- Author

- Lind, L.J.

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 1974 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Soon after elevation to Flag Rank Rawson was placed on half pay. For the next two years he was able to enjoy a normal family life. His family consisted of two sons and a daughter and his home was at Southsea.

The three years that followed were pleasant. In late 1892 he joined the Signals Committee and worked hard on the revision of the signal system. This work was near complete when, on 4th May 1896, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief, Cape of Good Hope.

Admiral Rawson’s flag was hoisted in HMS Inflexible. The ships of the squadron were: HM Ships St. George, Philomel, Phoebe, Racoon, Blonde, Barrosa, Swallow, Magpie, Sparrow, Widgeon, Thrush, Alecto, Herald, Mosquito and Penelope. Four of these vessels later saw service on the Australia station.

The Cape command was anything but peaceful. Trouble had flared at Mombasa two months before Rawson’s arrival. The death of the Sultan Salim had sparked a war of succession. Rashid-bin-Salim, the legitimate heir, was opposed by a kinsman, Mubarak-bin-Rashid. The latter seized stocks of arms and ammunition and entrenched himself at Gongaro on the mainland.

Attempts to settle the problem diplomatically failed, so on 22nd July a force of 309 men from the St. George and Phoebe, supported by 70 Sudanese, advanced on Gazi. The expedition was commanded by Admiral Rawson.

The rebel forces withdrew from Gazi to Mweli, a stronger position on a hill. Another attempt was made to settle the issue peacefully but, when Mubarak repudiated the offer, Rawson ordered an assault on Mweli.

His force consisted of 220 sailors, 84 marines, 60 Sudanese, 50 Zanzibaris and 700 porters. Two seven pounder guns, four Maxim machine guns, and a number of rocket launchers provided fire support.

The 30 mile march from Gazi to Mweli was completed in five days. Rawson opened the attack on the fort with the seven pounders and rockets. This was followed up by a cautious advance under cover of Maxim fire.

The enemy held his fire until the assaulting force was at close range. Fortunately, the sailors from Phoebe forced an entry into the fort before the enemy could reload. Within two hours Mweli had fallen.

After destroying the fort, Rawson ordered his force to return to Gazi on the 21st. The capture of Mweli is described in the Admiral’s diary:

‘August 17: Pouring with rain and a cold wet day. A dismal seven mile march. Attacked Mweli at one o’clock. Rushed stockades, and got the place by 3 p.m.; two killed and five wounded. God guided and helped us. We ought to have lost 50 killed and wounded.’

Four days after the end of the Mweli Campaign the Sultan of Zanzibar died and a similar situation arose. The Prime Minister of Zanzibar, Sayed Khalid-bin-Burgash, seized the palace and refused to accept the legitimate claimant, Sayed Hamaud, as Sultan.

Thrush, Philomel and Sparrow were ordered to Zanzibar and anchored in the harbour within range of the Zanzibari Navy, the steam corvette Glasgow.

While sailors and marines were landed from the British ships, Khalid gathered a force of 1,200 and nine guns to resist the British.

The British held their attack until reinforcements arrived. Racoon arrived first to be followed two days later by St. George with Admiral Rawson.

Sharp at nine on the next morning the British ships opened fire on the palace. Immediately the Glasgow fired a broadside at the St. George. Racoon and Philomel turned their attention to the enemy ship. At point blank range they peppered her wooden sides and swept her deck. Glasgow was soon ablaze but re-opened fire. St. George then fired three salvos of six inch shells into the corvette. The gallant little vessel heeled over to starboard and slowly sank.

For 20 minutes the ships continued their bombardment of the palace, which was seen to be in ruins and burning fiercely. ‘Cease fire’ was sounded 37 minutes after the battle opened and two minutes later the magazines of the palace blew up. The Battle of Zanzibar was over.

The toll was 500 Zanzibaris killed and wounded and one British sailor seriously wounded.

It is interesting to note that Mrs. Rawson, her son and her daughter were aboard St. George and watched the entire action.

Rawson, like so many sailors of his time, had a surprising nicety of literary expression as this description of Zanzibar reveals:

‘Zanzibar can look very fair when seen in the morning light from the hills behind the city; it can look full of colour in the enriching darkening light of sunset, with its purpling roofs and copper-glowing foliage; it can look very beautiful and poetic in the full moonlight and the quiet of the tired city, hushed and still. And Zanzibar did look very beautiful that night, with the undimmed, clear moonshine, the white roofs whiter than by day, the harbour placid, the white ships resting on the blue water, the palace a blaze of light, and the garden of date-trees, with their still foliage.’

There was to be little respite for Rawson in his Cape Command. On 2nd January 1897, trouble flared on the west coast of the continent. A trade and diplomatic expedition to Benin City (modern day Biafra) was attacked on the Gwato Creek and almost annihilated by Benin tribesmen.

Thirteen days later Admiral Rawson was ordered by the Admiralty to mount a punitive expedition against Benin. The War Office asked what the expedition would cost and how long it would last. Rawson wired his reply: ‘Fifty thousand pounds and six weeks.’ The actual figures were thirty thousand pounds and four weeks.

