- Author

- Book reviewer

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Book reviews, Biographies

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

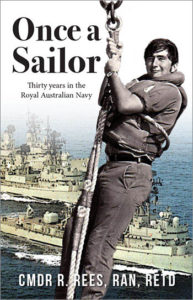

Once a Sailor. Soft cover of 324 pages by Ray Rees. RRP $32.95 also available from author Ramon.Rees@yahoo.com.au. Published by Vivid Publishing, Fremantle WA 2021.

The author joined the RAN as an apprentice, went on to graduate from RMIT with a Bachelor’s Degree of Engineering before progressing through the commissioned ranks and later, after completing the RAN Staff Course, gained an MBA. This book covers a naval career from joining HMAS Nirimba in 1975 until he transferred to the Royal Australian Naval Reserve list in 2005, a career lasting 30 years and continued to this day as a contractor to the Department of Defence.

The author joined the RAN as an apprentice, went on to graduate from RMIT with a Bachelor’s Degree of Engineering before progressing through the commissioned ranks and later, after completing the RAN Staff Course, gained an MBA. This book covers a naval career from joining HMAS Nirimba in 1975 until he transferred to the Royal Australian Naval Reserve list in 2005, a career lasting 30 years and continued to this day as a contractor to the Department of Defence.

Starting as an apprentice shipwright he rose through the ranks to Engineering Commander and served in the carrier HMAS Melbourne, the destroyer escort HMAS Derwent, the tanker HMAS Success and all three DDGs. Additionally, he served in ship upkeep support services in Australia and the United States.

Ray sticks to his naval career and only briefly mentions family when it is needed to understand naval service includes all those involved with the career process. Also, he does not name individuals in his story. This does not distract from the text, which flows well from posting to posting.

The reader is taken through a journey from a very junior rank to senior management and covers his more interesting roles such as Marine Engineering Officer of the DDG HMAS Brisbane and Repair Officer at the USN San Diego Naval Repair Station in great detail. Ray discusses the good and the bad of his career and gives thoughtful analysis of the direction that the Navy has come over the 30 odd years since he joined.

For much of his time the fleet was engaged in Southeast Asia with occasional deployments into the Indian Ocean but in 1990 a progressive switch to supporting the war against terror in the Middle East saw the Navy’s focus shift towards this region. Ray was in Success during the opening phases of the war to free Kuwait and hence experienced some of this change. He also experienced the changing focus brought by the transition from a carrier-based fleet to one where the emphasis moved towards the FFG, supported by the ANZAC destroyer force.

In the engineering world the advent of the FFG and ANZAC class meant that the once predominate steam propulsion was phased out and gas turbines and diesel engines became the heart of naval propulsion. This became the catalyst for a change in the way the fleet was supported and indeed, the depth of training for sailors. Like many changes the impact was not smooth, being underestimated in some areas and overestimated in others.

In 1992 the Navy introduced the Technical Training Plan which saw the closing of Nirimba and the introduction of modular training utilising the civilian TAFE system to deliver much of this training. This saw a move from trade training to technician training. Additionally, the navy outsourced more maintenance to industry which further reduced the repair skills in the navy, particularly in traditional skills such as electrical and structural repair.

Within this context Ray discusses some of the issues he encountered in ship maintenance. Some issues were common to both the USN and the RAN, such as the price penalty paid for allowing subcontracting to low levels where in one case he cites the actual repairer was asking for $13,000 for a task but after several management fees and profit margins were added he was looking at a $200,000 bill.

A particular issue Ray had on his return to Australia was that support of naval ships moved to a centralised bureaucracy where too little control of the resources was exercised by those directly supporting the ships at the waterfront. The SPO concept had been established to allow the repair organisation to manage ships by class, with sufficient money and resources to get the ‘biggest bang for the buck’ in terms of ship availability. However, stores purchasing was centralised to get the best price but communication between the planners and the buyers often led to the wrong items being purchased.

Resources for support were often predicated on the criticality of the ship class so a modern destroyer class consisting of eight identical designs had significantly more resources than an organisation supporting 18 older ships of differing types. While this may seem to make sense to the layman, to sustainment professionals the older ships of different designs absorb much more engineering labour.

His story is one any technical sailor of the period will recognise but his descriptions of ships and equipment does not require a technical mind. This book is thoroughly recommended to anyone with an interest in the sea and in people growing through life’s journey.

Reviewed by Liz Colthorpe