- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - post WWII, Post WWII, Korean War

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

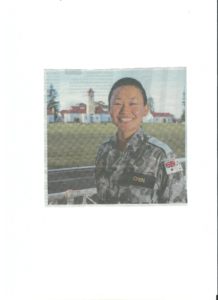

By MIDN Li-Chun Chen RAN

Born in Taipei, Taiwan, Chen grew up in Melbourne where they developed a love of learning with particular interests in science and philosophy. The younger of two siblings, their older sister was always a great role model, embodying the benefits of persistence and consistency.

With varied interests, Chen studied multiple degrees at university, graduating with a Bachelor of Business (Sport Management) and a Graduate Certificate in Regional Sustainable Development. Prior to joining the RAN, Chen worked in retail management and the finance industry.

Chen entered the Navy through the New Entry Officer Course (NEOC 66) and found that Navy welcomes trainees, regardless of gender, cultural background or ethnicity, saying: ‘I am non-binary, and for me, the RAN has been such an accepting workplace. Being part of the LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual, plus) community does not constrict my work in any way. My desire is to continue seeing diversity increasing in the Navy. The ADF should be a microcosm of society.’

MIDN Chen received two awards at the NEOC graduation: the Australian Naval Institute – the Creswell Cup, awarded to the graduate who demonstrates the most outstanding performance in leadership and dedication to Defence values; and the Naval Historical Society Prize awarded for the best researched naval history essay.

Always intrigued by aviation, the multifaceted role as a Maritime Aviation Warfare Officer appealed to them and the prospect of sunrises and sunsets in a helicopter sealed the deal. MIDN Chen enjoys reading, eating, hiking and watching animations.

Background

The Korean War (1950–1953) arose in the aftermath of World War II, with Allied Nations being unprepared to enter another conflict. Divided along the 38th parallel, with Soviet forces in the north and United States (US) forces in the south, the Korean War was the first major conflict to confront the newly formed United Nations (UN). The US’s lack of interest in Korea, despite internal division of government, led to minimal protection of the south, enabling the Communist north to invade. Korea exemplifies the potential consequences of wavering military preparedness in peacetimes and its devastating flow-on effects.

Aim

As tensions arise in the South China Sea, Korea serves as a focal lens for the consequences of Australia’s high dependency on Allied nations but also highlights the potential of internal joint force operations as a force multiplier. This essay will discuss how constant strategic and operational preparedness are integral to the future success of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and the Royal Australian Navy (RAN).

Scope

This paper will not recount the details of the Korean War but, rather, highlight Australia’s involvement and discuss parallels between the current ADF and the military in the lead-up to the war. Particular focuses will include Australia’s historical and persistent reliance on other nations; the efficacy of joint naval and air power in Korea, and how the ADF should utilise joint service command to further capability, enabling the ADF and RAN, to be a proactive, rather than reactive force.

Post-WW2 Demobilisation

Demobilisation of the Australian military at the end of WWII saw a significant decrease in personnel and capability, which was detrimental to Australia’s participation in Korea. From a force of nearly 600,000, less than eleven months after the Japanese surrendered, nearly 80% had been discharged (James 2009). With the foresight that many members would be seeking timely discharge, the Australian Government began planning (as early as 1942) the demobilisation process for personnel and equipment (Butlin 1977). However, prior to the war’s end, the Commonwealth Disposals Commission began urging the three services to audit their ‘excess and surplus’ equipment. The pre-planned demobilisation scheme, whilst illustrating the Government’s optimism about an ending to the war, also illustrates short-sightedness. This is substantiated by backlash from Army Commander-in-Chief, Thomas Blamey, who argued that Australia may still require equipment for operations after defeating Germany (Butlin 1977). The advanced demobilisation of the armed forces suggests the Government’s belief that Australia would not, in the near future, be involved in any other wars. Furthermore, the mass sale (and loss) of military equipment (Butlin 1977) cemented Australia’s reliance on other Allied Nations due to diminished capability. The Government’s focus on strategically maintaining relationships for defence, rather than building upon its own defence force, has had major ramifications, the first of which was Australia’s involvement in the Korean War.

