- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW2, Influential People

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

That fine old Aussie expression ‘I don’t know you from a bar of soap’ has now fallen out of favour as we move from the utilitarian bar of soap to liquids found in plastic containers. But the humble bar of soap was not only important to our hygiene but was instrumental in the development of our historical past.

The origins of soap making are obscure but soap was around in Roman times as they liked a bath; it was made from a mixture of oil and ashes, and the word ‘soap’ is taken from the Latin ‘sapo’. As the product was refined and gained popularity Good Queen Bess (Elizabeth I) reportedly took a bath once a month ‘whether she needed it or not’. But most of her loyal subjects didn’t bathe or even wash their hands.

During the 19th century the likes of Louis Pasteur understood that good personal hygiene reduced the spread of diseases, and the idea of cleanliness started to be embraced, especially by the new prosperous middle class.

Lever Brothers

Two brothers from the northwest of England, James1 and William Lever, inherited a wholesale grocery business from their father. In 1885, in partnership with William Watson, a local industrial chemist, they invested in a small soap works. Watson invented a new soap making process using glycerine and vegetable oils, rather than the traditional tallow from animal fats, to produce a freely lathering soap which became an instant success. ‘Sunlight Soap’ had arrived, with the Lever brothers patenting the product. This was given a further boost by clever marketing. Bars of soap were individually covered in attractive heavily advertised wrapping – save 40 wrappers to receive a free copy of a detective novel by bestselling author Arthur Conan Doyle.

With increased production new premises were built on marshlands near the banks of the River Mersey, opposite Liverpool, in what became known as Port Sunlight. Here could be found all manner of trades including cooperage making barrels and sturdy wooden crates, or soap boxes, the universally free storage containers and impromptu stages of orators.

Lever Brothers entered the US market in 1895, quickly becoming a major supplier of soap products to the American market. The company continued to expand through acquisitions including A&F Pears, makers of a famous brand of translucent soap. In 1906 Levers acquired Vinolia, an exclusive manufacturer of perfumes and high-grade soaps. Vinolia was the only soap selected for first-class passengers on board RMS Titanic. In 1922 they acquired the large wholesale meat supply business of Thomas Wall and through this branched out into frozen foods, ice-cream and fish products (Mac Fisheries).

Australia and the Pacific

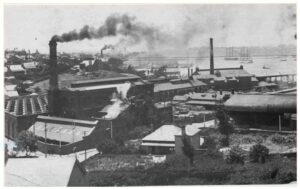

Lever Brothers entered the Australian market in 1897 when they opened a factory in the Sydney suburb of Balmain to extract the oil from copra brought from the Pacific islands. Initially this was shipped back to Britain. By 1900 the factory produced glycerine and its first bar of Sunlight Soap at Balmain. At its peak in 1958 the Balmain factory employed 1250 workers.

In the early 1900s the company sought to secure production and supply of its base product, palm oil, through control of plantations in the Pacific Islands and the Belgium Congo. Lever Pacific Plantations was incorporated in 1902 to gain control of raw materials like copra, phosphate and timber. Levers acquired leases over property in Fiji, New Guinea, the Solomons and other Pacific islands. By 1925 they had numerous estates in the islands which were mainly managed by Australians, reporting to the Sydney based general manager George Fulton. In addition, smaller plantations supplied their products to Levers with the main receiving and distribution base for copra being at Tulagi in the Solomons, from where Levers operated its own steamships.

In 1914 Levers acquired a majority shareholding in Australia’s largest soap manufacturing company, the Melbourne based J. Kitchen & Sons. In September 1929 an agreement was signed which created what The Economist described as one of the biggest industrial amalgamations in European history, with the merger of the Margarine Union and Lever Brothers. The main reason for the merger was to reduce competition for raw materials of animal and vegetable oils used in the manufacture of margarine and soap. The merged Dutch ‘Margarine Unie’ and Lever Brothers formed Unilever, one of the first multinational corporations with 250,000 employees.

Another Englishman, William Colgate, started a soap and candle making business in New York in 1806. This expanded and grew into the mighty Colgate-Palmolive company which also opened a factory in Balmain in 1923. In 1993 the value of Sydney real estate resulted in the building being replaced with high-rise apartment living complexes.

