- Author

- Book reviewer

- Subjects

- Book reviews, History - post WWII

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

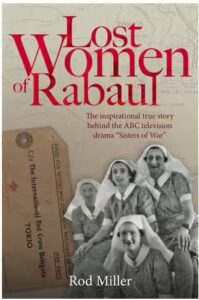

Lost Women of Rabaul by Rod Miller, 2022, Big Sky Publishing, Newport, NSW, PB 350pp, RRP $32.99

Lost Women of Rabaul by Rod Miller, 2022, Big Sky Publishing, Newport, NSW, PB 350pp, RRP $32.99

This review first appeared in Reconnaissance, the magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales, No. 52 Summer 2022, and is kindly reproduced by permission of the Author and the Editor of the magazine.

Lost Women of Rabaul is author Rod Miller’s first publication, and comes after eleven years of research, plus the associated tragic story of the Montevideo Maru in 1942 (sunk that year carrying Australian POWs from Rabaul to Japan, though none of the women in his book were on board).

Miller chronicles the story of eighteen Australian women (nurses and civilians) captured at Rabaul in January 1942, after the Japanese invasion of New Britain following their stunning and swift advance through south-east Asia after the attacks on Pearl Harbor that month. Rabaul was not only a strategic deep seaport, but since 1922 had been the administrative capital of the Australian Territory of New Guinea. Therefore, it was Australian territory, albeit far removed from the Australian mainland.

The ‘lost’ women were a mixed group, comprising seven civilian nurses from the government hospital, four Methodist mission nurses, six Australian Army nurses and a lone civilian plantation owner. Their story is unique in that they were the only females captured within Australian territory during the war and then transported to Japan.

The story of the disastrous defence of Rabaul by Australian forces, whilst not central to this story, is relevant since the women were based at Rabaul or had been evacuated there for safety. The capture of these women on ‘home soil’, and their transportation to Japan where they languished for three years and nine months, seemingly unknown to the Australian authorities and the International Red Cross, forms the basis of the book.

Miller, an auctioneer, in 1991 purchased the diary of one of the women (civilian nurse Grace Kruger) while clearing a deceased estate. The diary was odd, written in a school exercise book which used cryptic prose, nicknames, Pidgin English, shorthand and ‘language of the day’ (now viewed as racist). Grace may have used these methods to conceal the true meanings from her captors. The original book’s pages had been added to with other paper, sewn into the centre of the book (while in Japan, one of their tasks was to make envelopes, and the extra paper probably came from this source).

Miller was initially stumped, but was eventually successful following some hard work, luck and good fortune. During his research he spoke with some of the surviving captives (in the late 1990s and early 2000s, before their deaths), as well as chancing across a diary written by another of the captives. This diary copied that of Kruger’s but also explained some of the terms and words used.

Subsequent contact with the surviving women and family members, plus further research, allowed Miller to locate another six of the women’s diaries − these plus memorabilia and photographs finally provided him with a nearly complete picture of their time in Japanese hands.

Miller’s research provided the impetus for the ABC 90 Minute drama, Sisters of War, produced in 2010, that received wide acclaim.

In July 1942, the women were all transported to Japan, together with Australian military officers, also captured during the fall of Rabaul. Landing in Yokohama, their treatment seemed more like that of ‘tourists than internees’, since they had to clear customs upon arrival! Their lodgings were first at a hotel, then at the former Yokohama Amateur Rowing Club. As the bombing of Yokohama and Tokyo increased, they were transferred to the countryside.

The situation with this group of Australians was in stark contrast to how others often fared when captured by the Japanese, such as the infamous Bangka Island massacre of Australian nurses who had been captured fleeing Singapore. But for this group, their time in captivity over the next three years was different, although threats of violence and assault were always present from their military and police guards. Infractions such as questioning orders or failing to bow correctly and the like were met with slaps and other physical abuse, but overall the group escaped the harsher physical punishments (and capital punishment) that many others endured while in Japanese hands.