Australia’s Strategic Involvement

Australia’s involvement in the Korean War was entirely strategic and rested on Australia’s reliance on allied powers for security. Little attention was given to Korea after WWII and maintenance of peace across the 38th parallel was seen as a US responsibility. However, whether due to arrogance or simply decreased fear of threat, the US withdrew its army from Korea in 1949, leaving only a few hundred men (Evans 2012). This, coupled with the January 1950 US Secretary of State’s speech (which failed to mention Korea as part of the US defensive perimeter (Matray 2002), is speculated to have incentivised North Korea’s invasion of the south on 25th June 1950. Due to having reduced armed forces, Australia initially only committed the RAAF 77 Squadron and HMA Ships Shoalhaven and Bataan, both of which were already operating in Japan as part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (Edwards 2015). Following demobilisation, only in 1948 did Australia create a standing army, consisting mainly of three infantry battalions (the Royal Australian Regiment,) formed from WWII units (Edwards 2015). Commitment of ground forces were political and diplomatic manoeuvres (Edward 2015), highlighted at the commencement of the Korean War. It was widely publicised that Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was hesitant to commit troops, following the lead from Britain. However, Percy Spender, the Minister for External Affairs, was keen to secure the ‘Pacific-Pact’, a security treaty between the US and Australia and New Zealand, later named ANZUS (Cotton 2015). A mere hour prior to Britain announcing their support in Korea, Australia announced its commitment of the 3rd Battalion the Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR). This signified independent support for the US and laid groundwork for the security treaty, in a strategy known as ‘forward defence’ (Stephens 1999). This commitment later extended beyond 3 RAR to include all three RAR battalions and ultimately led to 339 casualties, over 1200 wounded and 29 prisoners of war (Evans 2012). Currently operating in similar, post-war, peacetime conditions, it would be highly beneficial for the ADF to retain the sense of wartime-like urgency to ensure constant operational readiness.

Korea was not the cornerstone of the ANZUS treaty, however, it is recognised as ‘a vitally important element’ (Cotton 2015) in securing the relationship between Australia and the US that exists to this day (Edwards 2015). Post WWII, Australia did not have the capability to maintain peace in the Pacific without assistance and thus, the ANZUS Treaty was strategically practical. However, since then, little has been done to bolster Australian defence to reduce foreign reliance. Australia’s geographical proximity to China means trade route safety in the South China Sea will have a large correlation with the preparedness and capability of the RAN. Regardless of the practicality of inter-military operations in conflict situations, strategic reliance on other militaries fails to place Australia’s own interest at the forefront of planning. This has resulted in a dependent military, but also in a reactive military that lags in striving for cutting-edge advancement, reliant on the US for support. Recent and unexpected conflicts, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, underpin the importance of constant operational readiness. Concurrent to this conflict, Australia has an 18-month taskforce discussing where to base nuclear submarines, showcasing a severe lack of urgency. Furthermore, there is a minimum fourteen-year gap between when nuclear submarines will be completed (late 2030s) and when the current Collins Class are set to retire (2026) (Greene 2016). This highlights the lack of urgency in planning, how the ADF settles for ad hoc solutions and also illuminates how cutting-edge, new technologies are not a priority. With the threat of China and unrest in the South China Sea growing, these actions undermine the Government’s claims of operational readiness and military prowess.

Technology and Joint Capability

Australia is acknowledged for having a small yet highly trained military, which could be more effective if not restricted by outdated strategies and technology. Though limited in personnel, the contributions of Australia in the Korean War are recognised as fundamental in maintaining the 38th Parallel (Evans 2012). General MacArthur, who led the UN forces, described 77 Squadron as ‘first class’ (Evans 2012); and Australian P-51 Mustangs were the only regionally appropriate and available aircraft at the onset of war. The RAAF were responsible for ground attacks and in defending against initial air attacks whilst the US remodelled their planes to be regionally appropriate. However, despite the skill and courage of Australian fighters, introduction of MiG-15 jets from the enemy meant that the RAAF suffered and ‘could hardly say [they] played a major role in deterring MiGs….[due to] possessing an inferior fighter’ (Evans 2012). This underpins the fact that the ADF could achieve greater excellence if not limited by outdated equipment.

