By MIDN Conor Byrne, RAN

This essay from the 53rd New Entry Officer Course intake won the Naval History Society prize.

Introduction

In modern naval doctrine the importance of maintaining technical superiority and effective joint operations practice has become one of the most significant contributors to the ability of a maritime force to successfully project power (Clark, 2002). The force multiplier effect of superior technology is relatively straightforward to comprehend. The impact of effective joint operation practice is harder to quantify however. Its effectiveness is determined by the successful integration of complementary forces and the synchronized application of all appropriate capabilities (Alexander, 2009). Whilst this practice has since been implemented and tested in almost all theatres of war by every service (Vego, 2009), it was the Battle of Cape Matapan that illustrated the importance of this lesson for the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Navy.

The Battle of Cape Matapan occurred off the coast of Italy between 27 and 29 March 1941, involving British, Australian and Italian naval forces. It was to be the last engagement of the 20th century involving a combined British force larger than a squadron (Simmons, 2011). Whilst the strength of the belligerents was comparative in terms of tonnage and capabilities, the losses sustained by the Italian’s were significantly disproportionate to those sustained by the Allies. It is the contributing factors for this disparity that are to be determined in this essay.

As such this essay examines the concept that effective joint operations and technological superiority have a significant force multiplier effect on the fighting efficiency of a naval group. This concept is highlighted by the examination of the belligerent’s capabilities and relevant geopolitical events leading up to the Battle of Cape Matapan. The impact of these capabilities and contexts of those countries involved is linked to the strategically significant events within the battles, as well as the resultant impacts on all sides. In summary a reflection of the links between the identified capabilities gained from superior technology and effective Joint Operations Doctrine is made to highlight their influence on modern naval doctrine.

Capabilities of Allies and Contributing Factors

In order to give a competent assessment of the significance of technical superiority and joint operations doctrine in maritime warfare the capabilities of each protagonist must be established. Maritime capability can be defined as the combined contribution of technology, leadership and tactics (Smith, 2012). Using this definition the following sections highlight the key elements that contribute to the maritime capability of both the Allies and Axis in the Battle of Cape Matapan.

The capability of the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy at this time was varied and is best understood by considering their strengths and weaknesses. Due to their number of vessels, in particular large vessels of a cruiser designation or higher, the Allies were able to project maritime force competently in the Mediterranean. The fleet was well equipped with effective guns, torpedoes and fire control (Rodger, 2011), however this force was largely aimed at what was then conventional maritime warfare – air power and submarine warfare were still entities that could not be totally neutralised with effective dedicated assets or weaponry (Johnston, 2014). Additionally the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) units were largely obsolete (Levy, 2012) however there were increasing numbers of torpedo bombers and aircraft on Malta and Crete (Brown, 2013). The allies did have, however, ASDIC sets for locating submarines on a majority of their vessels as well as some ship borne air and surface radar units on their large cruisers (Rodger, 2011). The British had also recently made breakthroughs in German and Italian signalling systems in the form of program ‘Ultra’ (Robson, 2014) which allowed a limited number of signals to be deciphered. This intelligence was supported by a competent network of informers (Robson, 2014) and regular aircraft reconnaissance patrols.

Thus it can be understood that the combined force of RN and RAN ships in the Mediterranean were competent war fighters with the technology they had, but they were limited by the nature of their task, the size of the area to be patrolled and their outmoded air and non-conventional warfare assets (Trench, 2011).

Capabilities of Axis and Contributing Factors

The capability of the Italian Navy was broadly similar to the Allies. It had a superior number of capital ships, equipped with modern fire control and superior calibre cannons (Lambert, 2014) and only a short distance to cruise between anticipated engagements and home port. The Italian Navy did not have, however, an equivalent of the Fleet Air Arm, and so was forced to request Italian or German air support thorough Naval Headquarters, when required (Vogel, 2012). It was also forced to rely largely on German reconnaissance and intelligence gathering with no real capability to verify or conduct competent reconnaissance patrols itself (Simmons, 2011). Whilst having vessels with modern damage control systems and layouts their vessels were not equipped with any form of radar as the Italians were not aware of the existence of such a technology (Simmons, 2011).

It can therefore be understood that the Italian capability in the Mediterranean was more than competent. As has been highlighted, the combination of superiority in tonnage, speed, calibre and geographic strategic and operational advantage combined to ensure the Regia Marina was a serious threat to the Allies.

Significant Strategic Events of Battle

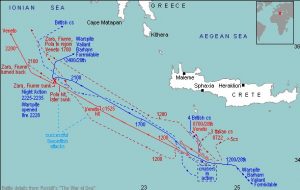

The Battle of Cape Matapan itself occurred between 27 and 29 March 1941. It was primarily a maritime engagement however aircraft on both sides had a decisive impact on the outcome. The battle itself can be simplified as three separate engagements. Figure one is provided as a reference to the following sections.

