- Author

- Nicholls, Bob

- Subjects

- Colonial navies, History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2002 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Preposterous, you say. Not necessarily so.

It sometimes seems that the ‘Special Relationship’ between Great Britain (and thus, until quite recently, by extension, Australia) and the United States has existed forever. Certainly since the dark days of 1942, through to ‘All the way with LBJ’, to the present deployment of the ADF in the continuing war against terrorism. However, this felicitous state of affairs hasn’t always been so. First though, to set the scene.

Background

IT REALLY ALL STARTED WITH THE BRITISH. At the beginning of the 20th century the United States was isolated from the powerful alliance systems of Europe that had dictated the affairs of that continent for centuries. Given this state of affairs Great Britain and, naturally, her Empire, had to be considered as potentially hostile. American planners were therefore obliged to consider the prospect of war between the two countries.

In the United States system, colours were allocated to various nations, and the United Kingdom was assigned the code name RED. In turn Germany was BLACK, WHITE was France, ORANGE was Japan while the good guys, the US, were BLUE. (Subsets of the overall plan, certainly as far as the UK was concerned, were given ‘RED-ish colours such as SCARLET for Australia, GARNET for New Zealand, RUBY for India and CRIMSON for Canada.)

In war games conducted at the US National War College during the 1890s RED was always considered the aggressor, descending on the east coast of the continental US. Indeed, the British threat influenced the design of American capital ships, so that the United States Navy’s battle fleet was designed and built with a shallower-than-normal draught so that they could operate in shallow coastal waters in a defensive role. The fleet would therefore be at a disadvantage in operations in bluer, and thus deeper and more exposed, waters. So much for the Atlantic coast of the US.

As for the country’s Pacific coast, there doesn’t seem to have been any planning for its defence. Studies in the late 19th century of the defence of US possessions of the Philippines and the Hawaiian Islands concluded that they were indefensible. Elsewhere in the area, until the turn of the century there doesn’t seem to have been any attention paid to that ocean.

Enter Great Britain: During the 1890s, although France and Russia were still considered to be her primary potential enemies, the rise of Germany was being viewed with increasing unease in Whitehall. One area in which Germany was expanding was in the Pacific, and so plans to deal with that threat had to be made. One aspect was a closer relationship with Japan, who had long been trying to interest Britain in an anti- Russian pact. Anglo-Japanese talks culminated in an Agreement in 1902. The negotiations were conducted in secret and without reference to a newly-Federated Australia, which was introducing an Immigration Restriction Bill, aimed primarily at the exclusion of Japanese from the country. The accord was developed further and by the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, which completely altered the balance of power in the Pacific, Japanese influence in the area was greatly expanded.

To make matters worse from the United States point of view, the conclusion of a more specific Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1905 introduced a clause which bound the two signatories to come to the aid of each other should one of them become involved in a war with any other power.

Finally, anti-Japanese sentiments in California intensified during 1905, leading to serious rioting in San Francisco and other centres in 1907.

The situation was so threatening that the United States decided to assemble a fleet of battleships for ‘despatch to the Orient as soon as possible’.

Along the way the assemblage turned into a round the world cruise, a voyage that would be expanded later to include visits to New Zealand and Australia.

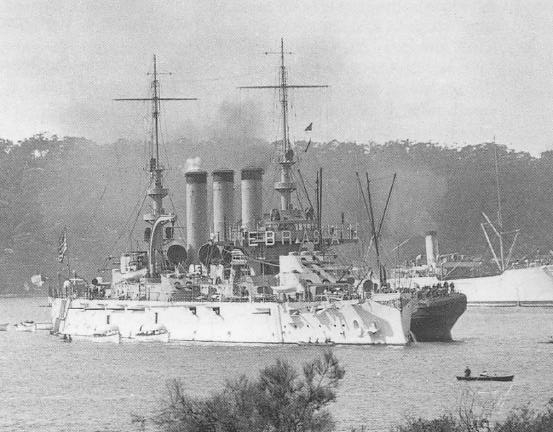

The adventures of this fleet, which came to be called ‘The Great White Fleet’ because of the colour of its hulls (at a time when every other navy of repute had turned to grey for its livery) do not concern us here. (See the end of Part II of this article for a bibliography of books describing its voyage.) Rather, our interest concerns one of the collateral results of its visit to New Zealand and Australia.