- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Nirimba

- Publication

- March 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The December 2021 edition of this magazine contained an article How did we get 16-inch Gun Projectiles to Australia?This came from the memoirs of Geoff Davidson, and using the same source the following has been collated outlining Geoff’s early career as an apprentice at Garden Island Dockyard.

I was born in Cowra and grew up on a farm on the Lachlan River 16 miles out on the Forbes Road. With irrigation we grew lucerne, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet corn and seed crops, and ran sheep and cattle. We learnt at a young age to drive cars, tractors, forklifts and fix them. I caught a bus from Gooloogong to Cowra primary with my twin brother to year 6. Along with my three older brothers we then went to boarding school, Yanco Agricultural High School near Leeton. Although earning a scholarship I left after year 10.

In 1973 I did a one year Pre-Apprenticeship course at Cowra Technical College, doing combined Automotive Mechanics and Fitting and Machining. This theoretically enabled us to complete a three-year apprenticeship instead of four. At the end of the year I applied for apprenticeships with Waugh & Josephson (Caterpillar), Qantas, Sydney Water Board and Garden Island Dockyard (GID). Mum and I went to Sydney late December for the GID interview. The very next day a letter arrived saying I had been successful. Based on pay alone, I selected GID as they offered a dollar or two more than the others (about $30.00/week).

I flew to Sydney the day before starting my first paid job, and my Uncle Don picked me up. I stayed with him, my aunt and cousins for about two weeks at their place in Gladesville. Before leaving Dad gave me $20 but also said ‘I still think you should be a sheep shearer.’ It was the first I had heard of it and glad I did not follow his advice. Uncle Don drove me from Gladesville into the city that night to show me where the bus would go, where to hop off, and where to get the GID bus at the end of Hyde Park.

First Year 1974

The first day Monday 7 January was fine except try giving a $20 note to a conductor on an early bus. She gave me a dressing down, but changed the money as we got closer to town and after she had more cash. I got off the bus too early, mistaking the hill at Pyrmont for the hill in Market Street, City. I was really worried that I would be late for work. I also remember being surprised when told I would not be working on Saturday – I thought most people did. We were all issued with two pairs of overalls, boots, safety glasses, hair nets for those with long hair near machinery, and a very good toolbox (Mine No 6029 engraved to identify owner). About a week after I started I was pleased to learn that my cousin Andrew (Jack Langfield) and ex-primary school colleague John Harley, both from Cowra, were also joining me. Jack was being trained as an electrician.

The shipyard was an awesome sight, with ships in dock, some tied up; sailors everywhere, the machine and boilermaker shops, the old buildings and about 4000 workers. We were given a grand tour, taken through workshops, fitted with green overalls and safety boots, advised what our programs were, etc. At the end of the first week we were told that we could take on additional studies in engineering certificates if we liked, and that we would be given additional lecture and study time if we accepted. The staff who did these courses were the ones in white overalls working on sexy things like weapons and radars. Although I had not known about these courses I thought why not – give it a go. I was 16 and 11 months old.

The first Thursday we were taken to Building 99, the green house, to collect out very first pay. This was exciting for all of us, receiving a cash of about $22.00, as we had only been there for three of the five days.

The first year we learnt fitting skills such as hand cutting, chiselling, filing, etc., from our Supervisor Bruce Grey and trainers Ernie Gardner and Peter Cunningham. We chiselled grooves in blocks of steel to make C-clamps, and filed blocks of steel to take hexagon shaped blocks through a plate. The hexagon block had to fit universally on any side and at any depth, to a very small clearance. We machined screw jacks. I was already pretty good from the last year at Cowra, and essentially got the best practical marks and finished mostly first. I enjoyed technical college too and mostly was the top of the class. Because I was ahead of the rest, I got ‘rabbits’ (dockyard slang for private jobs) to keep me busy. These jobs could be quite interesting. Once I modified an Australian Federal Police pistol barrel to try out a different bullet! We also had the ‘professor’ who worked on new-fangled inventions in a tunnel under Navy Headquarters. I was often sent over there to make different items for him.

