- Author

- Book reviewer

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW2, Book reviews, Biographies

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Perth I

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

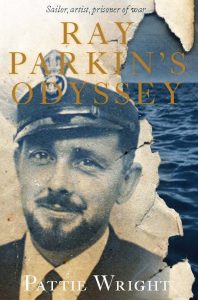

Ray Parkin’s Odyssey by Pattie Wright. Published by Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney, 2012. Hardback of 672 pages with over 100 excellent paintings and sketches, rrp $49.99.

The story of the short but gallant life of HMAS Perth was known to me from teenage years. A Naval College colleague had lost his father with the ship and a relative was a survivor. A sail at Flinders Naval Depot commemorated the boat voyage of some survivors. I was serving in Perth II in 1968 when David Burchell, accompanied by some 25 Perth I survivors, presented the ship with some artefacts he had recovered from the wreck. By then I was aware of one survivor in particular, Ray Parkin.

During the 1960s he published a trilogy based on the sinking of Perth and the experiences of the survivors. In 1997 he published the definitive account of HM Bark Endeavour. When Perth III was to be launched in 2004, Ray Parkin was planning to attend. Sadly his health precluded this and so I never did meet a man I admired and knew through his writing. Someone who did meet him was Pattie Wright, a writer and film producer. In researching the life of Sir Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop for a movie she made contact with many who had known him. One of her contacts was Ray Parkin whose survival of the sinking ended with captivity in Java, Singapore, Thailand and Japan. There was much about him that led her to write his biography.

She saw in him a man with the limited formal education of the day who emerged as a natural leader in the desperate circumstances of captivity by the Japanese. Whilst many around him despaired and became introspective with the harshness and uncertainties of their situation, Parkin realised the importance of looking for the positives despite the climate, brutal guards, wretched food and continual struggle to maintain reasonable health. He saw the beauty of the butterflies and flowers of the jungle and urged his shipmates out of their despair.

From boyhood Parkin developed a talent for sketching and painting. When he joined the Navy in 1928 he took his paint box with him. In 1939 he was a petty officer and part of the commissioning company of Perth I. With paintings and diaries he recorded the harrowing experiences of Perth and her company during the Mediterranean campaign. Perth returned to Sydney in August 1941 for a refit and a new commanding officer, Captain ‘Hec’ Waller. A third of her company were posted out and replaced with fresh men. Petty Officer Parkin remained with the ship when she sailed north in February 1942 to join the disparate force of allied ships under the command of Vice Admiral Helfrich, RNN. Perth and USS Houston survived the confused action of the Battle of the Java Sea, only to be trapped in the Sunda Strait. With others, Parkin struggled ashore to an island. They happened upon a merchantman’s lifeboat and planned to make their way back to Australia.

The perils of the sea forced them to surrender to the Japanese in Tjilatjap in southern Java. Parkin was determined the story of Perth would be told and risking harsh retribution from his captors, he kept diaries for the next three and a half years. He also painted scenes in the prisoners’ camps. His subjects ranged from the beauty of colourful butterflies and flowers to the ghastly reality of two men with malaria assisting a near death cholera victim.

Pattie Wright met Ray Parkin when he was 90 and found a man she described as one of the most unexpected, challenging and life-changing people to have crossed her path. After several meetings she arranged a film crew to record further interviews. He introduced her to his paintings, diaries, letters and published and unpublished writings. Over the next ten years she made contact with Parkin’s fellow POWs and their families. Her bibliography lists 111 authors and numerous letters, newspaper reports and private papers. Most of all she has found in Parkin’s diaries a determined survivor. From these records she highlights the rigours of the Burma railway, the antipathy between soldiers of the 7th Division and the 8th Division and their disdain for the Dutch. She is able to highlight the difficulties following the repatriation of the prisoners of war – how they felt unable to discuss their experiences and the physical and mental problems that haunted many for years, even forever. There is no doubt she admires her subject, however she is not averse to mentioning his foibles and unfashionable attitudes. The book uses 40 of Parkin’s remarkable paintings of the world around him, many painted and hidden from his brutal captors in Java, Thailand and Japan.

Pattie Wright has presented the 95 years of the life and times of Ray Parkin in a most readable style and his admirers are certain to seek out this book, particularly those with a maritime background. Seafarers will find that Pattie Wright is not familiar with the maritime idiom and her book would have benefitted with the services of a saltwater proof reader.

Reviewed by John Ellis