- Author

- Book reviewer

- Subjects

- History - WW2, Book reviews

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

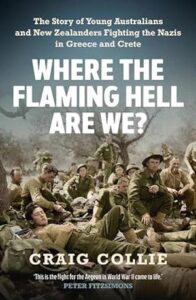

Where the Flaming Hell are we? This new wartime history by Craig Collie paints a vivid picture of Australian and New Zealanders desperately fighting in Greece and Crete and as the title describes, few had much idea of where they were or what they were doing there. Published by Allan & Unwin, Sydney, of 372 pages, with a liberal supply of photographs and maps. Available at all good booksellers at about $25.00

Where the Flaming Hell are we? This new wartime history by Craig Collie paints a vivid picture of Australian and New Zealanders desperately fighting in Greece and Crete and as the title describes, few had much idea of where they were or what they were doing there. Published by Allan & Unwin, Sydney, of 372 pages, with a liberal supply of photographs and maps. Available at all good booksellers at about $25.00

The North African campaign with its Rats of Tobruk and sea battles of the eastern Mediterranean epitomised by the Scrap Iron Flotilla are well known histories written by victors but defeat in the Greek campaign largely fought by Anzacs is all but forgotten.

When Italy joined the Axis in June 1940 Mussolini was intent on regaining the glories of a past Roman Empire by extending Italian influence through southern Europe into North Africa. Accordingly, his troops advanced into British controlled Egypt threatening the strategic Suez Canal. In addition, Greece was being pressured into providing concessions to Italians advancing through neighbouring Albania.

In response the 4th Indian Division supported by the British 7th Armoured Division drove the Italians back in Egypt claiming a significant victory. The Indians were relieved by the Australian 6th Division, and later joined by the 2nd New Zealand Division, again with British armour claiming another resounding victory against dispirited Italians. With supply lines stretched the advance against the Italians halted.

As the war in Africa was going well the British Government, in a Churchillian political gambol aimed at encouraging the Balkan states and Turkey to join the Allied cause, sought to divert resources and provide assistance to Greece. At this stage Germany, planning a Russian invasion, wanted to maintain the status quo in southern Europe. On the other hand Britain provided bombers based in Greece and inserted a garrison and naval refuelling facility on Crete, thereby allowing a Greek division to relocate from Crete to bolster forces on the mainland. Germany saw this as a threat, especially to its vital Rumanian oil fields.

The Italians were now stopped in North Africa, and in Greece, they were hampered by severe weather in rugged mountains and driven back by defiant Greeks. In April 1940 the war of the titans began with over 60,000 British and Commonwealth forces (mainly Australians and New Zealanders) with their supplies being shipped from Egypt to Greece. Germany responded too, with its Afrika Corps ordered to Libya and its 12th Army into Greece.

The ensuing clash in northern Greece was a big awakening to Commonwealth forces now facing a formidable enemy with deadly air superiority. Integration between Anzacs and rugged Greek forces who knew the country was less than desirable with troops trained for desert warfare finding conditions in cold and inhospitable snow-capped mountains traversed by goat tracks extremely difficult. As a result, the Allies were soon in retreat to a new front which was again hammered by constant air attacks with virtually no RAF counter support. When German armour joined the fray the Allies were again in retreat and were soon retracing their steps to Athens and planning an evacuation. The war on mainland Greece only lasted three weeks with surprisingly few casualties but about 10,000 became POWs. With an amazing naval effort 50,000 were evacuated over five consecutive nights in scenes reminiscent of Anzacs at Gallipoli.

Most evacuees, leaving much of their arms and supplies behind, found themselves in Crete where they regrouped and joining the small garrison as ‘Creforce’ eventually under the command of New Zealand’s Major General Freyberg. Freyberg, a hero of the Great War with a DSO and two bars plus a VC, had married into English society and was known to Winston Churchill who may have influenced his appointment.

The numbers available to Creforce can be confusing. The original British garrison comprised 5300 troops plus RAF personnel, totalling say 7000. Reinforcements mainly came from 2000 Royal Marines and those evacuated from Greece, say 23,000. In addition, there were about 10,000 Greeks, including local militia and police. The impressive grand total was about 42,000 but of these little more than half were trained and armed combat troops; there were many support elements, artillery without guns, armoured corps without armour, and poorly equipped local forces.

The Allies were defending the north coast with Freyberg and his headquarters in the centre in the ancient capital at Chania and not far distant from the Royal Marines at Suda Bay, the New Zealanders west at Meleme; to the east the Australians were at Rethymnon and furthest east the original garrison in the largest city Heraklion.

Against this the Axis pitted 16,000 German and 2700 Italian airborne troops with a further 7000 seaborne being scattered by the Royal Navy and failing to arrive. The defenders therefore had an advantage of over two to one which on paper should have made the German planned invasion hopeless. So what went wrong?

The author has conducted an enormous amount of research in providing an excellent narrative which intermingles official histories with personal records taken not only from senior officers but also those from other ranks. This helps provide a skilfully told history of desperate actions both in Greece and Crete resulting in disastrous defeats and evacuations with many taken prisoner. Possibly one of the finest accounts of Anzacs in action in the Mediterranean theatre during the Second World War and comes very highly recommended.