- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

A casual browse through the bookshelves of opportunity shops can produce some surprises. Disorganised, with no rhyme or reason to subject matter, it is as well to look for hard backed copies with dust jackets indicating quality and quite possibly little used, and so it was that Bimbashi McPherson came to life.

Joseph Williams McPherson (1866–1946) a classical scholar with an Oxford first arrived in Egypt in 1901. He fell in love with the country, its people and customs and stayed there until his death in 1946. During that time McPherson wrote thousands of pages of letters home, mainly to his parents and siblings. Luckily this correspondence, never intended for publication, was preserved and resulted in a series of BBC radio programmes, which were then edited by his great-nephew John McPherson to form a book named after him.

MacPherson’s letters take their place amongst that select company of writers and diarists who help illuminate the history of their times. He started in Cairo as a teacher, using his long holidays to travel and mix with local people throughout the Middle East. The First World War finds him equally at home with Australians at Gallipoli, describing the doomed campaign, and the battles of the Sinai desert. This brief story aims to place an authentic first-hand stamp on history as seen by a keen observer writing for pleasure with no need of journalistic cant pandering to a wider audience.

A new prosperous middle class seeking the best education for their sons to take their places in running the world’s largest empire gave rise to a new style of public school which sought to produce pupils of academic and physical excellence. One of these schools was Clifton College on the outskirts of Bristol; at least three members of its alumni were to meet again at Gallipoli.

Early Life

Joseph Williams McPherson was born in Somerset in 1866, the youngest of six sons in a Highland family which had migrated southwards. His parents were Covenanting Christians of exceptional fervour. His father had been an estate manager to the Duke of Gordon and after coming to England had obtained a post as supervisor of a mental hospital outside Bristol. This came with a substantial residence in the hospital’s park-like grounds.

Joseph was educated at Bristol’s Clifton College where he was well grounded in Latin, Greek, modern languages, science and literature. In 1883 he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Science at Dublin, and four years later a further scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford, where he gained a first class degree in Natural Sciences. At Dublin he embraced Catholicism. At Oxford, more mature than many of his contemporaries, he was successful athletically and socially, gaining a reputation for student pranks and high living. Through these excesses with aristocratic friends he ran up large debts which his brothers paid. After university he drifted into a career in education and ended up as a science master at his old school, Clifton College.

While he was at Oxford there is first mention of Australians, a theme which continues throughout his writings. McPherson, who remained a bachelor all his life, was involved in a love affair where he and his best friend fell for the same young lady. In the end she rejected McPherson and married the friend; after having a child she died, and the friend went to live in Australia. This may not have endeared McPherson to the antipodes.

When he was aged 35 his adored mother died which lessened home ties and, with a keen amateur interest in Egyptology, he became aware of a visiting delegation seeking a few Oxford men for service in the Egyptian administration. Presenting himself, he was offered a post with the strangely named Department of Public Instruction – subsequently the Department of Education.

McPherson arrived in Cairo 1901 and was given a post at the prestigious Khedivieh School where the sons of sheiks, brought up in a strict Muslim culture, were provided with a European style education. They were good students, well disciplined, keen to learn and also enjoying sport. While the teaching staff were mostly English and wore conventional academic robes, local custom dictated they wore the tarboosh. McPherson threw himself into this new world and mastered Arabic so completely that he could pass for a native. With his easy going personality and willingness to join and observe local customs, this meant he loved Egyptians and they loved him.

Egypt was then the most ambiguous of British possessions. Nominally, it was an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire with a head of state, the Khedive, owing allegiance to the Sultan at Istanbul. It had its own government, army and civil administration; yet for the past twenty years the British had run the country, with real power exercised by Lord Cromer, the British Consul General.

With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 Egypt became strategically important as it provided the quickest access route between Britain and its prized Indian possessions. British authority was assured by retaining a large military garrison to preserve its interests owing to the vast debts owed by the Khedive. By the turn of the 20th century the country was generally stable and provided career opportunities for bright young men like Joseph McPherson.

