- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Michael Wynd

In Australia we possess a plethora of material on Coastwatchers but know very little of a similar operation on the other side of the Tasman. This fine article by Michael Wynd, who is a researcher with the National Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy, is therefore particularly important to an overall appreciation of the Coastwatching organisation throughout the Pacific.

From the outbreak of the Second World War a Coastwatching system came into operation, organised by the New Zealand government and placed under the control of the Royal New Zealand Navy. From 1941 until the cessation of hostilities, New Zealand Coastwatchers maintained a lonely vigil on islands scattered over 26 million square kilometres of the Pacific Ocean, engaged in the most monotonous and unspectacular of all war service. Some 78 stations were established around the New Zealand coast, the South Pacific and sub-Antarctic islands. These stations reported to their parent stations on meteorological conditions and passing ships and aircraft. Important messages were passed to Auckland and to American naval authorities in Honolulu but the New Zealand naval authorities had overall responsibility for the scheme. New Zealanders would also serve as Coastwatchers with the Australian forces in the Solomons. The Coastwatching service in the Pacific is also one of tragedy. In October 1942 the Japanese committed a war crime when five civilians and seventeen Coastwatchers were murdered on Tarawa. By 1944 most of the Coastwatching stations were closed down or had become weather reporting stations and the last of the Coastwatchers would not return home until 1946.

New Zealand Coastwatching in the Pacific had its beginning with the establishment of a reporting network based in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands during the First World War which fell in abeyance in the postwar years. In 1929 the New Zealand Post and Telegraph Department (NZPTD) wrote to the Navy Office that radio stations set in the Cook Islands ‘would be to our advantage from the point of view of intelligence.’1 The New Zealand Naval Board (NZNB) created a plan in the same year for a War Watching Organisation that involved multiple radio stations collecting intelligence on the ‘position and movement of enemy forces’2 to be manned by naval volunteer reservists. The plans were revised in the late 1930s by the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy.

With the outbreak of the Second World War the Coastwatching system swung into action around the New Zealand coastline and it would take two years for the network of stations in the Pacific to come into service. It should be remembered that New Zealand’s Coastwatching stations ‘were mere pinpoints in the immensity of the Pacific Ocean.’3The area under New Zealand control stretched from Fanning Island, 368 km north of the equator, west to Makin or Butaritari Island in the Gilberts 2656 km west of Fanning. The southernmost station was located on the sub-Antarctic Campbell Island 5280 km due south of Makin. The other outlier was Pitcairn Island, 4624 km east-north-east from New Zealand. By March 1940 there were sixty-two stations, manned by service and civilian personnel, at different points round the coast, many of them in out-of-the-way positions.4

Although operational control was centred on the Navy, the Coastwatchers might be civilians or might belong to the three services; with this diversity the system functioned efficiently and the naval authorities were able to get rapid information of all shipping movements.5 For example the Coastwatching system organised throughout the Fijian and Tongan groups used local inhabitants to man scattered stations linked to the civilian communications by any means available.

By September 1940 the Staff Officer Intelligence in Wellington noted in a memorandum that the Coastwatching system instituted prior to the war breaking out ‘has proved moderately efficient.’6 The Naval Secretary sent a memorandum on 13 September 1940 to the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific:

‘The New Zealand Naval Board (NZNB) feel the most urgent necessity to ensure that the opportunity presented of obtaining early information of enemy movements is exploited to the full by Coast Watching and provision of quick and certain lines of communication. In this connection that Naval Board appreciate that the Gilbert Islands hold a position of special importance in the event of a Japanese sortie to the south from the Marshall Islands.’7

The Naval Secretary recommended installation of a number of radio sets and that personnel be recruited to operate them. These Coastwatching stations were approved in December 1940.

