- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2018 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

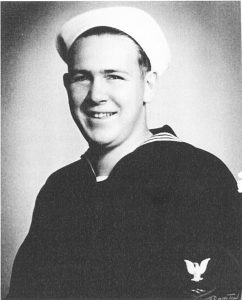

A long standing member of our Society, David Mattiske, was a friend of John Adams who died early in 2017. David presented us with a self-published memoir of John Adams giving an account of his USN service. The following summary provides some indication of one man’s extraordinary contribution to the war in the Pacific.

Joining the Navy

John Ottomar Adams’s father had served in the Marine Corps during WWI so as a 17 year old he went to their recruiting office in Camden, New Jersey, to be told he did not meet the height requirements and it was suggested he try the Navy. A short time later, on 8 November 1940 he enlisted in the US Naval Reserve and service life began with a four month training course at a US Radio Training School at the small town of Noroton, Connecticut.

Starting pay as a Recruit was $21 per month, and following graduation came promotion to Radioman Third Class with a pay rise to $115 per month. On graduation the whole class boarded a train and crossed the country to California where they were to join ships at the San Diego Naval Base.

John’s first ship, the destroyer USS Henley (DD–391), was undergoing a refit at the Bremerton Navy Yard in Washington State when he joined her in March 1941. She was a Bagley-class destroyer first commissioned in August 1937. After refit Henley became leader of the 7th Destroyer Division, providing support to the carrier group then operating out of Pearl Harbor.

Pearl Harbor

Following routine exercises which included acting as plane guard and conducting live firings, most of the fleet, including Henley, made for Pearl Harbor, finding secure berths on Friday 5 December 1941 and looking forward to shore leave. Two days later a leisurely Sunday morning breakfast was interrupted when General Quarters (Action Stations) was sounded as Japanese aircraft started their devastating bombing raid.

John proceeded to his action station as first shell loader on No 3 Gun, a 5-inch 38 calibre open mounting, on the after deck house. With all hatches and doors dogged down it took him about ten minutes to arrive, by which time the guns were firing, not too effectively, at retreating waves of aircraft. Henley must have been in a good state of readiness as she was credited with being one of the first ships to fire at the enemy aircraft. When the action was over the destroyers put to sea and it was when they returned to port several days later that they were able to witness the devastation caused by this unprovoked attack. Welcome to the Second World War. It may be noteworthy that the author says that during his time in the Pacific he did not don anti-flash gear, the normal rig at action being a short sleeved shirt and blue jeans with a gob style soft cap.

Into the Pacific

Henley next had a relatively quiet time escorting convoys taking supplies across the Pacific to such places as American Samoa, the New Hebrides and New Caledonia. Following the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 a tanker, USS Neosho,had been bombed and Henley was ordered to render assistance. After finding the ship, over 120 survivors were taken off (many were from the destroyer USS Sims which had been sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea) and then the decision was made to scuttle the tanker. The first torpedo failed to detonate and a second did explode but caused little damage so she was sunk by gunfire. The survivors were taken to Brisbane but two died during the transit and the ship’s company witnessed their first burials at sea. At this stage no one from Henley had ever visited Australia. However it did not take long for them to settle in, and when making his way down Queen Street John came upon the newspaper offices of the Courier Mail where he was looking for past copies with commentary on the Pacific war. He was served by the attractive young Doris Lydia Lambe, later to become Mrs Adams.

The time in Brisbane was mainly spent on training exercises with Australian warships and on convoy work up and down the east coast. When operating off North Queensland they were sometimes allowed ashore on the beautiful Whitsunday Islands, which at this time were virtually uninhabited, other than for the Aboriginal settlement at Palm Island.

In July 1942 Henley was ordered to join with HMA Ships Australia, Canberra and Hobart and proceed to Wellington, New Zealand to escort a convoy taking the 1st US Marine Division to the Solomon Islands on the first step to regain control from the Japanese in the Pacific. They departed Wellington on 22 July and first called at the Fijian island of Koru where practice landings were made before trying the real thing on beachheads at Guadalcanal and Tulagi. For a short period in mid-1942 a US Marine regiment was based at Koru to assist with the preparation of troops before sending them forward to the Solomons.

On their next supply run from Noumea to the Solomons they were called upon to conduct shore bombardment at Tulagi and Tanambogo Island where the Marines had encountered strong resistance. The ships encountered little bother from shore fire but air attacks were becoming more frequent where three US destroyers were damaged and one, USS Jarvis, was subsequently sunk by a Japanese submarine when en route to Noumea.

