- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Naval history, History - WW1, Submarines

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS AE1

- Publication

- December 2018 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This important commentary by Rear Admiral Peter Briggs AO CSC RAN (Rtd) provides a summary of research that led to the successful discovery of the remains of AE1by MV Fugro Equatorand further examination of the wreck by the Research Vessel Petrelin April 2018.

HMAS Australia’s Signal Log

A short annotation in the signal log of the flagship of the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet, HMAS Australia, of 14 September 1914 reads:

8:15 pm (sic) HMAS AE2 to Flag, Submit had AE1 a destroyer scouting with her today. She has not yet returned to harbour.

Thus began the story of the loss of HMAS AE1, Australia’s first submarine, whilst on patrol off German New Guinea on 14 September 1914. For over one hundred and three years it was lost. The finding and positive identification of the remains of AE1on 20 December 2017, solved the RAN’s greatest outstanding maritime mystery.

The Submarines HMA Ships AE1and AE2

In December 1910 two E class submarines were ordered by the Australian Government and delivered from their builders in England at the end of 1913. AE1and AE2were primitive by today’s standards, but were state of the art in 1914.

They had riveted steel hulls, displacing 800 tonnes dived, 4 torpedo tubes (one forward and one aft and one on either beam) with 4 reloads and a dived operating depth of 100 feet (30 m). They were fitted with two diesel engines giving a maximum speed of 15 knots on the surface. Two electric motors and banks of lead acid batteries provided a maximum dived speed of 9 knots for a brief period, or 5 knots for 9 hours. The crew of 35 was a mixtureof Royal Navy submarine personnel on loan and volunteers drawn from the fledgling RAN.

The submarines were commissioned into the RAN on 28 February 1914 in Portsmouth, where they were fitted with a medium frequency Wireless Telegraphy (WT) set and a gyrocompass. The passage to Australia was extremely arduous and set a world record for submarine voyages at the time. Numerous technical challenges were overcome before reaching Sydney on Sunday 24 May 1914. Each submarine had travelled about two thirds of the 12,000 miles from Portsmouth to Sydney under their own power, and was towed by their escorts for the remainder.1

The submarines underwent a three week docking in Fitzroy Dock at Cockatoo Island during June. Their refit was truncated as the news from Europe indicated that war was on the horizon.

Outbreak of war: deployment to New Guinea

Shortly after the declaration of war on 6 August, at the Admiralty’s request the Australian Fleet deployed to New Guinea to capture the German colony and its important wireless station. AE1sailed from Sydney at the end of August to rendezvous with the other fleet units in the Louisiade Island chain south-east of New Guinea on 9 September. The fleet, including the two submarines, entered Rabaul and nearby anchorages on 11 September and successfully captured the WT station and the German colony – but that is another story.

The submarines were employed guarding the approaches to the landing anchorages against a potential attack by the German heavy cruisers, Scharnhorstand Gneisenau. A torpedo boat destroyer accompanied the submarines on their patrols; AE2and HMAS Yarraundertook the first patrol on 13 September, HMAS Parramattaand AE1patrolled on 14 September.

From the account of Lieutenant Dacre Stoker, the Commanding Officer of AE2, we believe AE1had a defective port shaft, limiting her propulsion, dived or when going astern, to one shaft. This defect would have greatly handicapped any recovery from a depth excursion or flooding when dived and reduced the astern power available on the surface. Both shafts were available propelling ahead on the surface under diesel propulsion. Arrangements had been made to rectify the defect that evening – in retrospect it seems extraordinary that AE1was at sea on the 14th.

Parramatta’s brief account of the day’s events2is the primary source of what occurred as none of the signals that passed between them on that day was recorded by any other ship, nor have we been able to locate any record of the Board of Inquiry that was ordered by the Fleet Commander. It does not appear to have been convened – perhaps overtaken by the exigencies of war?

The method of passing signals between AE1and Parramattaon this fateful day is not known, as we have not located Parramatta’s signal logs. WT could have been used but .would have required AE1to rig her wireless mast, a cumbersome, time-consuming and manpower intensive operation. Since the submarine would have had to unrig it prior to diving this seems an unlikely proposition for a submarine heading out potentially to intercept the enemy. Communications could either have been by flashing light or, more likely, by megaphone.