Surface action off Gavdos

Gavdos is a Greek island off the southern coast of Crete. The initial contact between the fleets, in which the Italian Admiral Iachino believed he had surprised the British cruiser squadron. The Italian squadron engaged with British and pursued them until being called off from the chase by Iachino. Once disengaged the British cruiser Squadron proceeded to shadow the Italian battle group, reporting their position (Trench, 2011) to Admiral Cunningham.

Air Engagement

Once Admiral Cunningham realized that he was unable to effectively close the distance with his own battle group he sent a flight of aircraft to attack. It inflicted no damage however it caused Iachino to reconsider his position as he was without shore based air cover and he turned his squadron for home. During a second wave of aircraft attacks an aircraft scored a direct hit on the Vittorio Venetocausing it to slow down with some controlled flooding. The attacking British aircraft was lost to anti-aircraft fire. Whilst in pursuit Admiral Cunningham dispatched a third wave of aircraft from his own aircraft carrier as well as those from airfields on Malta. Iachino managed to protect his battleship in the final aircraft attack but only at the expense of a direct hit to the Pola which lost steam and electric power control (Vogel, 2012).

Night Engagement

With Poladisabled but afloat Iachino dispatched a squadron of two cruisers and four destroyers to give assistance. Considering themselves safe in the darkness the Italian squadron closed onto Pola’s position and secured their main batteries, expecting no further action until light rendered their range finders operational (Simmons, 2011). The British cruiser Squadron, supplemented by Cunningham and his three battleships detected the Polastopped in the water by radar and were able to close to a range of 3500 meters. The Allied Squadron opened fire and in the ensuing four hours sank the heavy cruisers Fiume, Zara and finally the Pola as well as two destroyers.

Outcomes of Battle

The Battle of Matapan had a series of significant strategic outcomes for the allies. Most significantly it represented a change for the allies from sea command to sea control. Previously the allies only maintained sea control as they had a fleet that, when concentrated, was capable of effectively projecting maritime force around the Mediterranean. However, as identified previously, the allies’ commitments around the wider Mediterranean meant they were incapable of mustering this force consistently and so was unable to project a force strong enough to completely deny the strategic use of the Mediterranean by axis navies. Thus by definition they did not strictly maintain sea command. The effect of the outcome of Matapan on Italian morale and in highlighting weaknesses was decisive in influencing the Italian Navy that they were operationally and technologically incapable of effectively engaging the Allied fleet. Ultimately this outcome, along with the ability of the Allied navy to utilise joint operations doctrine to effectively utilise aircraft, contributed to the transition of the allied navies influence on operations in the Mediterranean from sea control to sea command.

Critical Reflection

The Battle of Matapan was not only instrumental in the successful outcome of WWII for the British and Australians but also in the demonstration of key doctrines that have gone on to shape maritime warfare conduct and theory.

As illustrated the use of superior technology in the form of radar and its successful integration with existing fire control systems was key in identifying the Italian fleet and closing it so accurately. The use of effective joint operations doctrine, specifically between the naval forces, the FAA and land based aircraft allowed all strategic assets to operate in the support of one another. This had the critical impact of overcoming the limitations of ships of the day which the Italians were unable to do.

These factors are only possible with support however and there were other factors that contributed to ensure the success of the allied fleet at Matapan.

The failure of the Italian Navy to develop an efficient night fighting doctrine was a fundamental result of the absence of comparable technology. As they did not have an awareness of the Allied capability their maritime warfare doctrine was fundamentally flawed and this contributed significantly to the magnitude of the defeat at Matapan.

The failure of the Italian Navy to develop an efficient joint operations doctrine is a result of a series of factors. Political, strategic and operational influences all contributed to creating a joint operations doctrine that was encumbered by procedure and marks of respect. The Italian Navy, in order to get aerial support from the Italian Air Force, was obliged to submit requests through Italian Fleet command which maintained only limited hours (Simmons, 2011). To obtain German air support required an extension of this procedure with a formal request being submitted to German headquarters Italy from Fleet command (Simmons, 2011). The net result of this was a joint operations doctrine incapable of definitive and timely action. The strategic impact was to cause air support to be so delayed in effect that it was considered ineffective in maritime support and subsequently largely dismissed as a waste of time by the Italian fleet command (Simmons, 2011). This then had the impact of forcing the Italian admiral to adjust his tactics to minimize the risk associated with an absence of air cover. It was for this reason that Admiral Iachino withdrew his battlegroup and sent only a part of it to assist the Pola: the risk from continued air attacks to his battlegroup was too high.

