- Author

- Kennedy, David

- Subjects

- RAN operations, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Rushcutter (Shores establishment)

- Publication

- March 2005 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The British Officer-in-Charge of Australia’s anti-submarine training establishment warned Navy chiefs, four months before Japanese midget submarines attacked Sydney Harbour in May 1942, that the defences against such a raid were deficient.

‘I am not satisfied that an efficient I/L (indicator loop) Watchkeeping scheme is being carried out at South Head’. He requested that: ‘instructions be issued for a watchkeeping scheme..’ that included: ‘one officer is always to be in the Loop Control Room’ and ‘be relieved for meals by a stand-by officer.’ At night ‘the Duty Loop Watchkeeping Officer may sleep dressed in the compartment above the Loop Control Room,’ he wrote. ‘Two ratings are always to be on watch. Only one rating may leave the control room to attend to motor generators etc.’

Thus wrote Acting-Commander Harvey Newcomb in a formal letter to the Commodore-in-Charge, Sydney, Gerard Muirhead-Gould RN. Newcombe was a Royal Navy officer sent from UK in late 1938 to start up a little-known Anti-Submarine establishment at Edgecliff, on Sydney Harbour, as war clouds gathered and the British Empire prepared to defend important Commonwealth ports against the threat of U-Boat attack. He was appointed Acting-Commander before leaving to head the Sydney facility, which became HMAS Rushcutter. The letter was written to stress the gravity of the wartime situation six weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, which included attack by five midget submarines. Three of these submarines were sunk by US warships.

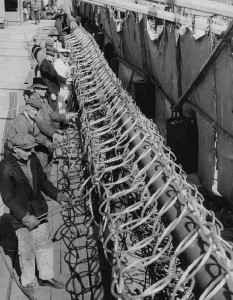

By 1942 the Sydney Harbour defences included six indicator loops – cables up to thousands of metres long laid on the seabed to record electronically on shore the passage of a submarine or surface ship over them – covering a wide arc outside the Heads. There was another loop between the Heads and yet another further in. These loops, controlled by a facility at South Head, were backed up by a nearly completed anti-submarine and torpedo net boom that was opened and closed by tenders (auxiliary craft) to let vessels through between openings off Georges Head, and Green Point on the south shore.

Japanese spotter plane

On May 30 1942, three Japanese midget submarines also attacked a Royal Navy fleet anchorage at Diego Suarez in Madagascar, off East Africa, damaging the battleship HMS Ramillies and sinking a tanker (British Loyalty), a day after a reconnaissance flight by an enemy aircraft. On the same day an unidentified aircraft, actually a spotter plane from a Japanese mother submarine, circled the Sydney Man-of-War anchorage near the Harbour Bridge. An almost identical attack was made on the night of 31 May on Allied shipping in Sydney Harbour, which contained at that time the heavy cruiser USS Chicago, the destroyer USS Perkins, the heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra, the light cruiser HMAS Adelaide, and armed merchant cruisers HMA Ships Kanimbla and Westralia.

‘Suspicious object’

Sunday evening, 31 May 1942, was dark and cloudy with the first layers of detection being the outer and inner indicator loops at the Heads, although the first mentioned was out of action. A flotilla of five large Japanese submarines off Broken Bay released three midget submarines. The signature of an inward crossing was recorded on an indicator loop at 2000. It was made by Midget No. 27 (from I-27) but at the time, owing to ferry and other traffic over the loops, its significance was not recognised. Fifteen minutes later a Maritime Services Board nightwatchman sighted a suspicious object caught in the anti-submarine net and investigated it in a skiff, before reporting it to the patrol boat NAP Yarroma at about 2130. Yarroma signalled to Sydney’s Naval Headquarters on Garden Island. ‘Object is submarine. Request permission to open fire’. Five minutes later demolition charges in Midget No. 27 were fired by its crew, destroying the craft. Meanwhile, at 2148, another inward crossing was recorded on theindicator loop (later identified as Midget No. 28 from I-24) again taken as of no special significance.

A General Alarm was sounded at 2227 for the ‘suspicious object’ and at 2236 by the Naval Officer-in-Charge (Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould RN) for the confirmed submarine. At about 2250, Chicago, preparing to sail, sighted a submarine periscope (apparently Midget No. 28) about 500 yards off, illuminating it with her searchlights and opening fire with pom-pom tracer fire. During this firing Midget No. 22 (from I-22) was entering the Heads and her conning tower was spotted by the NAP Lauriana, on patrol in the loop area with NAP Yandra, which tried to ram the midget then depth-charged it. The submarine was not seen after the explosions. At 2330 the accommodation vessel HMAS Kuttabul (a converted harbour ferry) alongside the east shore of Garden Island was blown up by one of two torpedoes fired at Chicago by Midget No. 28, from the direction of Bradley’s Head.

An indicator loop reading at 0158 was later judged to be Midget No. 28 leaving the harbour.  The last reading at 0301 was presumed to be Midget No. 22 making a belated entry after recovering from the depth charge battering she had received from NAP Yandra four hours earlier. Midget No. 22 was sunk in Taylor Bay at 0500 after depth charging by Yarroma and her consorts NAPs Steady Hour and Sea Mist.

The last reading at 0301 was presumed to be Midget No. 22 making a belated entry after recovering from the depth charge battering she had received from NAP Yandra four hours earlier. Midget No. 22 was sunk in Taylor Bay at 0500 after depth charging by Yarroma and her consorts NAPs Steady Hour and Sea Mist.

Commodore Allen Dollard, RAN Retd, a lieutenant in HMAS Australia at sea on the night of the attack, says the flaws in the harbour defence had not been suspected, generally because of the secrecy of the anti-submarine operations.

Although the anti-submarine boom had not yet been fully completed, with gaps at each end, it had nevertheless served its purpose during the attack on Sydney Harbour. Commander Newcombe’s warning of 20 January 1942 had been vindicated.

A composite example of Midgets Nos. 22 and 27 (sunk at the net) was fashioned and displayed on a 4000km truck journey around Australia (Sydney-Melbourne- Adelaide-Canberra) and it was finally installed at the War Memorial in Canberra in April 1943. Compared to the Japanese war record, the British X-craft midget submarines had achieved very important successes and had shown that it was possible to strike targets in enemy harbours and return safely to base.

Captain Newcombe is still commemorated by the instructional building named after him in the Warfare Training complex at HMAS Watson, the premier training establishment in Sydney.

Bibliography:

- Australian Official History of World War 2 – G. Hermon Gill

- Australian Anti-Submarine Officers’ Association – Ray Worledge

- The Australian (various articles)

(The author is a writer with The Australian newspaper. Ed.)