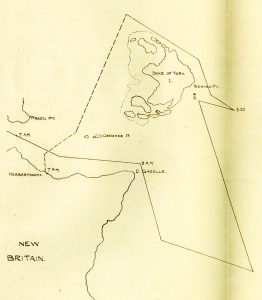

After rendezvousing at sea on the morning of the 14th AE1and Parramattaparted company, the latter patrolling to the southward off Cape Gazelle and AE1proceeding to the northeast towards the Duke of York Islands. This diversion is believed to be to investigate a report of a German steamer sighted by Yarraon the previous evening. Parramattaturned north to close the submarine later that morning and reported that they were close to AE1,located in a position 2 miles off the southeast corner of Duke of York Island at 1430. In response to a query from AE1, Parramattaadvised that visibility was approximately 5 nautical miles (a tropical afternoon haze is common in this part of the world).

AE1 fails to return

At 2015 AE2,alongside the submarine depot ship SS Upoluin Rabaul harbour, was concerned about AE1’s failure to return as expected and raised the alarm. Yarraand Parramattasailed to search for AE1at 2320. Using searchlights and flares they circumnavigated the Duke of York islands and searched to the northwest for 30 nm to cover likely drift on the strong tidal stream. The cruiser HMAS Encounterjoined the search at first light (0545) before anchoring at 1045 and the destroyer HMAS Warregore-joiningfromKaviengto the north joined in late morning en route to Rabaul. No trace of wreckage or bodies was found. Encounterreported an oil slick, but assessed it as originating from a passing ship as it had dispersed by midday – no position was given for the slick. Motorboats and a steam yacht were used to search the adjacent coastlines, without success.

Extract from HMAS Parramatta’s Track Chart accompanying the Report of Proceedings for 14 September, 1914. Australian National Archives:

AE1was under strict instructions to return to the anchorage in Rabaul Harbour by dark; sunset was at 1750. This directive was reinforced by a personal signal from the FleetCommander as she sailed that morning, it is believed that this would have had a significant impact on the actions of the Commanding Officerof AE1.That afternoon the Fleet Commander, en route to Sydney in Australia, advised the Naval Board that AE1 with a crew of 35 was feared lost.

The final search for AE1

The initial analysis of the Find AE1 Ltd. team favoured a grounding on the fringing reefs of the Duke of York islands. In November 2015 Find AE1 Ltd. undertook a multi-beam echo sounder search of the reefs along the route back to Rabaul. The equipment had a good capability to detect AE1down to a depth of 200 m. The probability of locating her fell off rapidly in deeper waters. No sign of AE1was found close to the reef edges, effectively ruling against a grounding as the source of the loss.

The Find AE1 Ltd. team went back to review all the original records. Two significant changes resulted; the simple tracing of Parramatta’s chart was scaled onto the modern chart and adjusted to a whole number of minutes of latitude and longitude on the basis that it was a rendezvous (explaining how Parramattawas able to steam directly to AE1’s position, despite the limited visibility).

Secondly, an extra hour in the life of AE1was noted – the last known position was timed in the original report at 1430, not 1530 as Parramattahad signalled in later reports.

From the adjusted last known position and with an extra hour, AE1had sufficient time in hand to undertake a practice dive. Given the hitherto lack of dived training opportunities for AE1and AE2, this became the favoured scenario. The search was oriented around her route back to Rabaul – exactly where she was found in December, lying on a heading for Rabaul.

Plans for a 30-day towed side scan sonar search of the area (the cheapest option) were hastily shelved when Fugro (a Dutch off-shore resources exploration company) offered the availability of the highly capable search vessel Fugro Equatorwhen a survey off PNG was completed. The ship (which had conducted the search for Malaysian Airlines missing Flight MH 370) was fitted with hull mounted multi-beam echo sounders and a sub-bottom profiling sonar. However, more importantly, the embarked Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) carried a similar capability, plus a side scan sonar. The AUV’s ability to ‘fly’ 35-45 m off the bottom whilst searching, effectively removed the depth of water as a factor. As the survey team explained it: we are looking for a 54 m long submarine in 35 m of water – as long as we are looking in the right place we will find her.

The search cost was capped at $1M as the practical limit for fund raising in the short time available before the ship left PNG waters. Negotiating a fixed price contract and raising the funds was the next challenge. The most difficult of these questions was solved by a generous personal guarantee from John Mullen, Chairman of the Silentworld Foundation, to meet any shortfall in sponsorship to be raised by the Foundation up to a 50% limit. The Federal Government (Navy) contributed the balance of $0.5M. The Submarine Institute of Australia, a founding sponsor of Find AE1 Ltd., provided a loan to cover GST costs and further sponsorship at short notice. Fugro undertook to complete a comprehensive search of the area, estimated to take 12 days at a cost of $1.7M and to bear the risk of additional costs over and above the $1M cap, including from weather, equipment failure or miscalculation of the task.