Journeys further afield and off to War

During holidays in 1908 McPherson travelled overland through the heart of a then restless and dangerous Turkey from its southern Syrian border to the capital at Istanbul. And again in 1913, this time by ship, he visited the centre of an Ottoman Empire in convulsive decline. In a 1911-1912 war with Italy the Turks had lost possessions in north Africa and Mediterranean islands; and in the recently concluded First Balkan War had been deprived of most of the last vestiges of their European territories. These losses led to an underestimation of Turkish resolve and it was widely considered they would be no match against British forces.

Sensing a British desire to further the disintegration of its empire, Turkey entered the Great War in November 1914 on the side of Germany. Egypt, technically a province of the Ottoman Empire, was declared a British protectorate. This highly contentious action might encourage Turkish forces in Palestine and Syria to advance across the Sinai Desert to attack the Suez Canal.

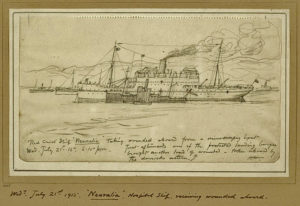

Joseph McPherson joined a volunteer reserve infantry unit formed by members of the Gezina Sporting Club, known derisively as ‘Pharaoh’s Foot’. While commanding a platoon at nearly fifty, he was out of touch with eager youngsters and this led him to transfer to service with the British Red Cross Commission. Here he joined the hospital ship Neuraliabound for the beaches of Gallipoli. Neuralia, a requisitioned British India passenger liner, carried 11 medical officers and 15 nurses in her new role and could accommodate over 600 casualties.