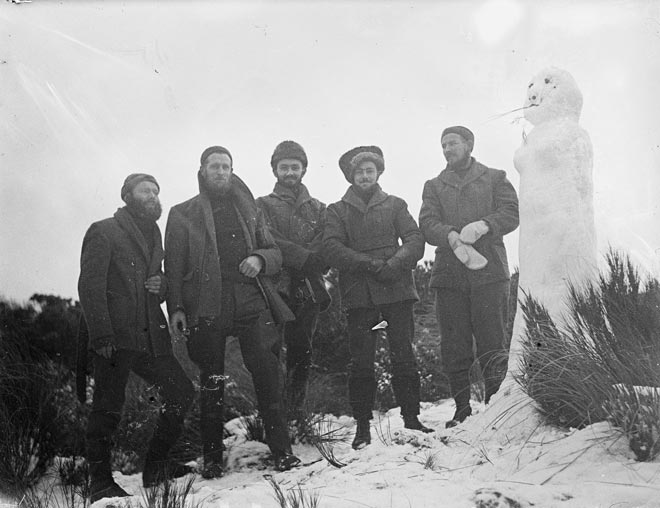

The other major development in December 1940 was the establishment of Coastwatching stations in the sub-Antarctic Islands. The War Cabinet decided that the uninhabited state of these southern islands was a threat to New Zealand’s security and that they should be occupied. For the purposes of secrecy, it was known as the Cape Expedition. Personnel and supplies sufficient for three years arrived in March 1941. The secret expedition only sighted two merchant ships in 1943 and by that time Wellington realised that these stations were far more valuable as meteorological stations which made critical contributions to forecasting the weather rather than sighting enemy shipping and aircraft. The Coastwatching parties were withdrawn in 1945.

Early in 1941 the NZNB initiated an extended service over the whole of the South Pacific. Coordination was established when a senior naval officer was appointed to Suva, and a senior manager of NZPTD was sent there by agreement with the Governor of Fiji as Controller of Pacific Communications, with direct control over the powerful Suva radio station and executive powers in an emergency.8 Following a discussion between the New Zealand government and Fiji it was agreed to locate a suitable control facility at Suva supporting a network of smaller radio stations in the various island groups.9 This was given the title Suva Aeradio. It was intended that the station would be used to coordinate all armed forces communication requirements throughout the Pacific area, including control of Coastwatching stations operated on behalf of the navy authorities in various island groups and to provide service links to New Zealand. This station was opened in early 1941.10 The Fiji government would use HMFS Viti and the schooner Degei for surface contact with stations established throughout the Gilbert and Ellice Groups.

Suva had a number of advantages as a control centre. It was geographically near the centre of the area and it was linked by cable to Australia and New Zealand, and via Fanning Island to Canada. A sighting report from an individual Coastwatching station would be immediately retransmitted to Suva by the more powerful parent station. Signals describing the sighting of aeroplanes or ships received at Suva from anywhere in the Coastwatching system were reported to the RNZN and if unidentified or important were retransmitted by Suva to Auckland.11

In 1941 the decision was made to assign the responsibility for establishing a Coastwatching network in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands to New Zealand. Plans developed by the New Zealand Chiefs of Staff were approved by the War Cabinet and the decision was made to give control to the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy. The Allies had attempted to obtain information about Japanese movements in the early part of the war without success. Due to the nature of the project it was undertaken in great secrecy.

It was determined that a trained radio operator with two soldier companions would be assigned to the stations and 22 volunteers from the Army were selected in April 1941.12 Each man was chosen ‘for their qualities of self-reliance and intelligence.’13 This system provided for a series of substations in each island group on which parent stations maintained a constant watch. These parent stations acted as clearing houses for the sub-stations and passed on to Wellington any vital information which came to them.14 The plan for the Gilbert and Ellice Islands was completed in May 1941 and put into operation in July. The operators were given training in weather reporting as this was just as important as sighting of enemy aircraft and vessels.15

Suva became the receiving station for a network which had as parent stations: Ocean Island, which watched ten sub-stations in the Gilbert Group; Funafuti, seven stations in the Ellice Group; Canton Island, four stations in the Phœnix Group; Fanning Island, three stations in the Line Group; Apia, five stations in the Samoan Group; Rarotonga, eleven stations in the Cook Group; Nukualofa, six stations in the Tongan Group; as well as nine stations throughout the Fiji Group itself. Wellington was the parent station for posts on Norfolk Island, the Kermadec and Chatham Islands, and Awarua (Southland) for the Auckland and Campbell Islands. In each island group a parent station passed on any messages received by it from individual Coastwatching stations and maintained a constant watch.16 There was a continuous link with the RNZAF station at Ohakea so that any immediate Coastwatching reports for the Navy Office Wellington could be sent.17 Coastwatching reports received at Suva were forwarded to the Navy Office in Wellington.

The Gilbert and Ellice Islands operation began in July 1941 when the equipment and stores prepared by the Army and the NZPTD was delivered to Fiji. Viti departed Suva on the 20th for a voyage of over 8000 km to establish the series of Coastwatching stations. Each party took nine months worth of supplies. Viti returned to Suva on 11 October 1941 and all stations were operational.