Battle of Savo Island

On the fateful night of 8 August the Task Force Commander, Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley1, divided his ships into three separate groups. The Southern Group comprised the cruisers Australia, Canberra and USS Chicago and the destroyers Henley and US Ships Bagley and Patterson.Two other radar-fitted destroyers, US Ships Blue and Ralph Talbot, patrolled the channel at the entrance to the sound between Cape Esperance and Savo Island.

That same evening the Japanese commander, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa with his cruiser squadron steamed straight past and unseen by the Blue/Ralph Talbotpicket.

At about 1.30 in the morning of 9 August the Japanese cruisers opened fire with their targets eerily illuminated by flares dropped from float planes. When the Japanese turned for home, fearful of daylight carrier air attacks, three Allied cruisers, including Canberra, had been sunk and several destroyers were damaged. The Japanese suffered no losses in the actual engagement but on the return to New Britain the cruiser Kakowas sunk by the submarine USS S-44.

A Near Miss

The remainder of their time was spent protecting convoys between Noumea and the Solomons. During one of these convoys the commander of the destroyer squadron who normally flew his pennant in Henley transferred to Blue. Now senior ship, Blue led the return convoy to the Solomons. After dark on 22 August, Blue suddenly came to a dead stop in the water after having been torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer. When survivors were taken off Blue was scuttled. If the destroyer commander had not transferred his pennant it may well have been Henley and many of her crew that would not be around to tell the tale.

Eventually after the battle for Guadalcanal reached its climax the destroyers Henley and USS Helm were re-assigned to Rear Admiral Crutchley’s new Task Force guarding the southeast approaches to New Guinea. His forces were divided into two groups with one continuously patrolling at sea and the other based at an anchorage at Challenger Bay on Palm Island. These two groups would alternate every ten days or so with occasional visits for supplies to nearby Townsville and the more distant Brisbane.

Patrol Torpedo Boats

By this time John had been promoted to Radioman First Class (Petty Officer) and it was then that a secret document went missing from the radio room. A subsequent investigation found that in all probability the document had inadvertently been incinerated with classified waste. But someone was to blame and John was demoted to Radioman Second Class. There is an unwritten rule in the USN that if a man is demoted he is entitled to seek a transfer to another assignment when this becomes available and it is invariably approved.

In December 1942 a USN Patrol Boat Base was established in Milne Bay, initially comprising four boats. The Seabees had been busy at Kana Kope at the south eastern end of Milne Bay. In a region without roads an area about the size of a football pitch had been cleared from the jungle where a small base had been constructed with wharves, workshops, mess hall and radio room. Small amounts of ammunition and fuel were held here and most importantly there was a generator powering a refrigerator which held perishable food.

When a posting became available with the PT Squadron he was put ashore at Townsville and took the train to Cairns. Here over a few weeks a small US contingent was assembled and taken by an RAN corvette to Milne Bay.

He was surprised how small PT Boats were, at about 72 feet (22 m) long and built of marine plywood. They were fitted with three V-16 Packard supercharged petrol engines. On trials in lightship condition and without silencers, speeds of 60 knots had been achieved. They were originally fitted with 4 x Mk 8 torpedos launched from 21 inch tubes and several 0.30 calibre machine guns, subsequently upgraded to 0.50 calibre. They also could take up to eight depth charges. Depending upon weapons fitted, they had a crew of two or three officers and from 8 to 12 men.

They were squeezed like sardines into these small flat-bottomed boats which were extremely hard riding and uncomfortable even in the slightest seas. With the weight of a heavily armed boat and extensive marine growth in tropical waters these boats rarely achieved a top speed of 40 knots.

The routine for PT operations was regular patrols of about 12 hours duration, normally leaving their moorings just before dusk and proceeding to assigned areas at a cruising speed of about 20 knots, then cruise at slow speed 2000 to 3000 yards offshore looking and listening for suspicious activity. If this occurred they would open up with the 0.50 machine guns. When the boats first arrived in New Guinea attacks were usually against unprotected Japanese landing craft and these were easy pickings. Because of their shallow draught the favoured Daihatsu-class landing craft were virtually immune to torpedo attacks.

The Japanese learned quickly and started fitting armour plating and arming their boats with twin machine guns which could effectively return fire.

John says: On one mission near Buna we were hit by shore fire but luckily the shell went right through one side of the bow and out the other. Under escort we were able to limp home for repairs. On another occasion on night patrol off New Britain where we had been sent to investigate enemy activity we were suddenly illuminated by a searchlight and then machine guns opened up on us. We had disturbed a Japanese destroyer who, not knowing how many of us were around, took off at high speed; we gave chase but soon lost him.

The camaraderie of the PT Squadron made for very happy days. One of their number had discovered that torpedo fuel is almost pure alcohol and this mixed with icy cold grapefruit juice makes an excellent concoction of which James Bond would have been proud. But all good things have to come to an end and it was time to return to the big ship navy.