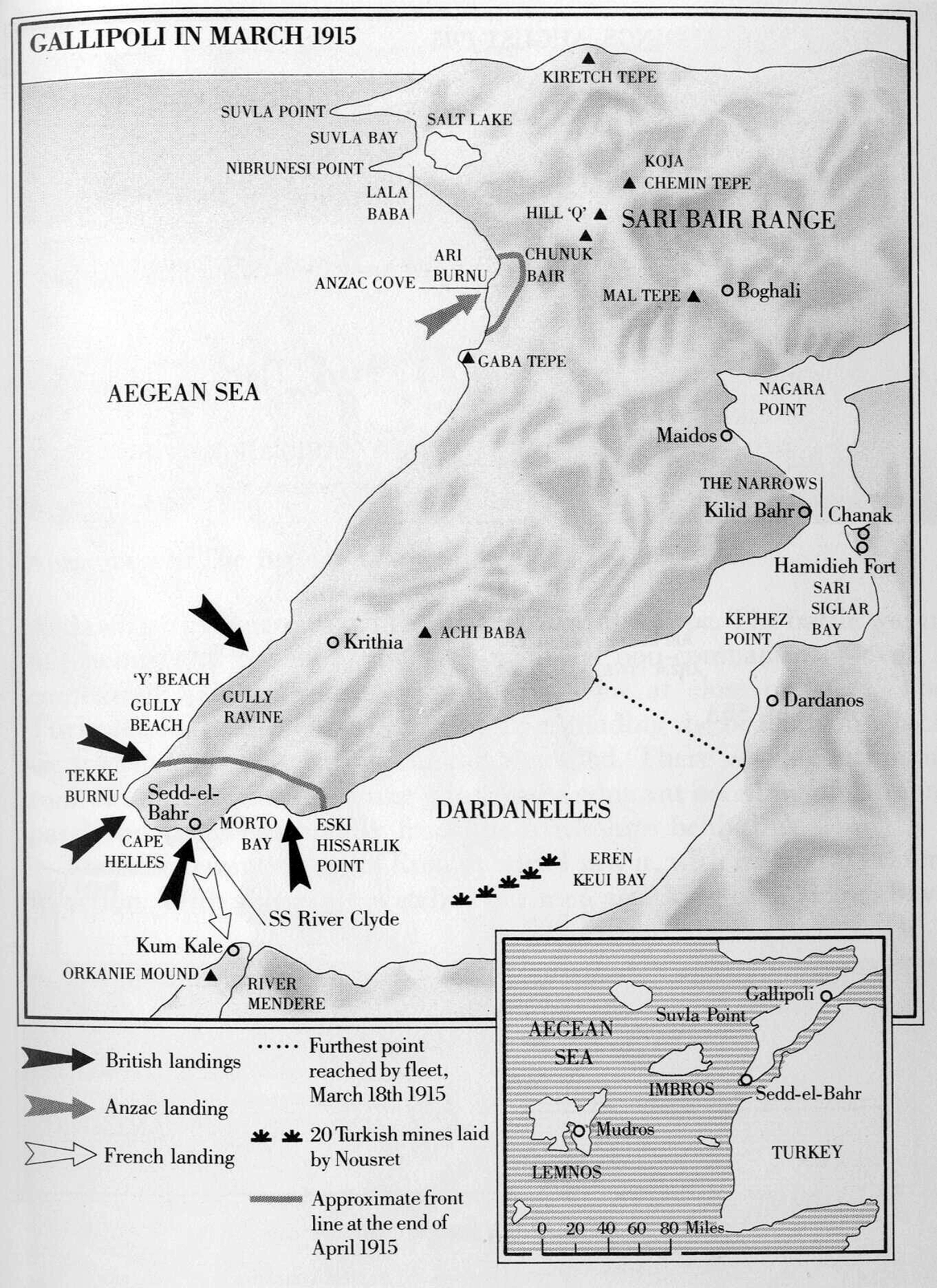

The original Allied landing on Gallipoli occurred more than three months previously with the arrival of the Anzacs on 25 April 1915. The objective was to overrun the Turkish defences and enable British and French battleships to force the Dardanelles, as a prelude to knocking Turkey out of the war. The plan failed with Allied troops pinned down on cramped beachheads.

Now a new effort was underway with massive reinforcements which aimed to break out of the Anzac beachhead and mount a diversionary assault from Cape Helles. The advancing fronts would link up and sweep the Turks off the commanding heights and then dominate the Straits. The landings north of the Anzac beachhead at Suvla Bay began on 6 August. After the first three days of battle, out of 50,000 troops the Allies suffered 19,000 casualties and the Turks remained firmly established on every vantage point.

McPherson gives a first-hand account from his ship which was ferrying casualties from the beaches to the island of Imbros. While he was involved in caring for wounded and helping with operations he was on first name terms with the medical officers and was given time to go ashore as he had letters for Doctor John (Jack) Bean who was serving as a Major in a field hospital near his brother the Australian official war correspondent Charles Bean – later to become famous for his official war histories1. John Bean had been wounded and could not be located so McPherson was taken to see brother Charles who introduced him to the officer commanding the Anzac Force, Lieutenant General William Birdwood. How does a Red Cross assistant gain entry into the inner sanctum of the war machine? The answer lies in an old school tie. McPherson and Birdwood were at Clifton together and Bean also attended the same school but was some years their junior.

While ashore McPherson suffered injury from a shrapnel burst, with septic poisoning resulting when back in his hospital ship. Having little to do because of incapacity and being able to speak Turkish he was asked to interview wounded prisoners to gauge their attitude towards their German officers. After gaining their confidence the prisoners thought their new allies harsh and tyrannical, making impossible demands. They also spoke of a dread of British naval guns and the slaughter they caused to enormous numbers of their comrades. However, they considered the war could continue indefinitely.

After this escapade McPherson was hospitalised at Mudros on the island of Lemnos. Lemnos was the temporary home for most Anzacs as it was here that they were first discharged to practise beach landings and some of them are buried on these shores. With hospital ships overwhelmed with casualties many others were buried at sea. On discharge from hospital McPherson contrived a passage in the small fleet messenger ship HMS Clifford to Cape Helles. On shore he witnessed an attack on enemy lines which ended up in another stalemate. This was to be his last glimpse of the doomed enterprise as he was soon back in Alexandria.

