- Author

- A.N. Other and NHSA Webmaster

- Subjects

- Naval technology, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2005 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The Carley life-float (Admiralty Seamanship Manual 1956 terminology) was the principal method of lifesaving equipment during WW2, fitted to all warships, and not superseded by the present form of inflatable life rafts until the mid 1950s.

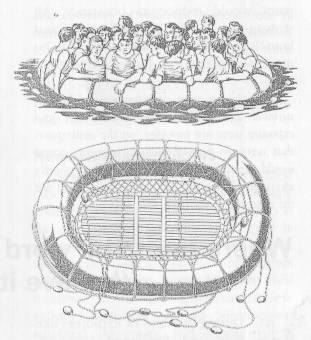

It was designed to float either side uppermost and comprised a copper tube of large diameter formed into an oval ring and divided by internal bulkheads into watertight compartments. (A shrapnel-damaged example, reputedly from HMAS Sydney – sunk in action with the German raider Kormoran in 1941 – is on display at the Australian War Memorial, Canberra). Each compartment was fitted with an air-valve to enable it to be air-tested for watertightness. The body of the raft was covered with a layer of cork parcelled with grey-painted canvas. A platform of slatted wood was slung from the inner edge of the oval body of the float by rope netting and a life-line, fitted with wooden or cork floats, was becketed round the outer side of the raft.

The float (raft) was fitted also with a painter (line), a buoyant light, a wooden box containing water in tins and emergency equipment, and a set of wooden paddles which were to be secured to the raft by lanyards at intervals, rove through holes drilled through their grips.

The rafts were supplied to the RN and HMA ships in two sizes and each size was designated by either its Pattern number or (more usually) by the number of persons (survivors) it was rated to support, both inside and outside the raft (eg a 20-man raft would support 12 men inside on the platform and 8 more outside clinging to the beckets of the lifeline). The rafts could be stowed in a nested stowage flat on deck, on platforms such as the tops of turrets, on sloping skids, or upright against a screen near the ship’s side. They could also be slung upright from the sides of the superstructure or from the shrouds of a mast, whence they could be slipped to fall clear of the ship’s side into the water. When slung from the superstructure, the sling comprised three legs spliced on a ring; the two lower legs shackled to eyebolts in the superstructure and the upper leg held by a rigging slip shackled to an eyebolt in the superstructure.

The rafts were not to be repainted because the weight of successive coats of paint would reduce its buoyancy. All stowages, slings, equipment and launching arrangements were to be inspected at least at 6 monthly intervals.

(The longer term considerations of human survival and protection from cold, wet and exposure were not provided, on the assumption that survivors from shipwreck or enemy action would normally expect to be picked up shortly afterwards. This was all too frequently just not the case, out in the open sea. Ed)