Employee Welfare

Lever Bros took a paternal interest in the welfare of its British based employees with progressive working conditions including an eight-hour day, holidays and sick leave.

A model village was built next to its main manufacturing plant at Port Sunlight. This was based on the ‘Garden City Movement’ with fine quality housing in various architectural styles. Over 800 houses with a population of about 3500 were set in landscaped grounds complete with a church, school, shops, a pub, boat pond, war memorial, museum and a first-rate art gallery.

The Lever family saw this as a profit-sharing venture returning profits directly to the benefit of contented employees providing decent housing with proper sanitation. In today’s world where colonialism is questioned as a racist and discriminatory period of history it could be argued that those in Britain benefitted to the disadvantage of fellow workers producing raw materials in Africa and the Pacific. Although by the standards of those times, those producing raw materials also benefitted from training, educational and medical assistance.

William Hesketh Lever grew up in the working class Lancashire town of Bolton. He attended a local private school with a near neighbour Elizabeth Ellen Hulme, the daughter of a draper who lived over his shop. In 1874, Elizabeth aged 23, married William, one year her junior, and they set up home in a terraced house.

In later life Elizabeth and William were extremely well travelled visiting Europe, America, Africa and Australia. They assembled a valuable collection of art works and antiques at their home at Thornton Hough about four miles from Port Sunlight. William and Elizabeth first visited Australia in 1892 and as Sir William he last visited Australia in 1914 as part of a worldwide tour of Lever interests. When Elizabeth died in 1913 her husband was Sir William Lever, so she became Lady Lever but never Leverhulme. It was not until 1917 that Sir William was elevated to the peerage and took the title Lord Leverhulme. Inspired by his wife, the Lady Lever Art Gallery at Port Sunlight was built in her memory, and contains much of their treasured collection taken from their manor house at Thornton Hough.

One of the many fine pieces on display at the Lady Lever Gallery includes a portrait of Lady Emma Hamilton painted in Naples by the French artist Vigée Le Brun. As Emma Hart she had been born in a village near Port Sunlight where her father was a blacksmith.

Wartime Contribution

Soap and its byproducts are not only used as an important cleaning agent but also as additives in the food, explosives, medical and pharmaceutical industries. Unilever had to overcome immense difficulties during the Second World War with Allied blockades reducing supplies to its Dutch factories and challenging its important German markets. But throughout both world wars soap was provided not only to the general public but to troops in the field and ships at sea. And glycerine was used as a chemical agent in the manufacture of deadly explosives.

In the Pacific War in isolated regions large plantations were often central hubs of communities with housing, storerooms, factory facilities, and wharves. These were requisitioned by Allies and enemy alike as temporary headquarters and the trees often felled to make aircraft runways. Levers lost most of its Pacific islands’ plantations during WWII and many of its employees became victims in the conflict.

Future Development

Business at the large Unilever industrial complex at Balmain was wound down in the 1970s and production ceased in 1988 when the site was turned over to high-rise apartment living complexes. Thousands of jobs have been lost with the business now scattered to smaller satellite enterprises in the outer suburbs. The Port Sunlight facilities which once contained five factories finally ceased production in 2021 when the last 125 workers were redeployed. The model village with its museum and art gallery is retained as a monument to Lever Brothers and the soap making industry.

Traditional soap making has moved on from tallow and vegetable oils to synthetic manmade materials as it develops new markets in liquid forms and as detergents. The large factories employing thousands of workers are no more, being replaced by automated chemical plants and distribution centres. An industry now largely carried out in chemical laboratories and marketing campaigns.

Notes

James Darcy Lever was the second son of James Lever (senior) but did not take a major part in running the business. In 1895 he fell ill, possibly due to diabetes and resigned his directorship. He died at the family home at Thornton Hough in 1910.

References

Nash, Jim, Unilever – History, from presentation August 2014, available online.

Moore, Clive, Tulagi Pacific Outpost of British Empire, ANU Press, 2019.

Racism, the Belgian Congo & William Lever, Port Sunlight Village Trust, June 2022.

Formation of Unilever, Information Guide No 4, Unilever Archives, Port Sunlight, undated.