FOR more than three hours on a fine, calm August morning in 1955, the eyes of Sydney’s suburbia were fixed skyward, anxiously watching the flight of a pilotless Auster aeroplane as it circled above and headed from Bankstown to the City, pursued by Service aircraft.

It was school holiday time, the alert had gone out over the radio, and the mums had herded in their children, police patrolled areas by car, cycle and foot, firemen stood by their tenders, ambulance men remained on the alert and firefloats stood in readiness in the harbour . . . all eyes still looked up . . . no one knew when or where the plane might suddenly come hurtling down.

The end came – thankfully five miles off the coast – when two Navy Sea Furies opened fire on the Auster. which levelled out pouring smoke, then started down in a slow spiral. The two Navy pilots followed it down, firing two or three more short bursts on the way and with a splash, the errant aircraft, still in one piece, hit the water at 1142 and disappeared. It was all over!

The media had a field day . . with such newspaper headings as “Possible disaster in flight”, and “Thousands watch air drama of flyaway plane”, reaching the overseas press. Politicians asked embarassing questions and crit-icism of the Services followed as did a Department of Civil Aviation enquiry … but how, when and why did it happen?

On the morning of August 30, 1955. Mr Anthony Thrower, aged 30, of Granville, Sydney, rented an Auster from Kingsford Smith Aviation School He had completed only one circuit of his planned one hour practice when the engine failed 10 feet from the ground. Landing the plane in the middle of the strip he climbed out, swung the propellor by hand (there was no self-starter) and the engine immediately roared into life. In a million-to-one chance the brake failed to hold and although pilot Thrower grabbed a wing strut to check the plane he was quickly forced to jump clear, just avoiding the tail. Aided by a favourable south-east wind with well trimmed controls, the pilotless plane sped across the strip and became airborne. It then narrowly missed the control tower, which was subsequently evacuated, and other airport buildings then slowly circled the aerodrome at low altitude After continuing right hand circuits of Bankstown for a further 15 minutes the Auster steadily gained height and began drifting towards the city.

Bankstown Aerodrome officials alerted control personnel at Mascot who broadcast a general alarm to all aircraft as well as the police and other Government organisations. One report stated that a schoolboy might be at the controls. The police radio station at Bourke Street broadcast at almost one minute intervals the plane’s last known whereabouts.

Meanwhile, Commander J. R. W. Groves, RAN, was returning to Schofields aerodrome from exercises, with three other personnel onboard. At 0850 the Navy Auster was alerted by Mascot of the runaway plane. Nearing Bankstown they saw it at 1500ft and climbing in tight circles. Approaching to within 50 yards it was noted to be unoccupied and that the controls were fixed in the one position. The Navy lightplane continued to pursue the unmanned aircraft as it gained height passing over the Sydney suburbs of Punchbowl, Bexley, Hurstville, Rockdale, Mascot, Alexandria, Redfern and finally arriving above the centre of the city about 9.30 am.

In the meantime anxious mothers in suburbs where the plane passed over herded children, who were on school holidays, into their homes. Police patrolled areas by car, cycle and foot. Firemen stood by their trucks and ambulance officers remained on the alert, and firefloats stood in readiness in the harbour. No one knew when or where the plane might suddenly come hurtling down.

By 0953 the Auster was over Vaucluse at 5000 feet. RAAF Wirraway A20-728 departed Richmond at 1010 to join the chase. Onboard was Wing Commander D.R. Beattie and Squadron Leader Tom James. The target was contacted at 1020, 2½ miles offshore and now at an altitude of 7000 ft. Instructions were then received that they were not to open fire until the Auster was five miles offshore and there were no fishing or coastal boats below. The runaway plane continued climbing in tight orbit to 10,300ft and at 1045 hours reached a point estimated at five miles from the coast.

Two firing passes were then made with the hand held Bren gun from the rear cockpit without any noticeable effect. Before departing the Wirraway rear canopy and fairing had been removed and Squadron Leader James was so cold, it was minus five degrees celcius – that he was unable to change the magazine and his hands were sticking to the gum.

Meanwhile a RAAF Meteor had arrived from Williamtown near Newcastle and after directing it to the target the Wirraway broke off the attack and returned to Richmond. The Navy Auster, which had now been airborne some 3¼ hours, headed for its base at Schofields at about the same time.

But luck was not with the RAAF that day. Firstly a Meteor piloted by Squadron Leader Holdsworth, had been delayed some 13 minutes on departure when a Sabre preceding his departure, had burst a tyre on landing and obstructed the runway. Then after arriving in the target area, and in the Meteor’s initial firing pass from the rear, both cannons jammed after only a few rounds had been fired. Some strikes were observed on the starboard plane of the Auster.

Squadron Leader Holdsworth then requested that two more Meteors be sent and the reply was received that they were on the way in addition to two Sea Furies from the Naval Air Station at Nowra. While awaiting their arrival A77-80 made four passes directly below the runaway Auster and pulled up sharply in an attempt to dislodge it from its flight path and into a dive. However, the jet wash was not sufficient and the plane continued in the same determined fashion.

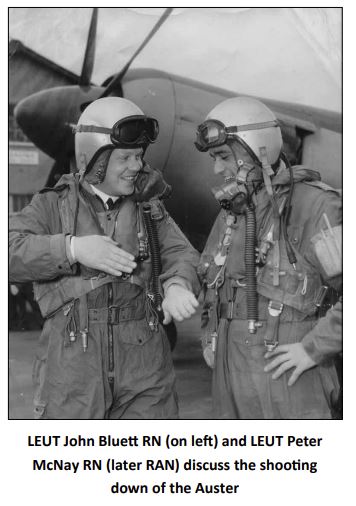

Sea Furies from 805 Squadron Nowra appeared on the scene at 1135 and were piloted by Lieutenants J.R. Bluett and Peter McNay (both aged 26), of the Royal Navy, who were on exchange duty in Australia. LEUT McNay lowered his flaps to slow down and approached to within 100 yards of the target to again confirm it was unoccupied. Then, pulling up astern he gave it a short burst from his four cannons. LEUT Bluett followed this with a beam-on attack and after about 15 rounds. a great sheet of flame rose from the cockpit. From the first strikes on the Auster until the time it hit the sea was 1½ minutes.

At 1145 a police broadcast announced “the Auster has been shot down. It’s all over.” The barrage of calls from anxious enquirers gradually subsided at the police, newspaper and radio station switchboards throughout Sydney.

When the Navy Sea Furies returned to Nowra, enthusiastic groundstaff quickly painted a small yellow silhouette representing an Auster on the fuselage of LEUT Bluett’s plane. This 26-year-old British pilot had seen eight months’ action in the Korean war from HMS GLORY on ground attack. LEUT McNay had only been in Australia eight months after completing his training in England.

The incident did not quickly subside here. Embarrassing questions were directed in Federal Parliament to. the Government of the day by both Mr C Chambers (Member for Adelaide) and Mr F Daly (Grayndler) during the Budget debate the following month. They asked why was so much money being spent on defence to an Air Force and Navy that took over two hours to shoot down an unarmed light aircraft?

Aviation authorities stated that nearly “dead calm” weather had probably prevented a major disaster as the Auster could have crashed anywhere on its route had it been a windy day. The then Department of Civil Aviation held an enquiry.

The harsh criticism against the Services was unfounded though and despite some initial bad luck the Navy and Air Force had performed creditably on a difficult and elusive “ENEMY”. In addition they were provided with an exciting Tuesday morning over and around Sydney with a free but stubborn target to practise on.

—————————————————————————————————————-