A few months after we started I was to see first-hand the stupidity of unions (vs. the good). The dispute was not with management, the Government or Defence. It was an inter-union dispute. Historically toilet seats in the yard were wood, so these were fixed and replaced by carpenters. Enter the new age with plastic seats. Well, plastic, fibreglass and such like were in the realm of shipwrights, so they thought it was now their job. They both went on strike, and toilets could not be fixed, which meant that all other workers could not come to work, except apprentices. The strike went for over a week, and with rubbish bins full and rotting (ships still using them) we were only a few days away from being sent home on full pay.

During the year we worked on the decommissioned HMAS Anzac to remove a small steam engine and pump to be overhauled by the apprentices. We also spent several days at the submarine base HMAS Platypus pulling apart old torpedoes for decommissioning and disposal.

Second Year 1975

This was spent doing the rounds in fitting shops such as inside fitter’s workshop working on steam turbines, outside fitter’s workshop, diesel engine shop, small boats, and the drawing office in North Sydney. That year I received the first year apprentice prize for most outstanding first year (out of about 120 apprentices).

Inside fitters: initially I was in the inside fitters section at the main machine shop, working on reassembly of steam turbines into their housing. This was very fine tolerance work, scraping white metal bearings to bed the 6-8” shafts into each half. The first tradesman I ever worked with was Joe Piggott and his assistant and foreman Bob Johnson. It was interesting work but as ever, apprentices were set up for a good laugh. Regularly they would ask me to get a tool or device from the store room, where you had to write a chit for the tool loan. I got to know the storeman (Harry Geddes) and was sent there to get a ‘Long Weight’. Well I stood there for over five minutes, watching others come and go, but still nothing for me. I then asked again for the ‘Long Weight’ only to be laughed at and told I’d already had it. Gullible apprentices set up by tradesmen for a laugh. A few weeks later they asked me to get ‘a bucket of steam’ but I didn’t fall for that.

Nearby was the big hose testing bench. All ship system hoses had to be regularly tested for pressure, and here they would blank the hose on one end and apply the required static water test pressure at the other end. The pressure would often be many times the normal, and sometime the hoses would give way. Even though the pressure was only by a hand pump, the splash/noise from a hose failure would be good. Some hoses would grow like a balloon half way along.

Outside fitters: in this workshop we worked on all services equipment in the shipyard. This included ship cranes, boiler rooms for hot water to ships, mobile cranes, power generation and underground tunnel water and drainage services. One of the first jobs was to fit a car air conditioner to a mobile crane, as the drivers suffered severe heat with the sun on their glass canopies. The fitter and I had to do a lot of cutting on the canopy, install the air conditioner and the pump on the engine. Ultimately the air conditioner was too good and the drivers were freezing with the car unit cooling down a small one seat space within the mobile crane.

I remember one day it was just pouring, three inches of rain in a few hours. No one could work outside and I was given a chit to be issued with heavy duty raincoat, hat, pants and gum boots. A mate and I then just walked all over the shipyard, visiting other apprentices, looking around, safe that no one would come out and challenge us. I still have the raincoat.

Another job was working on all service tunnel drainage pumps around the dockyard. You could go down an access hole and just keep walking and checking pumps, and then when you found another access hole pop your head up just to see where you were.

Boiler house maintenance was another job. These boilers went 24 hours for the ships and so maintenance was constant. Often it was replacing leaking valves, re-lagging pipes, etc. It was fairly slow work and on very quiet days I’d either catch up on homework or rarely have a sleep up on the second floor of the boiler house.

Another interesting job was maintenance on the dockyard standby generators which were located under the tennis courts. There were three huge old diesel engines and generators, all installed during WWII. The water cooling for these was via heat exchangers with cooling water coming straight from the sea. Algae would block the pipes over time and the solution was simple. Draw in cold seawater and return warm water for a set period of weeks, and then reverse the flow so that cool water went down the warm pipes. The algae and growth would essentially get influenza and die.

Diesel shop: in this shop all diesels were overhauled and tested on a dynamometer. This was a fairly busy area and quite interesting. My first job was to pull apart a large turbo charger about 1 m diameter and check its blades, bearings, etc. There were large Paxman engines and very impressive Napier Deltic engines off the Mine Hunters. Deltics were just like a triangle with the crankshafts at each corner, with opposing pistons in a common bore. They were a project within themselves. One of the young foremen there was Gary Nelson, also an ex-Cowra boy. Again there was a strike on while there, so I took the head of cousin Jack’s Morris 1100, overhauled it, and had it back the next day.