However, as the months and years progressed, their conditions deteriorated, especially their physical and mental health, together with the rations, clothing and medical situation. Changes of guards and their accommodation, the worsening scarcity of food supplies, the increased bombing of Japanese cities, the rumoured Allied victories and advance on Japan (countered by the news gleaned which focused on Japanese victories) plus the vanished likelihood of being exchanged all eventually took their toll. They were put to work, but while this allowed them to earn a very meagre amount of money (pooled to secure supplies), life for the group seemed to drag on day in, day out.

Their pitiful conditions strike home evoking some powerful images. As noted, one task was making envelopes, and later they reverted to eating the glue from these to supplement their diet. Grace notes they were ‘… eating weeds and boiling rusty nails and drinking the water in an effort to stave off the pangs of hunger.’ Throughout their ordeal, the women did receive some relief packages, mainly through the American or Japanese Red Cross services. These deliveries were few and far between, and often occurred before a scheduled visit by a high-ranking Japanese official.

As the story progresses the tone reflects the increasingly dire situation faced by the women, and this is where its strength lies; concentrating on the individuals, their feelings and their attitudes towards their situation and the military and civilian Japanese they encountered. The promise that the reader will ‘witness the intrigues of international diplomacy’ and ‘confidences betrayed’ and ‘what were the international secrets that determined their fate?’ are lofty statements and questions that were not fully explained in any great detail. But in Miller’s defence, there is a lack of detailed documentation on the women and their time as captives across the usual archival sources. This is simply because they ‘disappeared’ into Japan, where they were either neglected by Australian authorities or their actual prisoner status seemed to be too difficult for the Japanese to accept. A post-war enquiry into the fall of Rabaul, the surrender of the Australian forces and the fate of those captured failed to properly account for the lack of information known or sought by Australian authorities about those captured in 1942.

Once in Yokohoma, through contact with high-ranking Japanese officials who visited them, the group was led to believe that they would be eligible to be sent back to Australia via a neutral nation. Their status as non-combatants raised their hopes that an exchange between Japan and the British Government (who represented Australia at the time) was possible. However, only two such exchanges took place, and this group was never put forward, raising the question as to why. Miller concludes that ‘we will probably never know why the women were not exchanged’, although he speculates that embarrassment by the government in failing to secure their exchange saw Australian files being ‘heavily culled’ before being archived.

This hint of a plot of sorts, or wilful neglect by Australian officials, clouds Miller’s reasoning when he states: ‘It is also possible, but unlikely, that the women were simply casualties of an overly bureaucratic exchange system, which had promised much but delivered very little.’ More likely the group was part of a cataclysmic conflict, which engulfed huge tracts of the Asia Pacific, often at lightning pace with the initial Japanese advances, followed by their dogged defence and then hard-fought victories by the Allied forces as they clawed back invaded territories from 1942 onwards. A relatively small group of women, once transported to Japan, were at the mercy of their captors. Much has been written about those who became prisoners of the Japanese and their mindset towards their prisoners, yet the true extent of many incidents only became clearer following the Japanese surrender.

The result of Miller’s research is mixed. The book’s strength is where the courage, resilience and determination of the women is evident, even as their imprisonment entered its fourth year. The post-war accounts of the women does provide an element of closure on their lives following liberation, but even here the story could have been expanded to ‘complete’ their lives. While the focus was their wartime capture and imprisonment, we remain curious about how ordinary people cope, react and survive following their experiences which others find hard to relate to. How individuals ‘survive’ the peace is just as compelling as how they survived a war. In this case, the Army nurses received government benefits and ongoing medical treatment, while the civilians were omitted from this process.

Lost Women of Rabaul certainly does add to the historical record and Miller should be congratulated for pursuing this over the years. While the nature of the book relies heavily on the diary entries, it certainly highlights a story that is worthy of attention, focusing on an episode that few would be aware of, reflecting that even some 80 plus years after the war commenced there are still fascinating stories to tell. This book complements other elements of his research and it would be worthwhile seeking these out (by viewing the ABC movie and visiting his website) to gain a better understanding of this resilient and resourceful group of women in their years of captivity.

Reviewed by John Hall