Keith Murdoch3 writes a Letter

When the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) sailed for Europe, a single journalist had been selected as the official war correspondent. A ballot held from nominations made by the Australian Journalists’ Association was won by Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean, and in second place was a younger man, Keith Murdoch.

Not unlike the Bean family, the Murdoch family came from a background of Scottish churchmen. Keith Murdoch was schooled at Melbourne’s Camberwell Grammar where he was dux, but he declined university in favour of journalism. In 1908, aged 22, he travelled to London, but with limited experience and an unfortunate stammer, he failed to gain employment with a major newspaper. Upon return home he was taken on by the Age as its federal parliamentary press correspondent. Murdoch was next offered a post in London as editor of the United Cable Service, supplying cable news to Australian papers.

In August 1915 on his way to take up his new position Murdoch first stopped at Cairo, waiting for permission from General Sir Ian Hamilton, to visit Gallipoli. While he waited he visited soldiers in hospital wards and began to hear rumours about the campaign from Australian officers stationed in Egypt.

‘Keith Murdoch arrived today’ Charles Bean wrote in his dairy on 3 September 1915. Murdoch had only four days with the Anzacs and there was much to see. Bean was ill during Murdoch’s visit and would shortly be evacuated. Many others were sick, with shortages of water, which was of dubious quality, and fresh food. Murdoch visited Major General Harold Bridgewood Walker (an English officer replacing the Australian Major General William Bridges – killed by a sniper in May) and called on the commander of the Anzac forces Lieutenant General Birdwood.

On his last day at Gallipoli, Bean took Murdoch to Quinn’s Post, a real hot spot where opposing trenches were only metres apart, where soldiers from both sides were ever on the alert and casualties were high. On return to Imbros Murdoch met the doyen of correspondents, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, who was well connected in British Government circles. Ashmead-Bartlett had provided the first accounts of the initial Anzac landings published in Australian papers. He had written of ‘this race of athletes’ and that there had ‘never been a finer feat in this war’ than the April assault. By now Ashmead-Bartlett was disillusioned, firmly convinced that the army must be evacuated if a mighty loss of life was to be avoided. As a first step he believed Ian Hamilton had to go for the failure of the campaign, and because he would never agree to an evacuation.

Discussions with Ashmead-Bartlett only served to convince Murdoch of the hopelessness of the campaign. His journey from Imbros to Egypt and thence London provided plenty of time for Murdoch to hone a letter to Australian Prime Minister Fisher. This became known as the letter that changed the course of the Gallipoli campaign. It is a passionate piece of journalism protesting against the conduct of the campaign and vividly describing conditions at the front. Murdoch firmly blames the commander of the Expedition and his staff, saying:

…But this unfortunate expedition had never been given a chance. It required large bodies of seasoned troops. It required a great leader. It required self-sacrifice on the part of the staff as well as that sacrifice so wonderfully and liberally made on the part of the soldiers. It has none of these things. Its troops have been second class, because untried before their awful battles and privations of the peninsula. And behind it all is a gross selfishness and complacency on the part of the staff.

Whether coincidental or not, following receipt of this letter, Lieutenant General Sir Ian Hamilton was recalled and, in one of the few pieces of masterful organisational ability of the campaign, the troops withdrawn with minimal losses. The total number of Allied troops involved at Gallipoli was 490,000 including British, Indian, Canadian, French and 50,000 Australian and 15,000 New Zealanders. They fought against 316,000 Turks supported by 700 Germans. About half those on either side became casualties, including 26,111 Australian of which 8,141 died and 7,991 New Zealand casualties with 2,779 deaths. Of those who survived some were sent to the Western Front, some to Mesopotamia, and others fought their way across the desert from the Suez Canal to Jerusalem and Damascus.