For about six weeks of this posting I was sent to the Miller Street North Sydney drawing office for draftsman training. This was very good and I managed to complete some technical drawing assignments for both my courses. On a few occasions I was asked to do the daily mail transfer by waiting outside the building at 9.00 am for the mail truck. Having grown up with four brothers and attending a boys’ only boarding school, it was wonderful looking at all the office girls going to work.

Small boats: this was where the smaller navy boats including Torpedo Recovery Vessels (TRVs) were maintained and repaired. The wooden hulls were done in the nearby shipwright’s shop (they had long steam boxes where timber would be steamed and bent and dried into shape). Small boats worked on the engines, gearboxes, propellers fitting, rudders, etc. My foremen were Mick Piggott, Ray Ami and Mick Kipprioti. There were peaks and troughs in work and on some days I did homework or slept on a remotely moored boat. At one time we took a TRV on trials all the way to Manly and I swear we nearly rolled going across the Heads. We came back via Lady Jane Beach, the known nudist beach remote from streets but accessible to boats. I was impressed. I also remember working on an old oiler vessel. It had twin funnels like a paddle steamer, and German diesel engines. I also travelled by boat many times to work at the ‘Sayonara’ boat facility over in Rushcutters Bay.

I finished second year here and we all had the annual Xmas drinks and fun on the last day till 12.00. My cousin Jack drove to the sheds to pick me up and go back to Cowra. When we were departing everyone came out to say goodbye, he started off and the EH Holden went about 2 feet and CLUNK – a hard stop. We were shocked but everyone was laughing – they had put a small steel rope around a bollard and the tow ball of the car.

As I understand, about seven years later a few were caught up in scam stealing equipment from Defence. Found on a property were diesel engines, the old Bailey bridge which allowed trucks to drive up onto the aircraft carrier, and other items. Also work that was done on private boats at the yard up in Ryde and billed as Navy.

I did my entire Fitting and Machining course at Meadowbank Technical College, and about three years of the Engineering Certificate. For many of the Engineering studies I attended Technical College at night, with three hour sessions ending at 9.00 pm. The bus timetable back to Ryde was not so good so I mainly walked the three km or so. In 1975 I had become disenchanted with the night school and just stopped going for about two weeks, but fortunately decided I should slog on and went back. This was a pretty important decision, as it influenced where life took me.

Third Year 1976

Third year in 1976 was spent in the main machining shop where I quickly rose from using one of the average lathes to using one of the best. I ended up on an excellent large 2 m long 4-jaw chuck Dean, Smith and Grace lathe and was given tasks such as machining steam valves, odd items of large size and machining large 8” (200 mm) billets down to 3.5” as bolts (rudder bolts for HMAS Supply). Because I kept waiting for the crane to lower the billets into my lathe, I started lifting and hand loading them myself. That is when I hurt my back, was sent to the doctor (Dr Death on GID), given a couple of aspirins, and sent back to work. It was never the same again. I was so quick at roughing out the bolts oversize from the billets, that they then had me machine them to final size, drill 20” (500 mm) deep grease holes through the centre, machine the thread, etc. They had a French machinist doing this as well, and in the end he complained that I was doing them too fast and had to slow down. I told him I had to keep busy to make the day go by.

At one stage when I temporarily had no job, I decided to totally clean the lathe. It really came up well and that was when they gave it to me to use at work, stating I showed interest (they were meant to be cleaned by the tradesman assistants, but the unions could not prevent apprentices from doing these tasks). When the light bulb blew I just went to the electricians shop and obtained a new globe, and went back and put it in. I was gently approached by the electrical union and told that job should be done by an electrician and not to do it. I replied we replace our lights at home, and I’m doing mine here (as an apprentice). After that the foreman had me quietly do any replacements as required. I support unions in many ways, but I couldn’t abide by such rigid restrictions.

Again I was gullible. One day there was no job for me, so the foreman asked me if I could make a replacement hot water jug wire element for the old ceramic jugs that you put new elements in when they blew. My foreman was strict and I did what he asked, not realising I was being set up. I grabbed the element, went to the electricians store, and obtained wire of the same resistance – a miracle. When I got back he asked me to coil it to go on the ceramic body. I pondered how to do that and decided I could get a thin threaded rod in the lathe, turn it slowly and feed the wire through a light clamp and around the thread. It nearly worked other than not being small enough so he got a surprise and a big laugh. He then sent me to the electricians store for a standard replacement element they had in stock.