Two hours after commencing the first line if its search the AUV detected AE1 on its side scan sonar. This was quickly picked up by the analysts 18 hours later after recovering the data from the AUV at the end of the first search.

The AUV was re-programmed to undertake a series of runs around the contact to build up the sonar picture. On completion, what looked like the outlines of hydroplanes at the bow and stern of the contact could be made out and it was decided to stop the search and inspect the contact with a drop camera. Within 30 seconds of the camera coming in range of what turned out to be the bow, AE1was positively identified – the last resting place of thirty-five of Australia’s first submariners.

This was the thirteenth search for AE1. The RAN had mounted a number of searches over the years and we followed in the footsteps of Commander John Foster, who organised the majority of the remainder and wrote a book recording his efforts.3The major contribution to success on this occasion was undoubtedly the AUV technology; but the comprehensive research combined with some submariners’ intuition also played a role.

The images gained from the drop camera and a third sortie by the AUV to photograph the wreck gave a good overall understanding of the wreck’s situation – it had clearly exceeded its crush depth and imploded – but why?

This question was solved in April 2018, when Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft, generously offered Find AE1 Ltd. the use of his specialised ship, the Research Vessel Petrel, fitted with a highly capable Remotely Operated Vehicle [ROV] carrying two high definition video cameras. The West Australian Museum and Curtin University provided the benefit of their experience filming HMAS Sydney(II) and the German auxiliary cruiser, Kormoranoff Western Australia, and joined the team with experts from the Australian National Maritime Museum and Find AE1 Ltd. to undertake a two-day detailed photographic examination of the wreck.

Cause of the loss of AE1

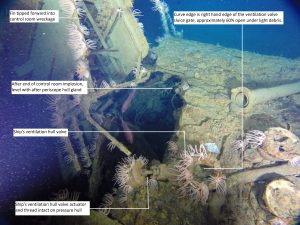

In the course of this it was discovered that AE1’s ship’s ventilation valve was two-thirds open – it should have been shut before diving. We don’t know why this valve was left open – it could have been an equipment failure; the rod gearing to operate the valve could have jammed, a ‘hard open’ valve may have felt as if it was shut on checking, or it could have been an oversight. We don’t know why.

The open valve would have permitted seawater to enter the engine room, quickly making its way to the bilges and causing electrical short circuits, probably leading to a loss of propulsion and lighting. It would have been very difficult to recover from this situation. Shutting the eight hand-operated main vents valves and blowing main ballast tanks would have been hard to achieve against the noise and disruption caused by the flooding.

It is surmised that control would have been lost soon after diving and as the submarine sank deeper, the rate of ingress would have increased dramatically, flooding the after end of the submarine whilst causing it to exceed its likely crush depth, estimated at 90-120 m. The resulting implosion over the forward section of the submarine would have been a high energy event, causing a shockwave that would have killed the crew instantaneously.

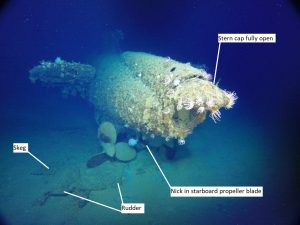

The submarine appears have impacted the hard bottom on the skeg supporting the rudder, displacing both along with the after-hydroplane guards, before falling forward onto its keel. The second impact snapped off the forward hydroplane guards and broke the back of the submarine at the forward end of the keel.

This analysis has been confirmed by external experts as a reasonable interpretation of the clues. A full report is available on the ANMM’s website.4

Two important steps remain outstanding: the joint declaration by PNG and Australia of a protection zone around the wreck to guard the wreck from trophy hunters or interference by salvors, and ensuring that it is treated with the respect due the grave site of Australia’s pioneer submariners.

The collection of environmental data on the site for 12 months will enable future management decisions for the wreck to be made.

The successful AE2 Commemorative Foundation and Find AE1 Ltd. team are considering establishing a company, the Australia E-Class Submarines Foundation (AESMF) Ltd., to protect, preserve and tell the story of Australia’s first submarines. Further details are available on the Submarine Institute of Australia’s website.

Notes:

1 The story of HMA Ships AE1and AE2is well described in Stoker’s Submarine, by Fred and Elizabeth Brenchley, published by ATOM, 4th edition 2013.

2 Darren Brown’s meticulous research uncovered most of these documents.

3 Entombed But Not Forgotten, John Foster, Australian Military History Publications, 2006.

4 https://www.anmm.gov.au/about/media/media-releases/media/2018/09/13/05/12/ae1-survey-report