Both Admiral Iachino and Admiral Cunningham’s leadership style also contributed to the eventual outcome although mostly through the way in which they prepared their respective commands.

Cunningham was an early convert to the significance of air power in naval operations (Levy, 2012) and strongly believed in its place in modern warfare. Also as a result of his belief in the coming of age of night warfare (Finlan, 2014), which was made possible by the Royal Navy’s development of radar, the Mediterranean Allied fleet was trained and practiced in night warfare whilst under his command (Simmons, 2011).

Comparatively, Iachino was an officer educated and experienced in battleships and their position as the primary providers of maritime force projection. Whilst Iachino recognised the significance of air power, he allowed it to influence his tactical decision making and as a result did not pursue opportunities to destroy elements of the Allied fleet when encountered (Brown, 2013). It was the same influence that leads him to withdraw his main battlegroup from the stricken Pola and send only a small recovery detachment to retrieve her. Iachino therefore allowed his own bounded rationality in modern maritime warfare (Oladejo, 2014) to influence his decision making and leadership to the point of being overly pragmatic and cautious. Paradoxically Cunningham utilised new technology and previously untested theory to exploit opportunities and accepted the associated risk. In this case it was through the good leadership of Cunningham that superior technology and joint operations doctrine was able to be not only utilised but their influence as a force multiplier fully realised.

Conclusion

The outcomes of this engagement collectively highlight the impact of the technical superiority and joint operations doctrine on the development of modern maritime warfare doctrine.

Summarily the Battle of Matapan and later the attack on Taranto Harbour had the effect of neutralising the Italian Fleet. The battle itself was not decisive in settling the struggle for the Mediterranean – the Italian fleet still maintained more tonnage of faster more modern warships. It did however highlight the weaknesses in Italian naval combat effectiveness that originated as a result of inferior technology and ineffective joint operations doctrine.

Through superior technology in the form of radar, leadership in the form of Admiral Cunningham and tactics in the form of integrated and superior joint operations doctrine with aircraft, the Allies were able to ensure that their capability was maximised and sea command in the Mediterranean established. This combination was proved to be so significant a force multiplier that it caused the loss of 2,303 Italian crew and four capital ships for the loss of only three British men and a single aircraft. A better demonstration of the impact of effective joint operations doctrine and technical superiority cannot be given.

Bibliography

Alexander, K. B. (2009). Electronic Warfare in Operations: US Army Field Manual FM 3-36. DIANE Publishing.

Brown, D. (2013). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean: Vol. II: November 1940-December 1941. Routledge.

Clark, V. (2002). Sea Power 21: Projecting decisive joint capabilities. Department of the Navy, Washington DC.

Finlan, A. (2014). The Second World War (3): The war at sea (Vol. 30). Osprey Publishing.

Johnston, I. E. (2014). The Dominions and British Maritime Power in World War II. Global War Studies, 11 (1), 89-120.

Lambert, A. (2014). Mussolini’s Navy: a reference guide to the Regia Marina 1930–1945 by Maurizio Brescia 256 pp., over 400 illustrations, including maps, colour photographs and camouflage Seaforth Publishing. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 43(1), 236-237.

Levy, J. P. (2012). Royal Navy Fleet Tactics on the Eve of the Second World War. War in History, 19 (3), 379-395.

Levy, J. P. (2012). The Development of British Naval Aviation: Preparing the Fleet Air Arm for War, 1934–1939. Global War Studies, 9 (2), 6-38.

Oladejo, M. O. (2014). Bounded Rationality Constraints. Research Journal of Applied Sciences, 9 (1), 1-11.

Robson, M. (2014). Signals in the sea: the value of Ultra intelligence in the Mediterranean in World War II. Journal of Intelligence History, 13(2), 176-188.

Rodger, N. A. M. (2011). The Royal Navy in the Era of the World Wars: Was it fit for purpose?. The Mariner’s Mirror, 97 (1), 272-284.

Simmons, M. (2011). The Battle of Matapan 1941: The Trafalgar of the Mediterranean. The History Press.

Smith, K. (2012). Maritime War: Combat, Management, and Memory. A Companion to World War II, Volume I & II, 262-277.

Trench, R. (2011). Night Encounter: Aboard HMAS Stuart at the Battle of Cape Matapan. Quadrant, 55 (6), 86.

Vego, M. N. (2009). Joint operational warfare: Theory and practice. Government Printing Office.

Vogel, R. (2012). In the Tradition of Nelson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Canadian Military History, 2 (1), 17.