was able to see all her relatives, and was delighted to be able to fly to Adelaide to visit Ken, who was stationed there at that time, studying a special RAAF course. The holiday, and, no doubt the relief from stress and strain, had indeed effected a cure of the shingles. Her health restored, she rejoined her husband at Vanikoro, and once again resumed her wartime duties which were to continue for many more months.

VE Day, 7th May, 1945, brought about the cessation of hostilities in Europe. Blessed news! Meanwhile an all-out offensive was being waged in the Pacific in a bid to end the war with Japan. As the enemy was driven further north the Americans withdrew from Vanikoro, but Ruby continued her schedules to the Allied Air Command at New Hebrides. Through a combined Allied effort on land, sea and in the air, the Japanese were being forced back on all fronts and eventually capitulated on VJ Day – 14th August, 1945. The joyous news was communicated to Ruby by teleradio and was then imparted in pidgin English to the natives, and Skov gave permission for celebrations. An enormous bonfire was built and enthusiastic rejoicing to the accompaniment of the crashing of tin cans continued for many hours.

After VJ Day, Government Officials and company employees gradually returned to the island and eventually production was resumed. Ruby was officially employed by the company as secretary to the manager and continued her weather schedules on behalf of the Meteorological Department in Melbourne. Life on the island gradually returned to normal as in pre-war times. It may be noted that Ruby received no payment for any of her wartime duties, which were entirely honorary.

The presentation of Ruby’s British Empire Medal was to have taken place in Sydney, but it was decided that as her wartime duties concerned the entire Pacific it should be held at Suva. As the appointment coincided with a well-earned holiday for the couple, they made a detour on their way to Australia, and it was at Suva that the ceremony took place in 1946.

In August 1947 Skov became ill, and acting on the advice of the company’s doctor he returned (with his wife) to Sydney for investigation and possible treatment. The illness was diagnosed as leukemia and within two weeks of his hospitalisation Ruby suffered another cruel blow – the death of her husband. Ken’s marriage to Miss Muriel Hoose took place two weeks later. Arrangements had been made some time previously and the family decided that a postponement would serve no purpose.

Accompanied by Don, Ruby made a final and sad return to Vanikoro where she resumed her duties for a period of three months while she trained a temporary manager and a radio operator before leaving for the last time the island where she had known happiness but also the nightmare of the war years. So great was their love of the islands that it is doubtful that Ruby would ever have left but for the untimely death of her husband. The pets were no longer there, all having eventually died of old age. At the termination of her employment Ruby received £1,000 retiring allowance from the company. This amount, and money saved, enabled her to buy a substantial modern brick home for herself and her son Don at Penshurst, in Sydney.

Both sons had chosen careers as draughtsmen, and although Don was still an apprentice at this time he insisted on assuming the role of breadwinner. His mother was able to supplement the budget by dressmaking and the sale of her exquisite hand-made tatted lace doylies, table mats, cuffs, collars, etc. She was accomplished at many types of handwork and needlework and was also an excellent cook.

As they settled to the new way of life, Ruby renewed acquaintanceship with several former island friends now living in Sydney. It became their custom, as it was at the time of writing (January 1970) to meet regularly at alternate homes. It was at the home of two of these friends, Alec and Ruth Glen, that Ruby met Mrs. Olive Price, and later, Mrs. Price’s father, Frank Jones, a tall stately gentleman many years Ruby’s senior. The friendship progressed, and in 1950 Mr Jones proposed to Ruby, who had never thought of remarriage. She was eventually persuaded and the marriage took place that same year.

A fondness and respect between Don and his stepfather contributed to a happy home life for the three. Unfortunately, soon after the marriage, Mr Jones’s health began to fail. His decline was gradual, over a period of several years, and Ruby nursed him through a prolonged illness until his death in 1960, which occurred soon after Don’s marriage to Miss Esme Thompson.

The bridal couple were by this time living in their own home at Caringbah. Now completely alone, Ruby faced life with the same courage and fortitude that had carried her through so many adversities.

During the latter part of Mr. Jones’s illness, Ruby was not well herself and required surgical attention, but she was unable to leave her husband. A short time after his passing, she was stricken by severe gall attacks and was eventually taken to hospital, where two operations were performed simultaneously. It was several weeks before she was restored to her former good health. In 1963 twin sons were born to Esme and Don, the surviving child was named Philip. Another son, Geoffrey, was born in 1969. I may add that Ruby is very proud of her grandchildren.

In the years that Ruby has lived alone, she has filled her life in many interesting ways. She has a vast number of friends with whom she corresponds, and sometimes travels to Melbourne, Geelong, Wagga Wagga, and once to Brisbane, to visit them. On occasion they return the visits. She is a member of the Red Cross and a women’s discussion group, and for years was a member of the VIEW Club. She takes an active interest in her garden and still finds time for her handwork, sewing, etc., and often minds other people’s children. At her present age of 78 years she has an alert mind and takes a keen interest in people and world affairs. She is blessed with a sunny nature and a sense of humour and has a very youthful outlook on life. My final tribute to Ruby Boye Jones is to say that she is a splendid neighbour and a very good friend, and it is my great pleasure to know her.

J.D.W.