- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Dr. Richmond Jeremy,

OBE MB ChM FRCP FRACP 1899 – 1995

Notes made by Dr. Jeremy were transcribed and published in 1998 by his son Richmond Jeremy. With permission of the Jeremy family these have been further condensed and divided into three parts.

Richmond Jeremy was born in Wagga Wagga, New South Wales on 7 August 1899 the son of a stock and station agent, John Jeremy. He was educated at Sydney Church of England Grammar School, before studying medicine at the University of Sydney. He represented his school in rugby and rowing and attained the rank of Lieutenant in the Cadet Corps. Continuing rugby at university he gained his Blue, and graduated Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery in 1923. He then joined Sydney Hospital as a resident medical officer and in 1926 was off to London for further training, leading to membership of the Royal College of Physicians.

On return he entered general practice in Rushcutters Bay, where he purchased a house. Marriage came in 1929 to Joan Marjorie Wedgwood and they had three sons, Richmond, David and John. In 1936, after visiting a number of medical centres in the USA and Canada he established a consultancy in Macquarie Street, specialising in haematology and cardiology.

Early in WWII Dr. Jeremy volunteered for military service and was appointed to the Army from 4 July 1940 as a Major, at nearly 41 years of age. He left Australia on 28 December 1940 as part of the 6th Division of the Second AIF for service in the Middle East. He returned to Australia on 28 August 1941 and was later discharged medically unfit but after Japan entered the war he served again part time at the 113th AGH at Concord, Sydney.

Summary of the History of the 2/6th Australian General Hospital (AGH)