Loss of USS Henley

Although John had left Henley in early 1943 she remained an important part of his life. Late in September 1943 Australian troops had established a beachhead at Finschhafen in New Guinea. With two other US destroyers, Henley formed part of a protective screen where they were attacked by Japanese torpedo bombers, three of which were shot down. In the same area, while conducting a defensive sweep on 3 October Henley was critically damaged by torpedoes fired by the submarine RO-108. Before she sank the crew were rescued by her companion destroyers but 15 officers and men did not escape.

Admirals’ Staff

In early 1944 he was posted to the headquarters staff of the Commander Southwest Pacific. This was in the AMP Building in central Brisbane with General Macarthur occupying the 10th floor and Vice Admiral Kinkaid the 9th floor. Shortly after arrival he developed a very high fever and was hospitalised. This was thought to be malaria but after several weeks of treatment he was diagnosed with dengue fever. After recovery he was involved in the assault on Humboldt Bay in Dutch New Guinea, where the important border town of Hollandia is situated. The staff was flown to Manus Island to board the purpose-built flagship of the 7th fleet, USS Wasatch. This was an excellent career move as he had now been promoted to Chief Radioman.

In the early hours of 22 April 1944 the initial bombardment commenced and after overcoming slight resistance two beachheads were established and, most importantly, the Hollandia airfield was captured four days later. The Seabees lost no time in constructing a shore headquarters for Macarthur and Kinkaid where plans were finalised for the great push for a triumphal return to the Philippines. In this remote region an immense fleet of about 700 ships was assembled, ranging from aircraft carriers and battleships to submarines plus minor war vessels and numerous transports. All this was coordinated from the communications centre of the flagship Wasatch.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

John Adams tells us that Wasatch departed from Humboldt Bay towards dusk. The next morning when he went on deck, all around were ships stretching to the horizon. Because of slower ships carrying much needed supplies the speed was no more than 10 knots. On the afternoon of 17 October minesweepers were detached to clear the approaches to the Gulf and this continued for several days until a bombardment of 16-inch battleships, 8-inch cruisers and 5-inch destroyers commenced on the morning of 20 October. Finally troops landed and with light opposition secured the beachheads and cleared the immediate hinterland. Later the same day Macarthur and his selected staff staged their beach landing and made his famous ‘People of the Philippines, I have returned’ speech.

This battle of the titans was the last throw of the dice for the Japanese Navy which afterwards was unable to assemble a coordinated fleet. With the end of the war now in sight John managed to wangle a posting back to Brisbane to help with the post-war closure of the old headquarters.

Closing the Shop

He returned to Brisbane by plane, arriving on 28 April 1945. Just over a week later, on 5 May, Doris and he were married with very few on his side of the church. After a honeymoon using his new brother-in-law’s home at Redcliffe it was knuckling down to the job in hand, with the Brisbane office eventually closing on 11 January 1946. His final job was to assist in valuing equipment ready for disposal at knock-down prices as war surplus.

John returned to the US with his new bride and received his discharge from military duty on 13 February 1946. They then met with his family whom he had not seen since leaving for naval radio school in October 1940. After service life he decided to seek entrance to university to study electrical engineering. In June 1946 he sat the entrance examination for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and commenced studies.

For older students, many of whom were married ex-servicemen, MIT provided basic married accommodation which suited them. Doris was also able to obtain employment within the campus. After graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering he worked for a while with General Electric at a factory in Boston. But the call from Down Under was strong and in 1951 they decided to return to their new homeland.

Summary

John Ottomar Adams had a remarkable wartime naval career, first serving in a gun crew at the Battle of Pearl Harbor and then extending across the Pacific to the aftermath of the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Battle of the Solomons, patrol boat engagements in New Guinea and finally a front row seat at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. This is a privilege enjoyed by very few and there are not many who could match his extensive wartime service, keeping him away from home for well over five years.

While in Henley she had twice served in a Task Force under the command of the Australian Fleet Commander, Rear Admiral Crutchley, who mainly flew his flag in Australia. It was here that John became familiar with the RAN and in particular Australia and Canberra and her replacement HMAS Shropshire. In later life, with no other US Navy Associations in Queensland, John joined the Gold Coast Branch of the HMAS Canberra/Shropshire Association and for many years served as secretary. Aged 94, John died in January 2017, and is survived by his second wife Dawn, their two children and three grandchildren.

Note:

- 1. Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley DSC, VC (later Admiral Sir Victor) was a Royal Naval WWI hero who was lent to the RAN as Commander of the Australian Squadron from June 1942 to June 1944.