With the outbreak of the war in the Pacific the Coastwatchers remained on duty as ‘they had volunteered to remain at their posts, and the information they could give of the strength of an enemy attack and even the negative information that would be provided when they became silent were equally vital to the Allies.’18 Ocean Island was shelled by the Japanese on 8 December 1941. Panic broke out and the radio station was destroyed before the order was rescinded. Fortunately, the radio was able to be rebuilt using the equipment available on the island. On the 10th, 23 Japanese vessels arrived in the lagoon at Butaritari and the radio operator and his soldier companions were captured the next day but not before sending a distress signal and destroying the codebooks. They were the first New Zealanders to be captured by the Japanese. Little Makin and Abaiang were also captured. At Tarawa the radio was hidden and the Europeans placed on parole but the local official was asked by the RNZN to remain on air and keep up transmission of valuable intelligence. What followed for the rest of the Coastwatchers in the two island groups was months of tension as they continued to send in their weather and sighting reports.

The Coastwatching service operated very smoothly in the first months of 1942. With the movement of the United States Navy into the South Pacific in early 1942 it was arranged with Wellington that the naval intelligence unit in Honolulu would receive everything that was sent to New Zealand. Both stations also automatically retransmitted any signal received which had not originated with the other.19 Some Coastwatching stations were handed over entirely to the Americans. For example, American personnel manned two of the Tongan stations. The RNZN advised that a ship was being sent to resupply all the stations from Fiji not held by the Japanese and at the time the operators were asked if they wish to be relieved. In the Gilberts all chose to remain except one at Beru. In the Ellice Group all chose to stay. Resupply of the islands began in February 1942 when the vessel Degei took on cargo that had been shipped to Suva. Degei visited all the islands where it was thought safe and only went north as far as Nonouti. Supplies for Kuria, Abemama and Maiana were landed at Nonouti and were transferred to the other islands by launch or canoe, moving by night and sheltering in the lagoons by day. After calling at Beru, Degei returned to Suva on 18 March 1942. It had been a difficult voyage with the increased number of Japanese air patrols that covered the Gilberts which meant that Degei could only move at night and had to maintain strict radio silence. On the return of the ship it was reported that the morale of the Coastwatchers was still high.

September also marked the final occupation of the Gilberts by the Japanese. After bombing and strafing several of the stations, the Japanese sent in their surface craft with landing parties. Maiana sent a message to Beru on the 25th ‘Japanese coming – regards to all.’ Ocean Island made its final signals as it was being bombarded by Japanese ships and was captured on the 26th. Fortunately, the radio and codebooks were destroyed before capture. On the same day the Coastwatchers at Nonouti were captured and Japanese warships visited Beru. The two operators sent their final message: ‘Three enemy warships. Good luck’, before destroying their equipment and fleeing into the jungle, hoping to escape later. Because of Japanese threats of revenge on the local population they gave themselves up on 3 October. On the 28th Kuria advised that they were visited by two Japanese warships, went off air with the message ‘two warships visiting us now’ and the two New Zealanders were captured. Tarawa was taken and the temporary radio station that had been sending through valuable information was taken off the air. At the end of September Japanese forces had also visited Tamana and Nonouti.

NZ Defence Department

On 15 October 1942 the atoll of Tarawa was bombed and shelled by the United States Navy. One of the 22 Europeans held in captivity broke away and waved at the aircraft. For his actions he was shot and the rest of the prisoners were murdered that evening and their bodies dumped in a pit. A report on the fate of the captured Coastwatchers was only communicated to the New Zealand Prime Minister in December 1943 following the landings at Tarawa. A Court of Inquiry was held at Betio, Tarawa 16-20 October 1944 to ‘fully investigate the circumstances surrounding the reported killing of the seventeen New Zealand Coastwatchers and five other Europeans by the Japanese in 1942.’20 It confirmed the brutal execution of the New Zealand soldiers and civilians. The bodies were never recovered.21

In January 1943 NZNB recorded that it: ‘Has been particularly impressed by the calm, unflurried manner in which messages have been coded when the enemy had already landed on the island. The correct procedure for informing us when they were about to destroy their sets has been carried out up to the last minute. In every case, it is clear that they have kept going to the end, their one aim, regardless of their own safety, being to keep us informed. It may be relevant to stress here that a wireless set is an unpleasant thing with which to be caught in war.’

