- Author

- Periodical, Semaphore

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

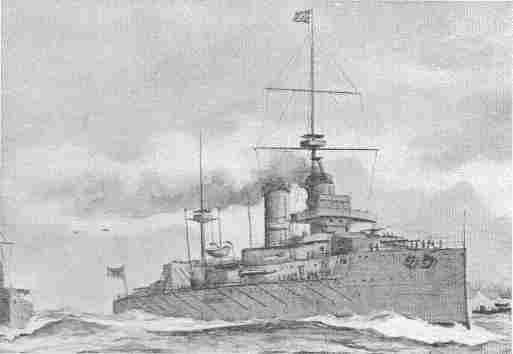

- HMAS Australia I

- Publication

- December 2009 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

This article originally appeared in the July, 2009 edition of Semaphore published by the Sea Power Centre, Australia.

A century ago, Australia’s Navy, such as it was, seemed in poor shape. The Commonwealth’s economy might have depended absolutely on ocean-going trade, but with the seas protected by the Royal Navy there had been little political interest in supporting the local navy. The Commonwealth Naval Forces (CNF) numbered only 48 officers and 147 men and possessed only an outdated light cruiser (built in 1884), nine equally elderly torpedo and gun boats, and the even older turret ship Cerberus (1870). Few, if any, of these vessels were capable of effective operations. For the CNF’s Director, Captain William Creswell, there was nevertheless some hope of progress. Years of patient lobbying had at last borne fruit and, after some additional urging, the new Australian prime minister, Andrew Fisher, had agreed to the acquisition of a destroyer flotilla that would eventually expand to 23 vessels.

To Fisher, the destroyers were to have two major functions. First, they would support any British capital ships operating in the Pacific, thereby allowing them to make the passage from home waters without being tied down by smaller, and hence less seaworthy, craft. Second, they would provide an effective means of coastal defence, thereby further encouraging local naval development. On 5 February 1909 a cable was sent to Australia’s representative in London instructing him to call for tenders for the first three vessels. Not for the last time, however, Australian defence planning was about to be impacted by events on the other side of the world.

For more than 100 years the Royal Navy had been mistress of the world ocean, but on 16 March 1909, Sir Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty, rose in the British Parliament to describe the acceleration of the German battleship construction program. The Germans, he thundered, had expanded their naval armaments industry and, unless Britain increased its own procurement of capital ships, the Royal Navy would lose numerical superiority by 1912. Alarm spread throughout the Empire. Within a week, New Zealand had offered up the funds to build a battleship. Canada and South Africa telegraphed separate offers of support. Preoccupied with its own naval plans, the Australian Federal Government was more hesitant, but New South Wales and Victoria were goaded by the press into offering the cost of a battleship between them. Amid a profusion of competing schemes, Britain invited the premiers of the self-governing dominions to a special conference where the whole question of imperial defence could be discussed afresh.

While the naval scare was an important incentive behind the 1909 Imperial Conference, it was not the only factor involved. In 1908, the Committee of Imperial Defence had begun discussions on British policy after the expected expiry of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1915. Following the signing of the Alliance in 1902 the Royal Navy had withdrawn five battleships from the China Station as an economy measure, but Japan had since earned a reputation as an expansionist nation. The Committee therefore conceded the principle that a force of armoured ships must be returned to the Pacific. The question remained how best this might be accomplished without alarming the Japanese or bankrupting the British treasury.

Jacky Fisher

Here Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher, the British Admiralty’s outspoken First Sea Lord, entered the picture. He seized on the Australian and New Zealand offers to contribute the cost of a capital ship and at the end of June 1909 urged that they should be built as battle cruisers. Fast, well armed, but lightly armoured vessels, battle cruisers were in Fisher’s mind ideally suited to oceanic trade protection missions. More ambitiously, Fisher argued that the Australian gift should form the nucleus of a credible local navy. He further hoped that the other dominions might be enticed into making similar contributions to imperial defence. The model he proposed for these fleets was what he termed the ‘Fleet Unit’; an advanced tactical formation consisting of a battle cruiser and its accompanying light cruisers; the former acting as the citadel and the latter its high-speed scouts or ‘satellites’. When combined with a local defence flotilla of destroyers and submarines, and suitable logistic support vessels, the package represented an ideal force structure for an emerging nation; small enough to be manageable in times of peace but, in war, capable of effective action in conjunction with the Royal Navy.

The adoption of such a scheme might even allow Britain to leave the Pacific’s naval defence to the dominions: ‘We manage the job in Europe. They’ll manage it against the Yankees, Japs, and Chinese, as occasion requires out there.’ Prime Minister Fisher was not a supporter of the dreadnought offer, declaring it not naval policy, but merely ‘a spectacular display’, and one that would do nothing to encourage the interest of Australia’s youth. Fisher’s hold on power was nevertheless tenuous and, assisted by the confusion over the naval issue, Alfred Deakin replaced him in June 1909.

Deakin had previously served as Prime Minister and had long been in correspondence with Admiral Fisher. His ideas for an Australian navy had thus far been based on the acquisition of a flotilla of torpedo boats and submarines, with the officers and men fully interchangeable with Imperial seamen. Yet this implied that Australians would serve in Royal Navy ships merely for the term of an ordinary commission on the Australian Station. The long-term impracticality of such an approach had done little to endear Deakin to the Admiralty.