The Camel Transport Corps and the Egyptian Labour Corps

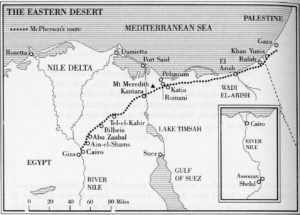

After four months with his arm in a sling McPherson was pronounced fit and sought a commission as a captain in the newly formed Camel Transport Corps (CTC). New battle plans called for an offensive campaign to confront and drive the Turks from Palestine. The task of the CTC was to supply the fighting troops with stores, particularly water, and carry back the wounded. A camel carried two fantassas or water tanks each of 15 gallons.

Recruitment proved difficult resulting in drives through poorer regions where impoverished labour could be bought and at times press gangs were sent in. During its four-year history the Camel Transport Corps acquired 72,500 camels and 170,000 natives passed through as drivers. Also of immense importance was a newly formed Egyptian Labour Corps to assist the fighting troops, and by the end of the war 1.5 million Egyptians had served in it. After the war men serving in this force were one of the prime causes of nationalist upheaval.

There is an interesting comment by McPherson on life in a training camp for both men and beasts. To retrain camels is always difficult and I have yet to meet the hero who will stand up to the really mad man-eating camel. The Australian officers undertook to lasso them, but I never knew them to succeed, except on one occasion, when the lasso went well over the animal’s neck, the camel bolting with about a dozen natives hanging on to the rope and the Australian as well. They then charged through and pulled down some temporary buildings.

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) that advanced from Suez into Sinai was a colourful mix from British county regiments, Australian Light Horse, New Zealand Mounted Rifles, Indian Lancers, Imperial Camel Corps and the Hong Kong & Singapore Camel Battery. Against them were Turkish forces well used to the desert, aided by German aircraft. To defeat the Turks, the British had also to subjugate the desert, and a vital part of the plan was the laying of a railway and water pipeline to parallel their advance.

The Battles for Sinai and Gaza were hard won and it was during this time that McPherson was to gain the services of Gad El-Moula, an assistant who was to remain with him for the remainder of his life. With supplies brought first by the CTC and then as the railway and pipeline progressed the EEF greatly outnumbered the enemy. By late January 1917 after the Battle of Rafa where 2,000 Turks were surrounded by the Australian Light Horse, New Zealand Mounted Rifles and other mounted yeomanry and cameleers, they were obliged to surrender, and the Sinai had been won.

McPherson witnessed the introduction of new forms of warfare and was full of praise for the reconnaissance value of aircraft but not impressed at their bombing capabilities. The troops were in raptures when watching dog fights between opposing aircraft. He was dismissive of the value of a squadron of eight tanks sent into battle at Gaza with two becoming bogged in the sand and a third destroyed by Turkish shell fire. Interestingly in 1917 when these new forms of warfare were being tested the major motive force remained with camels and horses.

The First and Second Battles of Gaza in southern Palestine where the EEF fighting force of 31,000 was pitted against 19,000 in well defended positions was a far more severe test of Allied resolve resulting in numerous casualties of men and camels. These battles could only be classed as defeats and the Imperial Government, desperately worried that this could become another Gallipoli, took early action to replace the lacklustre commander General Sir Archibald Murray. He was replaced by a larger than life cavalry officer General (the Bull) Sir Edmund Allenby3. Given reinforcements, the reinvigorated EEF broke the Turkish lines and the road lay ahead beckoning them towards Jerusalem.

Farewell to Arms

At the end of April 1917 McPherson was wounded in the leg by a sniper’s bullet. This was his second wound of the war, and as he had already been savaged by a camel and taken heavy falls from his horse he was pulled out of the front line and ordered back to base in Cairo. In May he was promoted major (Bimbashi) and appointed to take charge of political prisoners, mainly Egyptian nationalists. This must have given him a new lease of life as a few months later McPherson was promoted to the important position of Chief of Secret Police (Mamur Zapt), and plunged into a world of crime and political intrigue.