In April, five of the original operators in the Ellice Islands were relieved and returned to New Zealand. In October there was a ‘serious case of neglect of duty’ by an operator in the northern Ellice Islands.22 This was a critical time as GALVANIC, the amphibious operation to liberate the Gilbert Islands, was to begin in November with landings on Tarawa and Makin. The radio station had gone off air and just at the time when the Ellice Islands were to be the new front line in the Pacific campaign. The operator excused his performance by claiming illness and asked to be returned to New Zealand. It was considered by the authorities in Wellington as an ‘unfortunate occurrence’ for the reason that the Americans had ‘expressed the wish that the Coastwatching service should continue normally as any change in procedure or traffic would arouse the suspicion of the enemy.’23

With a reduction in the New Zealand intelligence effort the War Cabinet made a decision that of the 76 stations then in existence, many were to be abandoned, thirteen were reduced to care and maintenance basis and thirty were retained in full operation. Some stations were replaced by aerial patrols.24 Despite the closing down of most of the Coastwatching stations in 1944 the last of the New Zealand Coastwatchers did not return home until 1946.25

Both the RNZN and the United States forces based in Fiji expressed their commendation of the value of the work performed by the Coastwatchers in the Pacific area. The Coastwatching ‘proved well worthwhile’ and the stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands ‘had been a vital link in planning South Pacific strategy and war operations.’26

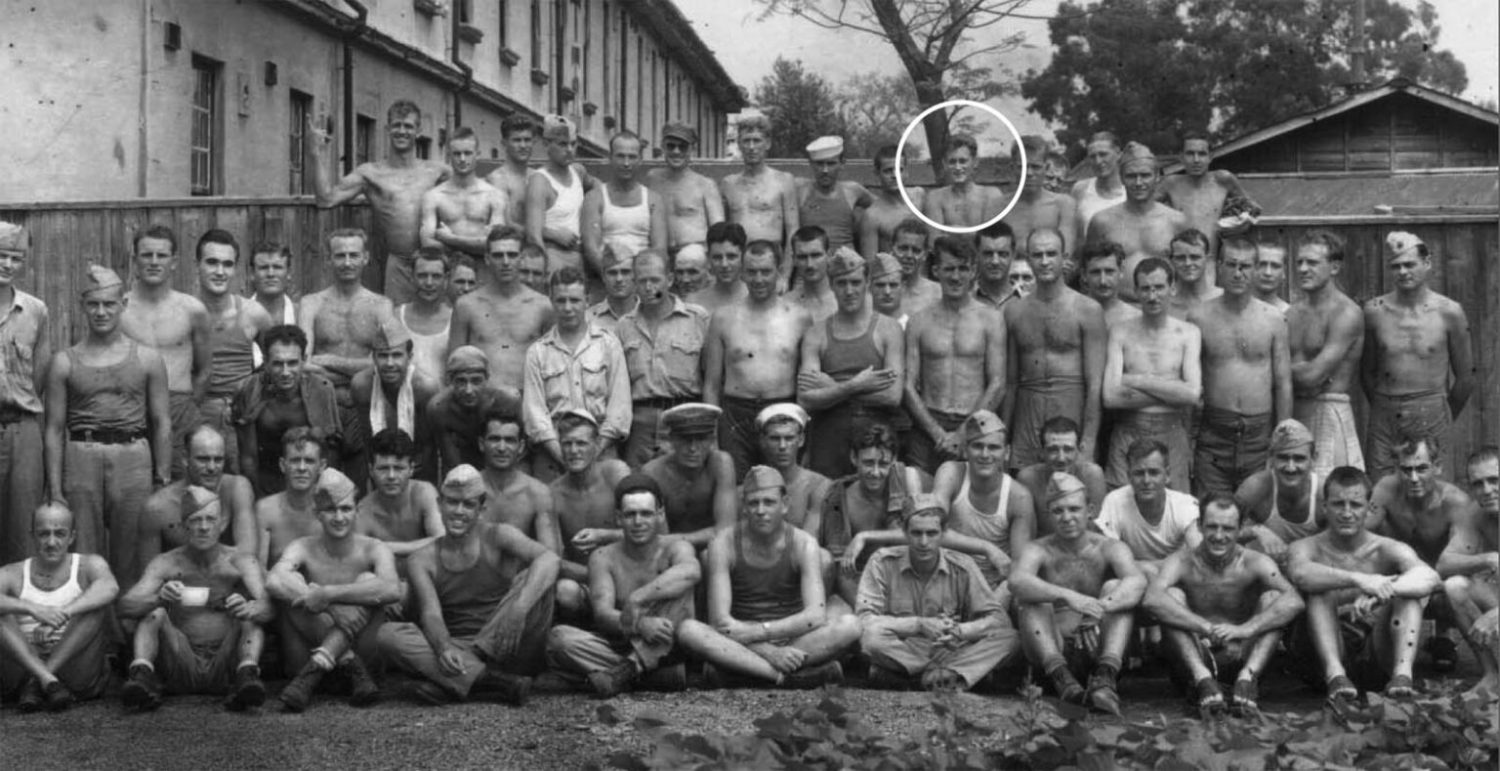

New Zealanders in Australian Coastwatching Operations

Although the Coastwatching service through the Solomons was organised by the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board, several New Zealanders were engaged there both before and after the Allied thrust when the islands were recaptured. Many of the administrative officials and planters joined this service. Eleven RNZN telegraphists were seconded to the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) to remedy a shortage of trained ratings. They operated at the parent radio station at Lunga Guadalcanal, at Rendova, and Munda from January 1943 to May 1944. Their reports were of the highest value to the Allied cause.27

