- Author

- Ross, Trevor Wilson, OBE, Captain, RAN

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 1975 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Captain Ross’ career with the Royal Australian Navy spanned a period of 38 years – from the torpedo boat destroyer to the jet operating aircraft carrier. He joined the RAN with academic qualifications and specialised in the Engineering Branch. He served in both Australia’s in two World Wars and played an important role in the transition from gun to air power. Captain Ross tells his story as a sailor and recalls with vivid clarity fellow officers who contributed to the genesis of the Royal Australian Navy.

I WAS BORN IN HOBART on 24th April 1888, and in due course matriculated from the Friends’ School in that city. After gaining my Bachelor of Science degree and, subsequently, Master of Science from the University of Tasmania, I was admitted to Trinity College, University of Melbourne. Here I completed my course for BME degree with First Class Honours. Our Engineering Professor was the world famous ‘Bally’ Kernos. The Professor, I remember, possessed a steam car and on one occasion he allowed us students to build on to it a replica of a Victorian locomotive and in this contraption we paraded through the streets of Melbourne in the University Procession with many stops and adventures!

On leaving Trinity College, I was appointed Research Assistant to the Chief Inspector of Mines in Victoria and had a lot of interesting times in the very deep mines of Bendigo before they were flooded, and later in trying the hopeless task of pumping them out.

In 1911 I learnt of the RAN Scheme for University Graduates and was interviewed by the Naval Board later in the year along with many others – all Sydney men – and as a result I was appointed Probationary Acting Engineer Sub-Lieutenant on 1st February 1912, and so became the very first officer to join the RAN under a regular Scheme. All others at that time had been casual appointments from various walks of life – some ex RN, some ex RNR, some ex Merchant Service and some from the various State navies. Among these officers were Admiral Cresswell and Engineer Captain Clarkson.

After a few days to gather a skeleton supply of clothes, I joined HMS Encounter with absolutely no training as to the ways of the navy. I was treated as a weird specimen but surprisingly got on very well. The Commander was J. B. Stevenson, who subsequently turned over to the RAN. After a trip looking for a lost dredger in the Tasman Sea and a few days in Wellington, Encounter paid off on 21st June 1912, and became HMAS – her crew, including me, mostly joined HMS Challenger and off we set for England. Clarence Bridge (later Captain C. Bridge, OBE, ED) joined me and we had a very happy trip with long stays at Fremantle and Colombo, finally arriving at Devonport to pay off into Reserve on 10th October 1912.

After spending a few days in London I was appointed to HMS Inflexible, then refitting in Chatham Dockyard. Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, was most alarmed at the leisurely three months’ refits of capital ships and stressed that Germany could outnumber the Royal Navy by choosing a suitable period when all German ships were at sea and a large number of RN ships were in dockyard hands. As a result, the First Lord decreed that future refits should be completed in one month.

Inflexible was the first to do so and was, of course, a matter of great interest to all and was continually overflowing with visitors. This did not upset the dockyard mateys one little bit – a shipwright working (?) outside my cabin took two days to put a new handle in his hammer!

However, Inflexible was appointed as Fleet Flagship in the Mediterranean and I was transferred to Lion. Now this was a very ‘hot’ ship in the days of Jacky Fisher’s drive for efficiency versus yachting. Admiral Luigi Bayly, Captain ‘Figgy’ Duff and Commander Hyde Parker were formed into a team to obtain results.

Lion and Centurion were the first ships to be fitted with Percy Scott’s Director firing and so we had to be always at it – in 26 weeks we burned 25,000 tons of coal, which meant coaling ship every weekend and getting rid of all the ashes. Churchill came to Portland almost every weekend and he and Luigi Bayly would go for long walks hatching plans for new exercises. The result was that at 2.00 a.m. on Monday we would raise steam and put to sea until the next weekend. The guns were constantly firing and the coal dust made a fog on the mess decks.

One weekend we got leave to London but were recalled from all theatres and music halls – special trains ran us down to Weymouth and we gathered in the small hours of the morning on the pier to go off to our ships in Portland Harbour.

The Fleet sailed to Bantry Bay to continue our gunnery exercises. This was a completely desolate spot then but today it is a very busy deepwater port for giant oil tankers. A few sailors were allowed a short run ashore occasionally but they mostly got hopelessly drunk on ‘glasses of milk’ at one or other of the very few tiny dwellings on the hillsides.

Lion had 42 boilers and an Engine Room complement of 520. These were in four divisions of 130, and I was the ‘working hand’ of one under the Lieutenant- Commander (T) as there were not enough senior Engineer Officers aboard. One Sunday I had first got my division into some sort of order with no sign of (T) when through the bulkhead door adjoining came Admiral Bayly and all his staff – I was properly put through my paces but fortunately did not get disgraced!

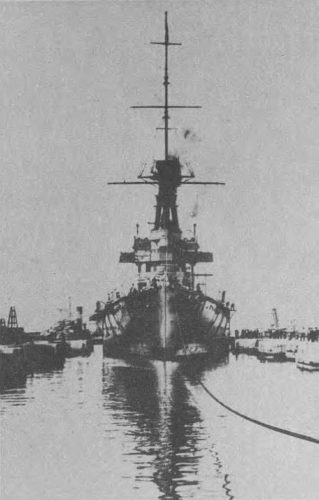

Early in 1913 I was appointed to the books of Victory for Australia building. My close companions were Clarrie Bridge and H. M. F. Robinson. We landed from our ships in Bantry Bay and caught a train that finally took us to Belfast and eventually to Glasgow. The grime of the city got the better of us so we rented a cottage at Helensburgh and lived there very happily while Australia was completing building. This was delayed as New Zealand’s armour failed on test, breaking up on impact of shells so she was given Australia’s, and new armour had to be made.

Another German scare arose later in the year and the Admiralty was most anxious for Australia to sail as soon as possible, however this emergency blew over and completion went on as usual. We were amused on trials at the then jealousy between Admiralty Departments – our ‘designed (?)’ horsepower was 44,000 and after measured mile tests, etc., we cracked on and got to 65,000 SHP! This was kept a close secret from the other Admiralty heads!

This additional power explains how the battle cruisers at the Battle of Jutland managed to get up to the speeds they achieved as their nominal SHP would only give speeds of 24 or 25 knots under the best conditions. These speeds were possible of course only with the best Welsh steaming coal – Australian coal is too full of ash, as trials in Australia later proved.

When we commissioned, King George V paid us a visit with the Prince of Wales, then a midshipman, and Australia’s High Commissioner, George Reid. The latter was a great favourite of the King’s and kept His Majesty very amused with his wisecracks.

Then followed the routine of the ship leading up to World War I. I served in the battlecruiser throughout the First World War with the exception of a nine week break at London Depot in February-April 1918. This period was marked by the series of accidents and lost chances which deprived our only capital ship of its glory, but this is another story.

Finally, in April 1918, after 5 years in the ship, I was transferred to Australia, travelling home in the fine old ship Marathon. I was appointed Engineer Officer to Williamstown Naval Depot and soon had on my hands the awful influenza epidemic which made manning such a problem, with war ended and ships returning and insufficient hands to raise steam. Also I had to report once a fortnight on the progress of setting up Flinders Naval Depot.