- Author

- Nicholls, Bob

- Subjects

- Colonial navies, History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2002 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The initial fleet commander was Rear Admiral Charles S Sperry. He had formerly been President of the War College and thus could be considered to be thoroughly conversant with planning matters. An intelligence team led by Major Dion Williams USMC was embarked. After the fleet had visited Japan the admiral became ‘stubbornly confident that a row with Japan was imminent’. He therefore ordered that war plans be made for the capture of New Zealand and Australian ports. These plans were based on the premise that they were for use ‘in case of a war between the United Sates and Great Britain or a war involving those countries’. This implies that the planners had in mind a war with Japan in which Great Britain complied with the provisions of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and was on Japan’s side.

Today this scenario may seem unlikely, but perceptions were different almost a century ago and in any case the admiral had spoken. So, despite overwhelming hospitality shown to the United States Navy in both Dominions, the visitor’s intelligence teams were busy beavering away to produce their plans.

This section will describe the plans for attacking Auckland and Sydney; Melbourne and Western Australia will be covered in Part II.

The Auckland Attack Plan

Capturing Auckland would provide the United States with an advanced base preparatory to attacking Sydney. Waitemata Harbour, Auckland’s principal harbour, was deemed ‘easy of defence’ but it was noted that there were no coastal artillery batteries, a deficiency ‘which was bitterly commented on by the British and New Zealand officers with whom our Intelligence officers talked at Auckland’. The report concluded that if ever the main harbour’s defences were improved Auckland would still have a weak point in the fact that ‘Manukau Harbor, on the western side of the island and directly opposite Auckland Harbor, offers a ready means of attacking the city from the rear’.

The planned position of a minefield to protect the approach to Waitemata Harbour was noted. The mines themselves were in short supply and those that were held were of an obsolete model.

The report listed the 1908 defence Order of Battle in considerable detail, noting that the bulk of the forces were volunteers, whose efficiency was ‘about up to the general average of the National Guardsmen in the United States, though not so well fitted out with field equipage and transportation’. Furthermore they were so widely scattered geographically that the entire force would never have to be dealt with at the same time.

So much for the Kiwis.

The Sydney Attack Plan

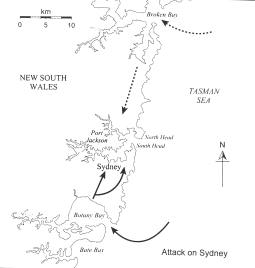

After the capture of Auckland, Sydney was next on the list. In a comprehensive report, which included a detailed eight-page summary of the defences of Port Jackson, Sydney was described as the principal goal: ‘A fortified base and coaling station for the British Navy, its attack and capture . . . would be a severe blow to the British in these waters’ and would afford the invader ‘the most desirable base for further operations both on land and at sea in and about Australia.’

There were, however, problems. Port Jackson was ‘comparatively strong and the entrance readily mined’. And, unlike New Zealand, there was a strong force available for its defence.

The American assessment concluded that a direct frontal assault would be difficult. It did, however, note that one of the principal disadvantages for the defenders was that ‘the city was practically directly on the sea coast, the center of the business portion of the city being but three sea miles from the open sea front’. This meant that ‘a fleet could lie off the entrance to the harbor and shell the whole city at effective ranges’. Shades of mid-1942.

Botany Bay, just ten miles south from the entrance to Port Jackson, attracted attention as a possible area for a flanking attack. Broken Bay was also considered but, according to the intelligence team, ‘such an attack would scarcely be advisable owing to the difficult ground lying between Broken Bay and Port Jackson’.

Laying these practicalities aside, the team looked at the broader picture and concluded that no operations with the capture of Sydney in mind should be undertaken until command of the sea had been assured. They concluded that ‘an examination of their defences (here they were referring to Sydney) and forces provided for these defences accentuate [sic] the firm reliance placed by all British subjects on the British Navy.’