The variety and size of threads, in steel, aluminium, brass, plastic, stainless, right and left handed I had to machine was truly astounding and few machinists these days would experience it. Because we had British and American ships with equipment from the Continent, we had a large variety of threads. For British ships we had British Standard Whitworth (BSW), British Standard Fine (BSF), British Standard Pipe (BSP for pipes), British Association (BA) instrument threads, Brass for instruments, Bicycle, Admiralty thread for fire hose fittings, and Metric coarse and fine for the Dutch systems. For the American ships we had Unified National Coarse (UNC), Unified National Fine (UNF), National Pipe Taper (NPT for pipes), and Conduit threads for electrical tube. Later in Weapons group we even had European Bottle top thread identified in the Machinists Handbook.

A tradition for some of the workers was to spend 30 minutes of their 40 minute lunch break at the Frisco Hotel. The Frisco would have a cargo van outside the gate and at 12 noon the workers would dash for the van. Sometimes there would be twenty or more crammed in and the van would be low to the ground. At twenty-five to one the van would leave the pub and stragglers had to walk back. In the machine shop there was a noticeable chunk of concrete missing four metres high up on the concrete wall. We found out that a few years earlier one of the machinists had returned from the pub maybe not sober and started his work. The piece of steel in his lathe was not in properly, and when at high speed the lathe had spun the work out and onto the wall.

Every Thursday after lunch was payday with cash in hand. After work there was a gathering at the Frisco Hotel, in particular apprentices. We would regularly drink to 6 pm when it closed and then go home. That worked well as it kept us out of trouble. We got to know the publican and his regulars very well. On our last day of work before Xmas, we would often start at the Frisco with a few beers, before work at 6 – 7.30 am.

Fourth Year 1977

For our last year we were given a choice of about three places. Because I put down machining as my third choice, that’s where they sent me because no one ever put down machining. I decided that was not a good long-term choice and went to the apprentice supervisor, Norm Liddell to ask for something different. He just that day had had a visit from the Weapons Group asking for a suitable apprentice to learn gun plot mechanical computers with the looming retirement of a current worker. They wanted an apprentice who potentially would become a technical officer and was therefore doing an engineering certificate. Prior to this, no apprentice had ever worked in Weapons, a sort of elite restricted area. I jumped at the opportunity. The next day they sent me to Weapons group for a half day demonstration of what they did. They had me spend about two hours in the large hydraulic test room watching the complex tests done of submarine dive control units.

I started with Ray Quill working on the overhaul of the Admiralty Fire Control Box 10 (AFCB 10), a mechanical computer that calculated range, bearing, rate of change, gun elevation, taking into account wind speed and direction, barrel wear, etc. for the 4.5 inch guns. It was very complicated and I liked working on it. I had to replace many miniature bearings and reset the small gear clearances to remove errors. Few parts were available and I remember oxy welding a bit onto a gear to replace a broken tooth, then hand filing to size using a gear testing machine. After we overhauled most sections over the next six months, we then went to Cockatoo Island every day to install it in HMAS Yarra and set it to work. Initially we were required to sign on and off at GID every day, then wait for a boat to take us there (40 min) to Cockatoo, so we effectively worked about 9.00 to 2.30 every day. We still had to go back every Thursday to collect our pay at lunchtime. After some time management relented and let us start and stop work at Cockatoo Island.

There was one morning and afternoon ferry from Balmain to the Island so they could not be missed. Eventually Ray got sick with a heart murmur, so I worked at Cockatoo by myself (apprentices were always meant to be with a tradesman/supervisor). There were Cockatoo Island employees around and sailors. Twice when the Weapons system bosses including Allan Foxcroft from GID arrived unannounced they found me head down bum up working away on the computer.