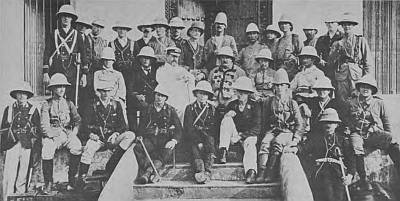

On the 20th January, Rawson arrived at Brass, the nearest anchorage to Benin. His ships were St. George, Phoebe, Alecto, Philomel, Widgeon and Barrosa. From the fleet he landed a force of 780 sailors and marines to which were added 280 native troops.

The campaign was the most arduous of Rawson’s career. Logistics were the key to success and once again he demonstrated his expertise in this field. The area around Benin was waterless and the temperature was close to 100 degrees.

A large force of carriers was assembled and half the punitive expedition was set to work making water depots along the route of advance.

By 12th February bases were established at Ceris and Ologbo. The enemy was present in the surrounding jungle and sporadic attacks were made on the advance guard.

The supply of water decreased as the force progressed so on the 16th Rawson split his force in half to form a Flying Column for the final assault.

On the evening of the 17th Rawson ordered a rocket barrage on the city. Next morning at 10.30 the Flying Column attacked. The enemy resisted strongly at first but the Maxim machine guns, which had been brought forward, broke the resistance.

Seven pounders joined the Maxims as the sailors pushed into the fortified city. At the entry of the main compound the natives rallied for a last charge. The sailors and marines broke the attack and Benin City fell.

Rawson, then aged fifty-five, had advanced on foot with his men. The ordeal was to remain with the Admiral for the remainder of his life. Arthritis set in in his hip-bone.

The Benin Campaign was Rawson’s last war. In May 1898 his command of the Cape ended. On his return to England he was placed on half pay for six months. Promotion to Vice-Admiral came on 19th March 1899, and with it command of the Channel Squadron. His flag was hoisted in HMS Majestic at Portsmouth.

Rawson retained this command until 16th April 1902, when he was succeeded by his old companion in arms of the assault on the Taku Forts, Rear Admiral A.K. Wilson, VC. He had already been informed of his appointment as Governor of New South Wales.

Promoted to Admiral, Rawson sailed for Australia on 9th April. He travelled by New York, San Francisco and Honolulu and arrived in Sydney on 26th May 1902.

The Rawsons – Sir Harry, his wife, daughter Alice and son Wyatt – soon settled into Government House, which was then located at Bellevue Hill, now Cranbrook School. It was their first visit to Australia and Sir Harry found the country stimulating.

Admiral Rawson soon became immersed in the exciting events of a country which had just become a nation. However, the Navy was his first love and he was delighted to contribute his ideas to the Commonwealth Fleet then being planned. Here are some of the ideas expressed by the Governor:

‘ . . . it will be said, a local Australian Navy will be useless. It would be produced without expert knowledge, the men and officers would not be properly trained, and the Squadron would be kept on shore under the orders of Australian politicians. We see no reason to believe in any such sinister prophecies. No doubt mistakes would be made, but these would be rectified by experience. We do not, of course, suggest that the Australian Navy should be autonomous or isolated. Just as the military forces are placed under a General of experience, so the Australian Navy would be placed under an Imperial Admiral, whose business it would be to carry the traditions of the British Navy into the new Service and to train the officers and crews. But even if the value of a local Australian Navy is admitted, it will be argued that that Australian Squadron should, at any rate, be under the immediate orders of the Imperial Government. So it perhaps ought to be in theory, in order to obtain the maximum of efficiency. In practice it had much better be under the Australian Government. They will pay the bill, and it is quite certain that they will take far more interest in, and spend much more money and trouble on, a force which is their very own. That they would in a time of emergency place it at the disposal of the Imperial Government is quite certain, and it is far better to rely upon such spontaneous help, as in the case of the Army, than to adopt any hard-and-fast rule . . . A fleet cannot be built in a day, but we see no reason why in the course of the next 10 years she might not have a fairly formidable squadron, a considerable number of officers, and besides the seamen and marines actually employed, a large reserve of men.’

The Admiral returned to England briefly in 1905 to be by the side of Lady Rawson, who had returned two months earlier because of ill-health. Lady Rawson improved later in the year and the family sailed for Australia in late November. Soon after leaving Suez Lady Rawson suffered a relapse and died at sea on 2nd December.

Rawson’s term of office as Governor of New South Wales ended on 24th March 1909. His departure produced long articles in the press and Sydney decorated her streets with farewell arches. An escort of Lancers, a guard of sailors and soldiers drawn from 2nd Australian Infantry followed the coach.

On his return to England the King honoured him with the GCMG. He was now 66 years of age and his health was not good. His last public appearance was a banquet at the Royal Naval Club on Trafalgar Day, 1910.

The long career of Admiral Sir Harry Rawson ended on 3rd November 1910. He was laid to rest at Bracknell Parish Churchyard on 8th November 1910.

A bronze memorial tablet in St. Paul’s Cathedral to his memory reads:

‘This is the happy warrior – this is he

Whom every man in arms would wish to be’