In March 1944 the RAN recommended two New Zealand Telegraphists for gallantry awards for their service in the Solomons.28 Telegraphist George Carpenter was sent by canoe from Segi and joined a Coastwatching post on Rendova Island, in the New Georgia Group, before the American landing there. After the successful attack, remnants of the Japanese garrison retreated inland and accidentally hit upon the Coastwatchers’ post. The handful of Coastwatchers held off the Japanese for some hours but retired when the enemy brought up a machine gun. The signals staff had kept on sending messages under fire. As the Coastwatchers were leaving the post the Japanese rushed it, and Carpenter hurriedly destroyed the radio by wrenching out the crystals before he successfully escaped and was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.29 Acting Leading Telegraphist Niven Witham was attached to a Coastwatching party which went in with the United States Marines in November 1943 when they landed at Torokina, Bougainville. In action the principal duty of the Coastwatchers was to report aircraft sightings. Witham, who had erected new aerials while the post was being bombed, was also awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.30

In conclusion, the vast Coastwatching effort that New Zealand made in the Second World War would prove valuable even if it was providing negative intelligence. Both the RNZN and the United States forces based in Fiji expressed their commendation of the value of the work performed by the Coastwatchers in the Pacific area. The Coastwatching ‘proved well worthwhile’ and the stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands ‘had been a vital link in planning South Pacific strategy and war operations.’31

In his history of the naval intelligence organisation Sydney Waters wrote of the Coastwatching service: ‘The organisation proved its efficiency and value on innumerable occasions. It is fair to say that it was virtually impossible for a ship to show its masthead near one of the islands or the sound of an aircraft to be heard without C.O.I.C. knowing the fact within a few hours.’

He noted that those stations that didn’t report sightings provided what can be called ‘negative intelligence’ that is, ‘there can be much value in knowing where the enemy is not.’32 For many of the New Zealand Coastwatchers it was a lonely and mundane vigil and for some it was a task that led to their deaths. These men deserve to be remembered.

Notes:

1 Dale Williamson, For Special Duty Outside New Zealand: The New Zealand Coastwatching Service During WWII, Porirua: Privately Published, 2011, pp. 12-13.

2 ibid., p. 13.

3 Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1952, p. 229.

4 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 3.

5 ibid.

6 Dale Williamson, For Special Duty Outside New Zealand: The New Zealand Coastwatching Service During WWII, Porirua: Privately Published, 2011, p. 34.

7 ibid., pp. 90,190.

8 Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1952, p. 229.

9 Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, p. 1.

10 ibid.

11 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 6.

12 ibid., p. 7.

13 K.L. Sandford, The Story of the 34th, Oliver Arthur Gillespie (ed.), Wellington: Reed Publishing, 1947, p. 33.

14 Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1952, p. 230.

15 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 7.

16 Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1952, p. 230. See also Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, Part 1 p. 2.

17 Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, Part 7 p. 1.

18 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 25.

19 ibid., pp. 6-7.

20 Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, Part 25 p. 2.

21 ibid., Part 25 p. 6.

22 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 8.

23 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 8.

24 ibid., p. 3.

25 Ian McGibbon (ed.), The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History, Auckland: Oxford University Press, 2000, p.101.

26 Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, Part 27 p. 1.

27 D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 28.

28 Dale Williamson, For Special Duty Outside New Zealand: The New Zealand Coastwatching Service During WWII, Porirua: Privately Published, 2011, pp. 141-142.

29 Oliver A. Gillespie, The Pacific: The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, Wellington, Historical Publications Branch, 1952, p. 238.

30 ibid. See also Eric Feldt, the Coast Watchers, Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1946, p. 302 and D.O.W. Hall, Coastwatchers, Wellington: War History Branch Department of Internal Affairs, 1951, p. 30.

31 Donald Vaughan, Report on Coastwatching Radio Stations in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands 1941-45 (New ed.), Raumati South: Privately Published, 1997, Part 27 p. 1.

32 Dale Williamson, For Special Duty Outside New Zealand: The New Zealand Coastwatching Service During WWII, Porirua: Privately Published, 2011, p. 19.