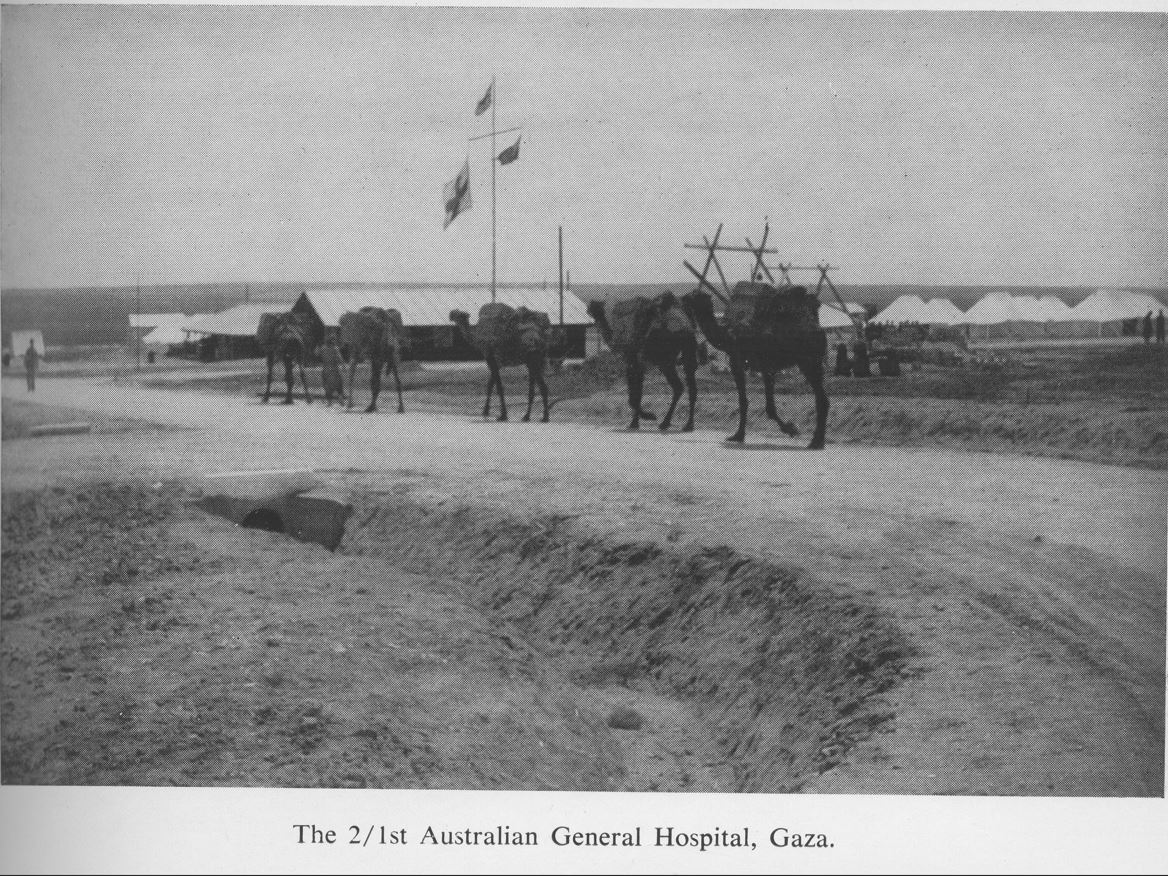

The 2/6th AGH was formed on 22 July 1940 at the Sydney Showgrounds with four officers and 33 other ranks and relocated to Wallgrove (Eastern Creek) Army Base to take over running a 600 bed camp hospital. However, on Christmas Day 1940 they returned to Sydney and boarded HMT Queen Mary. Three days later Queen Mary departed with Aquitania, Awatea, and Dominion Monarch, later joined by Mauretania and Manunda. The convoy departed Fremantle on 5 January 1941 with Queen Mary later proceeding independently to Trincomalee, where troops and hospital staff transhipped into five other ships. On arrival in the Middle East the troops disembarked for training in Palestine and the 2/1st AGH hospital staff was established at Gaza.

The 6th Division later moved to Egypt to bolster the defence of Alexandria and the 2/2nd AGH hospital was established at Kantara on the banks of the Suez Canal. The 6th Division then joined British forces fighting against the Italians who had invaded Libya. The Allied force performed well, advancing as far as Tobruk and taking many thousands of prisoners.

In late February 1941 advances against the Italians ceased and troops were withdrawn to Egypt in preparation to assist Greeks who were resisting an Italian invasion. Medical concerns were held as large areas of Greece suffered from malaria which had caused heavy casualties during the 1914-18 war. As part of these plans an Australian hospital was to be established in Athens and another at an advanced base near Volos in central Greece.

When the ill-fated Greek affair was about to start, the 2/6th AGH together with the 2/3rd Casualty Clearing Station moved to Alexandria, boarding HMS Orion, a cruiser of the Third Cruiser Squadron, which sailed on 7 March 1941 for Piraeus, arriving there the next day. Nursing staff followed later in HMT Pennland. Tasked with setting up a forward hospital at Volos, problems were experienced with non-delivery of equipment. Before establishing a fully functional hospital they were evacuated to Crete on 27 April 1941. From Crete, they sailed in HMT Nieuw Zeeland to Alexandria, and then travelled by train back to Gaza.

The 2/6th AGH with other hospital staff then re-established itself at Gaza, remaining there from May 1941 until February 1942. Next stop was Jerusalem where they utilised the ‘Kaisers Palace’1 on Mount Scopus before returning to Gaza from March 1942. When Australian forces departed the Middle East to defend the homeland against Japanese attacks on 1 January 1943 hospital personnel boarded HMT Queen of Bermuda for Fremantle where they arrived on 12 February 1943. On 19 February 1943 they completed the circle when boarding Queen Mary in Fremantle for Sydney.

From Sydney to Palestine

I was placed in charge of the ‘hospital’ in Queen Mary on the voyage from Sydney to Trincomalee in Ceylon. I recall that Dr Victor Coppleson removed an acute appendix and an epidemic of measles was encountered. The movement of the ship was very slight, but in spite of this Charles Lawes and Sister Crittenden were seasick. The trans-Tasman liner Awatea, in line astern, pitched and rolled violently, but Queen Mary was only slightly affected.

At Trincomalee the troops were transferred to smaller vessels, so I was charged with moving the patients. Our men did the stretcher bearing, very heavy work when I tried it. When the disembarking was concluded Rex Money told me a patient from the hospital had been lost, and it was my responsibility for this Court Martial offence.

Our unit, the 2/6th AGH, transferred to Dilwarra, a British India transport. On reaching Colombo I transferred to lndrapoera, a Dutch vessel with the 2/15th Battalion, a Queensland unit which had been in Darwin. Here I assisted the battalion MO, Ronald Hoy. Indrapoera was a small liner with narrow corridors and compressed sewage pipes which often became blocked. There was pneumonia and measles among the troops and I recall four young men in the ship’s ‘hospital’, which was a cabin in the fo’csle except for the label ‘Hospital’ over the door. The very good-looking Sister Parke came down to sponge these men. There was a good wine cellar, and Liebfraumilch and Bols gin were cheap.