Nevertheless, the Korean War also exemplified the success that can be achieved by forward-planning, illustrated by the successes of the aircraft carrier, HMAS Sydney. Though the RAN’s contributions extended further than Sydney, her deployment made Australia the third nation to employ naval air-combat operations after WWII (Evans 2012). In a mere three months, Sydney’s aircrafts had flown 2366 sorties, showcasing Australia’s operational excellence (Evans 2012). Chinese Premier, Mao Zedong, even reflected that ‘the important reason we [Communists] cannot win decisive victory in Korea is our lack of naval strength’ (Evans 2012), highlighting how bolstering the RAN is essential in ensuring Australia’s safety and military strength.

The joint capability of sea and air proved effective in Korea and illuminates the benefits of a joint-service approach to defence. However, as discussed in detail by Stevens (1999), ideological differences have resulted in the RAAF and RAN performing differing levels of maritime operations, reducing aviation efficacy. Historically, inconsistent operational management led to RAAF fighters revealing RAN locations during stealth missions, illustrating the catastrophic outcomes of inter-service miscommunications (Stephens 1999). Defence’s inability to either separate or fully merge the roles of the RAAF and RAN persist today with the 2016 White Paper placing responsibility on both RAN aircraft and RAAF P-8A Poseidons for maritime surveillance (Department of Defence 2016). Joint naval and aviation operations ‘could increase the effectiveness of a cruiser by at least ten times’ (Stephens 1999), yet there remains separation in aviation across all services. The divide between services begins ab initio with even basic military skills being taught differently across services. The effects are two-fold: additional funds are used to separately manage training programs; and again, in when members require ad hoc operational/communication training for cohesive tri-service operations. Efforts to unite services (such as replacing individual service values with joint values), fail to disseminate tactically to ground level. Benefits of joint capability as a force multiplier were clearly demonstrated in Korea, however, efforts to capitalise on this are lacking. A united armed force, or even improved unity between services, may streamline resources and maximise joint capability benefits.

Conclusion

Australia’s participation in the Korean War is a useful lens through which to develop the current ADF and RAN. Naval contributions were acknowledged as fundamental in halting invasions, thus highlighting the importance of a capable RAN. However, systemic issues stemming from the ADF have hindered force optimisation. Over-reliance on foreign militaries and laggard planning have resulted in sluggish growth. Furthermore, conservative strategies have stunted innovation and hindered the potential of capable personnel. The force multiplier benefits of joint naval and aviation operations in Korea suggest increased unity of the services may optimise future capability and streamline funding.

Bibliography

Bicker, L. 2021, South Korea: End to Korean War agreed to in principle, BBC News, 13 December, accessed 5 April 2022, <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-59632727>.

Butlin, S.J. & Schedvin, C.B. 1977, War Economy, 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 4 – Civil, Australian War Memorial, e-book, accessed 6 April 2022, <https://www.awm.gov.au/ collection /C1417270>.

Cotton, J. 2015, Australia and Korea: 65 years after the Korean War, Australian Institute of International Affairs, accessed 02 April 2022, <Australia and Korea: 65 Years After the Korean War – Australian Institute of International Affairs – Australian Institute of International Affairs>.

Department of Defence 2016, 2016 Defence White Paper, Australian Government, Department of Defence, Canberra, accessed 02 April 2022, <http://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper/Docs/2016-Defence-White-Paper.pdf>.

Edwards, P. 2015, From Hiroshima to Vietnam, Wartime Spring 2015, issue 72, p. 13-19.

Evans, B. 2012, Out in the Cold: Australia’s Involvement in the Korean War 1950–53, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra.

James, K. 2009, Wartime Magazine – Issue 45: Soldiers to citizens, media release, accessed 05 April 2022, <https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/45/article>.

Matray, J.I. 2002, ‘Dean Acheson’s Press Club Speech Re-examined’, Journal of Conflict Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1. Accessed: 5 April 2022, <https://journals. lib.unb.ca/index.php/JCS/article/view/366>.

Stevens, D. 1999, Prospects for Maritime Aviation in the twenty first Century, Department of Defence (Navy), Canberra.