- Author

- Periodical, Semaphore

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Australia I

- Publication

- December 2009 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Domestic considerations left Deakin unable to attend the Imperial Conference, so he sent instead Colonel Justin Foxton, Minister without Portfolio, accompanied by Creswell as his naval advisor. Arriving in London in July 1909 they brought with them Deakin’s offer of ‘an Australian ‘Dreadnought’, or such addition to (the Empire’s) naval strength as determined after consultation in London.’ They were quite unprepared for the subsequent discussion.

The Royal Navy, advised McKenna on 10 August, could no longer guarantee sea supremacy in the Pacific. In just a few years the Japanese Alliance would have terminated, both ‘the Japanese and German fleets would be very formidable’, and the position of Australia, isolated and remote from British naval strength, ‘might be one of some danger.’ Admiral Fisher added that the naval force currently planned by Australia, consisting only of small craft, could lead nowhere. A navy, he continued, had to be founded on a permanent basis and offer a life-long career if it meant to attract and retain quality personnel. In sum, Australia should aim to create and fully man a self contained fleet unit. This force provided the right proportion of officers to ratings and a coherent grouping of large, medium and small-sized ships. Joined with two smaller fleet units on the East Indies and China Stations, it would form an Imperial Pacific Fleet. Even on its own, however, the proposed Australian fleet was a formidable prospect, capable of independent action on the trade routes and sufficiently powerful to deal with most hostile squadrons.

This initiative owed little to existing Australian planning, and the Commonwealth’s delegation was uncertain of its response. Creswell had wanted a local navy to be self-reliant and had previously urged progressive development. He pointed out the advantages of Australia building what he called the foundations of naval strength – naval schools, dockyards, gun factories – rather than spending money on a capital ship. Local needs, Foxton added, dictated a larger number of smaller vessels; the protection of trade would be impossible along the entire 12,000 miles to Britain; and Australia could not afford such ships.

Control of Australia Station

McKenna reminded them both of Deakin’s earlier proposal to establish a flotilla of submarines and destroyers. The Admiralty estimated that this would have cost at least £346,000 per annum. If added to Australia’s offer of a capital ship and its annual maintenance, the total was closer to £500,000. By contrast the annual operating cost of a fleet unit would only be £600,000 to £700,000, and the Admiralty offered to fund the difference. The handing over of control of the entire Australia Station, and the transfer to the Commonwealth of all imperial dockyard and shore establishments in Sydney, made the bargain even more attractive and addressed many of Creswell’s concerns. Foxton, now convinced, agreed to communicate the proposals to Deakin and obtained the Prime Minister’s sanction to work out the scheduling details. In Australia, the Admiralty’s scheme found wide approval. Notwithstanding the lack of local input, most factions found it attractive and in harmony with their long-held ideas. Cabinet gave provisional endorsement on 27 September 1909 and work on the force proceeded rapidly with only minor changes to the selection of warships first suggested by Admiral Fisher.

Returned to power in April 1910, Prime Minister Fisher decided to refuse the British offer of financial assistance and fund the new vessels wholly from within the Commonwealth budget. A new Naval Defence Act 1910, passed on 25 November, provided the clear legislative authority necessary for the reinvigorated navy. Its key provisions included the creation of a new Board of Administration; the establishment of colleges and instructional institutions; the division of the Naval Forces into the Permanent Naval Forces and the Citizen Naval Forces; and provisions relating to service conditions, such as pay, allowances, and discipline. All such naval administration was to be based upon the Royal Navy model.

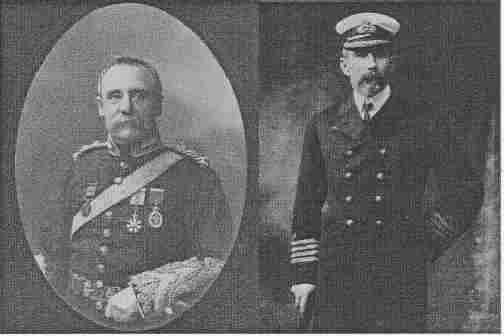

Just four years after the 1909 Imperial Conference the battle cruiser HMAS Australia steamed into Sydney Harbour at the head of Australia’s own Fleet Unit. Off Fort Denison was the British cruiser HMS Cambrian and on board was Admiral Sir George King-Hall, the last British Commander-in-Chief. As he hauled down his flag, command of the Australia Station passed to the new Royal Australian Navy (RAN). Within a year the RAN was at war and, in a succession of efficient operations, removed any threat to Australian sea communications in the Indian and Pacific Oceans; more than fulfilling the trust that had been placed in it.

By any accounting it was a remarkable achievement.