My first attack of renal colic occurred on this ship; when telling Ron Hoy of my symptoms he said ‘I hope it is not a staghorn job requiring major surgery’. I was passing ‘gravel’ – crystals of sodium oxylate, but fortunately, this soon stopped. An officer came to Hoy to tell him that some of the men had bought ‘Spanish Fly’ which had a reputation as a potent aphrodisiac; the officer asked what he should do and Hoy said ‘put some barbed wire around the nurses’.

We were held up in the Bitter Lakes where the Germans had laid acoustic and magnetic mines from the air. Wellington bombers with large round loops of wire underneath to produce a magnetic field were used to explode the mines. In a trial to counter acoustic mines a motor boat was fitted with a support in front of the launch, which helped explode the mines but also destroyed the launch. While in the Lakes we went by boat to another ship to see some pneumonia cases. Charles Lawes was on this ship as was the man ‘lost’ at Trincomalee when disembarking from Queen Mary, he had decided to join a friend in another unit, so no court-martial.

We finally left the ship at Kantara with the 2/15th Battalion which was to go on to Kilo 89, alongside the 2/1st Australian General Hospital. I got off at Gaza with my gear but there was no-one there. It was not long before an officer came along in a car who told me of the risk as natives would murder for loot and used to stretch wire across the roads to get our despatch riders on their motor-bikes.

Palestine and the 2/1st AGH

The first Australian Army hospital established overseas in WWII was the 2/1st AGH at Gaza. Here most of 2/6 AGH were billeted and where my friend Lorimer Dods greeted me.

It was rough harsh country but when we got there some sleeping huts had been built. We were put up in EPIP tents – ‘European Personnel Indian Pattern’; they were spacious and comfortable. When Italy entered the war in June 1940 blackouts were imposed in Palestine. The proliferation of ditches and trenches and building materials around the hospital resulted in numerous injuries due to falls in these obstacles.

We had one batman between us, Sid Glaister. When I arrived Major Barton of the 2/15th Battalion was astonished, a Major without a batman! An indication that we were not regarded as true Majors. Captain Hoy had a batman who laid out his uniform for him, and smelt his socks to see if they needed changing.

Gaza, beach and town, was about two miles away. As far as I could tell, racially and politically the country was quiet, although there was some local unrest. Photos could be developed and printed in town, one of the sisters showed me some photos she had taken of our convoy! This lack of security probably did not matter. One day Stuart Marshall and I went to Jerusalem. On the way we tried out my revolver on a tin can, a lot of noise but the tin remained untouched. The revolver was one of those issued to all Australian Army Officers prior to departure overseas.

We went to a rather depressing leave centre, then down the Via Dolorosa to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with booths for various religions, who all had the piece of the Cross. Outside it was the Crusader grave with its effigy, as in the Temple Church in London; nearby was the Wailing Wall which was in use. Arthur Kennedy was sent to inspect a brothel at Jaffa, the Arab and southern part of Tel Aviv. He was not pleased about it, but the army liked to do this to you, to put a newcomer in his place. Ewan Murray Will who wanted to do dermatology was at first used to inspect latrines.

We were in Palestine not long after the successful Battle of Bardia. Rod Macdonald, who had been a battalion medical officer, gave a talk on his experiences. In one camp there was a large collection of officers’ uniforms, in gay colours, taken from the many Italian prisoners. After this battle we attended some of the wounded. There was bacillary dysentery, and sulphaguanidine was not available for its treatment; undoubtedly there was amoebic dysentery. There was meningococcal infection in the camps and Lorimer Dods had a special tented ward which was a most impressive place, three EPIP tents were ‘brigaded’ together; matting covered the dirt floor with smart army nurses in attendance. Sulphapryidine was given by mouth or by stomach tube to an unconscious patient; the results were excellent. It was an example of how volunteers were skilfully treated by caring volunteers. The faeces of bacillary dysentery were sterilised in 44 gallon drums heated by the curious oil and water fires used in the army.