In 1919 the victorious leader of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, now Field Marshal Lord Allenby, was appointed High Commissioner for Egypt and Sudan, a position he held until retirement in 1925. McPherson was distrustful of Allenby’s appeasement to militant nationalists which he believed led to further unrest. McPherson’s subtle disapproval was noted in his failure to attend Vice-Regal receptions.

The position of Mamur Zapt provided immense power to search, arrest and detain on the least suspicion. McPherson was at pains to maintain scrupulously high standards of integrity and to outlaw corruption in his new domain. In the spring and summer of 1919 riots and demonstrations occurred in the cities and provinces, trains were derailed, stations burned and troops and civilians attacked and killed. At least 1,000 Egyptians died in clashes with British troops attempting to suppress insurrection, and in turn, about 100 Britons were killed or injured. During this time members of the Secret Police came to the aid of a patrol of Australian Light Horse attempting to break up a demonstration. Dykes, the secret policeman in charge, was shot twice in the back and died as a result. Dykes was McPherson’s assistant and the event greatly disturbed the Mamur Zapt.

Even here the Australian connection continues with the Secret Police sent to investigate the dealings of a beautiful she-devil and queen of crime suspected of involvement in suspicious deaths of some servicemen. When it transpired her lover and protector was a sergeant in the AIF, their business was closed and both were packed off to other pastures.

In August 1920 the now Colonel Joseph McPherson sailed for three months’ home leave. Shortly after return he was found a new position in Intelligence and Passport Control becoming involved with immigration and an ever-increasing conflict between Arabs and Jews. Unrest against British authority continued, culminating on 19 November 1924 in the assassination of General Sir Lee Stack the Sidar (Commanding General) of the Egyptian Army and Governor of Sudan. It was into this continuous unrest that the son of a post office official grew up and developed influence as a leading figure fighting for independence, later gaining worldwide prominence as President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Retirement

Early in 1925 Bimbashi McPherson retired from the Egyptian Public Service and bought a small holding with a picturesque dwelling not far from Giza. Here with the faithful Gad and Gad’s increasing family he established an idyllic little farm growing maize and cauliflowers and keeping sufficient stock for their needs, including a cow, donkeys, goats, rabbits, ducks, geese, doves and chickens, plus pet hounds.

The Bimbashi remained in Egypt throughout WWII and afterwards on 18 January 1946 travelled to Cairo. Here he contracted a slight chill but returned home. Four days later, when upon waking his servant handed him a hot drink to sip, he suddenly fell back and breathed his last, well content in his 80th year. He is buried in Cairo with a tombstone bearing the single word inscription XAIPE, from the ancient Greek meaning Rejoice.

Notes:

- 1. Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (1879-1968) gained a second-class honours degree from Oxford which precluded his first choice of entry into the Indian Civil Service, if this had eventuated we might never have had the advantages of his service to this country.

- Arthur Keith Murdoch (1885-1952), later Sir Keith, was a journalist and newspaper proprietor who gained control over a number of newspapers and radio stations throughout Australia giving his organisation immense influence. He was the father of Rupert Murdoch who through News Corporation continues to maintain political influence in Australia, Britain and the United States.

- Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby (1861-1936) was educated at Haileybury and failed the Indian Civil Service examination. This was the army’s gain as ‘The Bull’ – known for his physique and roar – knew how to win. On arrival in Egypt he received the devastating news that his only child had been killed in action. Despite grief he threw himself into work with great determination which his officers and men respected and thus he revitalised his forces.

References:

Bean, C. E. W., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Vols 1 & 11, The Story of ANZAC, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1934.

Carman, Barry & McPherson, John (Edit), Bimbashi McPherson – A Life in Egypt, British Broadcasting Corporation, London, 1983.

FitzSimons, Peter, Gallipoli, William Heinemann, Sydney, 2014.

Gullett, H. S., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Vol VII, Sinai & Palestine, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1923.

Murdoch, Keith, The Gallipoli Letter, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2010