I remember working under the AFCB 10 box with the whole computer wound out and lying horizontal, with the back of the computer exposed in the same plane as a table. The gap from the front of the computer (laid down) to the deck was about 12” (300 mm). I was doing work laid on my back with my head squeezed between the deck and the computer, and my arms up inside the computer. The computer had 400v DC ‘Metracells’, which were bare to mild electrocution. As I lifted my head it hit one of these. Of course the reaction was to quickly lower the head, which then thumped onto the deck. The reaction then was to lift resulting in another shock from the Metracell. I crawled out holding the front and the back of my head. Somewhere about in this time I remember Elvis Presley died.

Cockatoo Island Dockyard was very old, historic and interesting. In the convict days it had been a jail, built from the local sandstone. This jail was the administration area, in good condition other than worn steps at the doors. Originally a number of large grain silos were carved into the rock in the shape of fat bottles, about 10 m in depth. Some of these were exposed due to buildings being set back in cut out areas. The old ship building slip way was still intact, and I believe the last ship built there was HMAS Success, in the 1970s. The bollards used to tie up ships in the dry dock were all old ship cannons, sunk into cement. Near our change rooms was the foundry where large ship propellers were once cast and the casting holes were still there. In the machine shop there was an old steam turbine wheel with blades, about 600 mm diameter. The plaque on it stated it was on an RAN ship on the east coast of Australia during WWII, when a Japanese sub fired a torpedo at it hitting the propeller and blowing it off. With the ship under full speed, the engine turbine over-revved so much that the turbine permanently grew in diameter beyond use (beyond its elastic limit). Cockatoo also had the landmark Titan floating crane. In the 1980s it was sold off to an Asian scrap yard, but capsized not far north of Sydney under tow. There were rumours of it being sabotaged by people not wanting it to go to Asia.

HMAS Yarra had a MRS3 Fire Control Radar Director up top, where an operator could also use very powerful magnifying sights to target distant objects. Ron, the Ikara missile expert from Weapons, took great advantage of these at Cockatoo having a peek at ladies sunbaking nude across the waters, safe in the thought that no one would see them with any clarity.

I eventually went to sea on Yarra working on the fire control computer. The first day out I got a little stomachache working down below and about a third of the way back from the bow. I went topside and had some good breaths and got my bearings, and I’ve never had a problem at sea since. We had the 4.5” guns firing which was spectacular for me, and some dummy torpedoes fired for practice at us from a submarine.

People I recall working with include Stan Bridgeman (retired to Mudgee), Nick Roogaveen, John Ralphs, Greg Snook, Paul Gazzard, Dick Stubbs (all Gyro compass fixers), Glenn Thornton, Ron Johnson, Andy Cumicich, Bruce (?), Brian Bingham, Geoff James, Brien ‘Buddy’, Geoff Hoff, Chris Gordon, Les Dewhurst, Tasha Vanos, Bill Taroni, Stewart Marshall (went to Griffith), Bob Hollingsworth (from Canberra) and Ross McBay.

The Weapons group had their own excellent small machine shop with lathes and milling machine. Originally they had two machinists in there, with the senior machinist being very particular about who could use the machines. When I first needed to do some work, he looked over me like an eagle to check my skills. After a few jobs, he said ‘Geoff – you can use this shop any time you want’. No other staff member in the building was given that permission. Staff (tradesmen and technical) asked me to make parts when the machinists were away and it always put me in good stead at all levels. For a year or so after the two machinists retired, we had a young Scot called ‘Jock’ as the machinist. He often came into the clean room workshop and was known to take bits of food left on work benches – chips, Minties, etc. We set him up one day by inserting a large charged capacitor in an open packet of chips, with the wires exposed. He came in to Ross McKay’s bench next to me and asked if Ross was around. I said no, so he said he might have a chip. He put his hand in and ‘WHACK’ he got a shock. He danced back spinning and swearing, to which half a dozen staff were rolling about laughing.