After the battles in Syria, one night de Burgh watched the malarial casualties streaming into the hospital; they looked well enough but they would have been treated before being sent down the line. Our army did not anticipate the amount of malaria that ensued. At night planes would pass over the hospital on their way south but there were no attacks. I had renal colic and a large dose of morphine and was content to lie snug under the blankets on my bunk in the tent; on two later occasions I was admitted to hospital. Before our unit left for Greece there was some doubt about whether I should go, and Dods wanted to take my place. We envied him having patients to care for and he deserved to have these duties because of his early enlistment. Shortly after, a man was admitted to hospital with one leg blown off, but he survived. He had been tinkering with a live Italian aerial bomb which exploded in his tent. It was extraordinary how men would tinker with live ammunition. It was said that Arabs were prone to do this with unexploded shells, sometimes quite large ones.

There was a cinema theatre in the grounds to which I went once. The Palestine Post was delivered in the mornings by small Arab boys. We occasionally saw smart Palestine Police, mainly Englishmen. There was a small garden around the Officer’s Mess which Jim McCulloch watered with a hose.

Prior to our departure for Greece I was sent with Eric Hughes-Jones, a Melbourne surgeon, to do some Medical Boarding at the 1st Australian Convalescent Depot at Kafr Vitkin near Nathanya, south of Haifa. Mount Hermon, on the Golan Heights, was easily seen from our depot, beyond which are the plains of Armageddon. Medical Boarding was new to me but Eric taught me, he was very thorough. We worked in a tent and Major Maitland went to great trouble to herd two donkeys up to the tent and alongside the notice ‘Medical Board’.

On the way up to Kafr Vitkin we stopped for tea at Tel Aviv which seemed a dreary new seaside town; we saw some Polish officers in their tricorn caps. One night we went to nearby Nathanya for an orchestral concert by the Palestine Orchestra. The Colonel was paying much attention to an attractive Polish lady, ‘he wants to be up the pole’ said Eric. Back to the 2/1st Hospital to await our first posting as a unit, Dods took me to see some of his patients. Kerrod Voss, who had collected my golf clubs before we left Sydney, arranged for them to go on a transport, never to be seen again.

To Volos in Greece

We left Gaza by train to Kantara, crossed the Canal by punt and boarded another train for Alexandria. One of the men became ill with a high fever and was sent to hospital; when he recovered he would be sent to a convalescent depot and then to an army ‘pool’ where he would remain until his CO sent for him. They usually went back to their old unit unless young enough and volunteered for a combatant role. We arrived at a staging camp at Amirya, outside Alexandria. My chief memory of this sandy place was the tents, which were all unbelievably crooked and awry; and we were told that they had been put up by weary Italian prisoners. The next morning, we entrained to the wharves at Alexandria where we saw our soldiers chasing Arab pilferers, beating them with big staves.

We embarked in HMS Orion, the other ships were HMS Ajax and HMAS Perth. The ships’ officers gave up their cabins to us. On the backs of the lavatory doors were the outlines of enemy warships posted up. It was my job to go to the Sick Bay to see patients with measles; there I met the ship’s surgeon and his Petty Officer. I watched as they had their rum; we talked of air attack, they said that they lay on the deck and prayed. The ship’s defence was largely by the four-inch guns, there were also captured Italian Breda guns. Finishing in the Sick Bay I went to the wardroom and was told not to be surprised if a six-inch gun nearly above my head was fired. I went to sleep and was woken by a huge thump and there is still some slight deafness in my right ear. Our trip to Piraeus was smooth and uneventful. The Navy said they would be back for us in six weeks; we lined up and saluted them as Orion pulled away.

We went in open trucks to Kephissia, about 17 km the other side of Athens. The crowd called out ‘Australian Cowboy’ ‘Poly Kala’ or something like that. The officers were billeted in houses; I was in one previously occupied by Rudolf Hess2. We were entertained for drinks and a meal at the British hospital nearby. During the night it blew and snowed and a large tent was blown down and next day tinned butter was too frozen to spread.

We explored Athens and saw Evzones, the skirted Greek soldiers, outside their headquarters. de Burgh and I had steak for lunch at the Hotel Grande Bretagne. Also in the dining room was the Hellenic Commander-in-Chief, General Alexandros Papagos. There were many Greek soldiers in the streets with missing limbs, said to be from frost bite. Men of forty were being called up for active service. We went to the Parthenon, with Palestinian soldiers there. The British Club was open to us, where we drank whisky. Victor Coppleson went to a nightclub and was amazed at the gaiety, the Greeks were singing a parody on Mussolini to the tune of La Cucaracha.