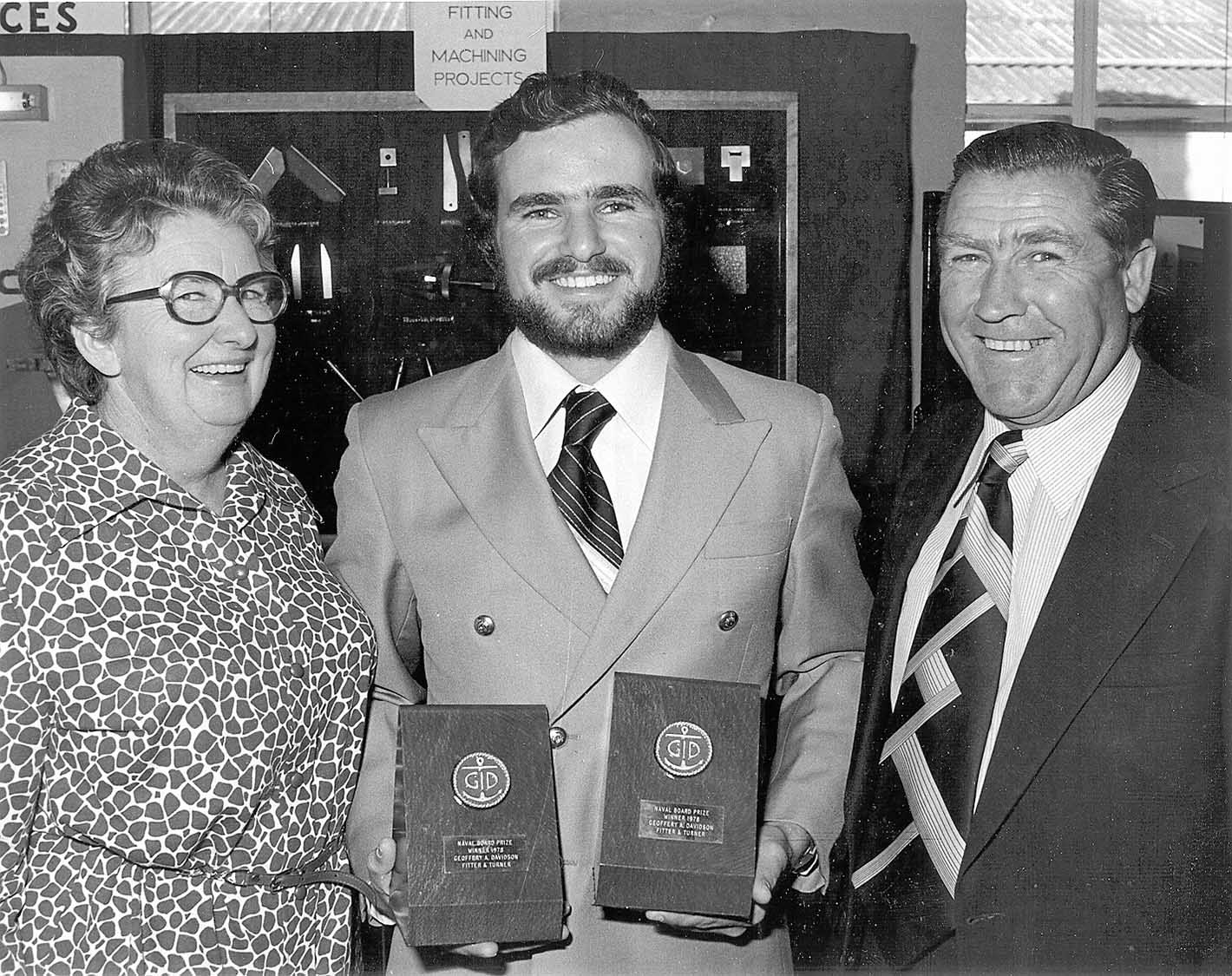

The year after I finished my apprenticeship, the annual apprenticeship award day around September was held. Along with a few others I was nominated for Apprentice of the year (Admiral Bernard prize), and the Naval Board prize for the most improved apprentice in last two years (basically second place). Two of us were fitters and machinists, the other being John Harley with whom I had gone to primary school in Cowra. He had continued machining in year four, and was now an apprentice trainer for GID at the new location at Rosebery. He and I were to have a machining competition with a project done on a lathe, shaping machine and milling machine. Gulp – I had used the Weapons group lathes and milling machines on and off for different work but he had been on them for much longer – oh well. We had two days to complete the competition and ran neck and neck all the way. We both made a few minor errors, but in the end I finished first to specification. So I was awarded the Naval Board prize, missing out on the Admiral Bernard prize to a foundry maker apprentice by the flip of a coin.

This was the end of Geoff’s apprenticeship and he was to continue at Garden Island as a Trainee Technical Officer, eventually rising to become a Project Director in Defence Electronics Weapons Systems Division, but that is another story.