Rex told me that I was to go to Volos, with two orderlies, to establish a Dressing Station and also to be the town’s Medical Officer (Military). We left Athens by train with Privates W.M. Hook and J. Lewis. The route was through central Greece to Larisa where we changed trains for Volos. On the carriage walls were scenic photographs of Greece which included one of Rupert Brooke’s grave on a Greek island. A Greek soldier came in and showed me the healed wounds on his legs. At Larisa we left the train and drove across rutted mud tracks to the train for Volos

It was after dark when we arrived at Volos with the blackout absolute, a sign that the town had been bombed. Lewis and Hook went with some Greek soldiers to their billets and I took a taxi to my hotel. I was shown into a large room on the first floor of the hotel which was blacked out by wooden shutters; cattle were lowing just outside. Being tired I went to bed to be dragged out of a deep sleep with a man running around the room pointing to the ceiling and calling out ‘airplanes, airplanes!’. This was my first experience of the over-sensitive Volos air raid siren which we had to learn to ignore if we wanted to get any work done. This time I took it seriously, put on a greatcoat and went down to the street. An English Officer there said ‘You are Australian’, to which I replied ‘Yes’, he then said ‘I hope they don’t drop a bomb on that destroyer’. A Greek destroyer was tied up at the wharf, and I was on the waterfront, with cattle from Salonica awaiting movement south.

Food at Volos was scanty, a tin of bully beef was a munificent gift to the locals and after we had made tea they asked for the used leaves. I had most of my meals at a cafe near the hotel and a kind man of the British consular service ordered my meals for me at first; fish was the usual thing. I had been told to contact Major Hooker, the town Liaison Officer.

I went into the street which was full of people and met a kilted Scottish soldier. I asked him did he know Major Hooker? He replied ‘He’s in bed, Sir’. ‘How do you know?’ I asked. ‘I’m his batman, Sir’.

Hooker turned out to be a rotund artillery man. ‘I should not be here; I should be in Singapore’. I hope for his sake that he did not get there.

He introduced me to Captain E.G. (Ted) Sayers, a New Zealand medical officer whose place I was taking, to Lieut Theodore Stephanides, MO to the Palestinian Dock Operating Company, and to the people at British Headquarters who said ‘We didn’t expect you, we have a perfectly efficient New Zealander doing the job’. Ted Sayers was happy to go back to the New Zealand army hospital at Pharsala. Later he became Sir Edward Sayers, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Otago University.

The next day Jim Lewis told me that they did not like their quarters with the Greeks, so I arranged their removal to the British barracks. Two days later they wanted to go back to the Greeks. From time to time on a Saturday Hooker drove me along the coast to a fishing village. He filled the car first with petrol in four gallon tins from a dump in the town; when we retreated dumps like this were blown up. The fishing folk were hospitable and offered us fried octopus tentacles which being strange we ignorantly refused. Then Hooker photographed the family, carefully arranging the groups. He told me afterwards that there was no film in the camera, ‘They like having their photographs taken’.

One night when driving in a new truck, with Hooker sitting at the back, he said the driver was an expert as he used to drive a London bus. We ran into some road metal, I tumbled over and came off minus a little finger nail, surprisingly there was little pain until they put some alcohol on it at the Greek Hospital.

Hooker introduced me to an attractive Greek lady in the theatre, she said ‘How do you do’ and applied the alcohol. On another occasion when in town with Victor Coppleson, we met Hooker who suggested we go to the officers’ brothel. I demurred but Hooker said that an inspection was part of my job. He drove us to what seemed in the dark to be a small cottage, we met Madame and her active partner Marguerite who was a bouncy middle aged European brunette. We sat in the small sitting room drinking Madame’s ouzo; Copp would not sit alongside Marguerite and insisted that I did. The phone rang, the girl went to answer it and came back saying ‘Marguerite say no zig zag until nine o’clock tomorrow’. Somehow we relaxed and went on drinking ouzo.

The site for the First Aid Post had already been chosen when I arrived in Volos. It was a three story building in a side street near the wharf. Our two men worked there in the charge of Lieut Stephanides, he did the sick parades for the Dock Operating Company. ‘Steph’ was an outstanding individual, he had been in Tobruk with this unit. He was a lean bearded man of about forty, an artilleryman from the First War. He was an MD of Paris for his thesis on the optics of the microscope. He insisted that the lenses in the English Watson microscopes were every bit as good as those in the German Zeiss microscopes. He was a radiologist in civil life, born in Corfu of a Greek father and an English mother, he spoke perfect English and Greek. He was also a naturalist and showed me detailed drawings of various species of insects he had made. He was a friend of the Durrells3 and he is mentioned in their books and features prominently in a subsequent TV series.

Steph organised a spleen survey of the children of the district and arranged for them to gather in the school hall of Agria. We examined their spleens, only one child had an enlarged spleen and he came from Salonika, so it is fair to assume that malaria was not endemic in the Volos district. When I was asked to have dead cows removed from the harbour, Steph rang the right people and soon there was a punt with men removing the cows. When I wanted to check the quality of the town’s water supply he took me to the Civil Medical Officer, and the matter was discussed over cups of gritty coffee. He introduced me to a local bank manager and I had a Sunday evening meal at the bank manager’s home. While the tea laced with brandy was appreciated there was no English and no Greek understood but they got the BBC on the radio for me to listen to the report of the Battle of Cape Matapan.

Steph was brave, one day when the Germans dropped a bomb on the quay, Jim Lewis said ‘That Stephanides, never turned a hair, cool as you like’. Steph said to me ‘I was terrified, I thought the building would come down on us’. A young English Lieutenant told me that during a raid he was on the railway quay, ‘I lay on my back watching the bombs leaving the planes and I was splashed by the water as they burst alongside’.

A chemist in the town had his shop and windows full of Burroughs Wellcome products, he said that he was going to give up the agency. Volos was said to be a town with German sympathies, certainly the stoves and pumps in the houses were made in Germany. I called on the town photographer to get some developer and fixer for a film. He showed me photos of Greek civilians killed by the high-level Italian bombing. I believe that the Germans killed few civilians as they went for military targets, such as ships from low level or dive bombing which was riskier for them.

The Greek Air Force Commander of the area was a very pleasant man; his unit flew planes from Almyros. I asked him about the air raid siren at Volos, he agreed that it was quite unreliable, ‘when it goes off in the early mornings I know the boys are back’. One day he told me that the forces the British had sent to Greece were totally inadequate. I could not comment but this man seemed to agree with the Royal Navy.

At seven o’clock each night I went to the meetings at British Headquarters. Major Murray of the Black Watch was in the chair together with an engineer who arranged to have sandbags put around the entrance of our First Aid Post. One night there was a request for weapons, shotguns, air-guns and revolvers to help defend the aerodrome at Almyros. Later an Australian Infantry Company was sent there, much to the distress of Major Hooker who said that they would riot. I reassured him and they turned out to be a quiet modest lot who had been fighting in the desert.

The Staff Captain at Headquarters knew less about the Army than I did. He told me to apply for what I needed through the usual channels, but neither of us knew what they were. A Staff Officer from the base came to Volos one day, he was Medical. I took him to lunch and upset him by ordering red wine, he told me how inappropriate this was. When I asked him for shell dressings and stretchers he said they were unavailable.

I had a note from Major Murray asking me to go to the Almyros aerodrome, to meet the Flight Lieutenant (Medical) and bring back a dozen bottles of whisky; he gave me a truck with a Cypriot driver. Almyros field was an undulating paddock, it was not surprising to hear later that the Germans did not find it. I was shown a fine water sterilising machine, and saw the obsolete Beaufort bombers provided to the Greeks. Twelve bottles of whisky was too tall an order and I was given six, they clinked and rattled on the way back to Volos over hills, in the blackout with dimmed lights, but my driver was very good. I wondered what he thought about whisky and/or the British Empire?

Note 1: The Augusta Victoria Hospital was built by Kaiser Wilhelm II in honour of his wife.

Note 2: Rudolf Hess one-time deputy to Hitler was born in Alexandra, Egypt and may have had some partial Greek ancestry.

Note 3: The Durrells were an English family of a widowed mother and her four children who lived on Corfu from 1935 to 1939 where they were befriended by Dr. Theodore Stephanides. Their engaging story is well known from books and a recent television series.

Part II of this series covering the dramatic but short histories of the 2/5 and 2/6 Australian General Hospitals in Greece will appear in the next edition of this magazine.