- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2012 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

These small isles to our north represent a microcosm of historical events taking place on a larger world stage. They encompass early exploration, colonial rule, resource booms, communications technology, and the impacts of two world wars and, in more recent times, have become a staging post in the migration of refugees from our Asian neighbours seeking the safety of Terra Australis.

Where are they?

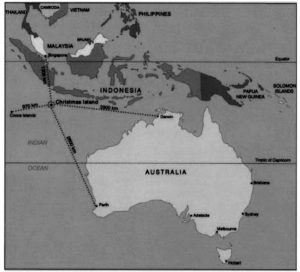

Confusion can arise over the Cocos and Christmas Islands as there are two sets of islands with the same name, one in the Indian and the other in the Pacific Ocean. Ask a New Zealander to take you to Christmas Island and you are likely to end up just north of the Equator at the Pacific’s largest atoll. This Christmas Island was first discovered by Captain James Cook in HMS Resolution on Christmas Eve 1777. It is now part of the Republic of Kiribati in what used to be known as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands.

However, an Australian colleague would have you believe Christmas Island lies in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Java. Similarly with the Cocos Islands, one with this name is found off the coast of Costa Rica and forms a part of that country’s jurisdiction while another with the same name lies again off the coast of Java.

To add to the confusion the early Malays knew a group of low atolls covered with coconut palms as the Kelapa Islands, which is the local word for coconut. The botanical name for the coconut palm is Cocos nucifera, hence in English they were referred to as the Cocos Islands. When first officially discovered by Europeans and marked upon East Indian Company charts they were named after their discoverer as the Keeling Islands.

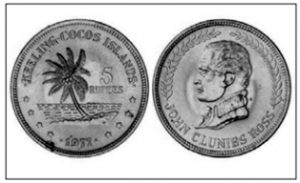

During later years they were known as the Cocos or Keeling Islands and then in the 1950s they became the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

Australian Indian Ocean Territories

At Australia’s request, sovereignty of Christmas Island was passed to Australia in 1958. To compensate the Singapore Treasury for lost customs and taxation revenue the Australian Government made an ex gratia payment of £2.9M to the Government of Singapore. Sovereignty of the Cocos Islands was also transferred to the Commonwealth of Australia with Mr Harold James Hull appointed Administrator on 23 November 1955; LCDR James Hull, VRD, RANVR had previously served in the PNF. In 1978 the Clunies-Ross family sold most of their interests to the Common-wealth for $A6.25M.

Since 1997 Christmas and Cocos Islands together are known as the Australian Indian Ocean Territories and share a single administrator based at Christmas Island. Their history is interesting to the RAN and while much is known from WW I, the sensational incidents from WW II are largely forgotten and go mainly unrecorded in Australia’s official historical record.

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands

I am glad we have visited these islands; such formations surely rank high amongst the wonderful objects of this world. Charles Darwin 1836

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands consist of two low-lying coral atolls with a total land mass of just over 14 km2. The smaller atoll, North Keeling Island, comprises just one C‑shaped island of 1.1 km2 with a small central lagoon. About 24 km to the south lie the South Keeling Islands, which is a larger atoll consisting of 24 islets forming an incomplete ring enclosing a large lagoon about 15 km long and 10 km wide which is navigable by small vessels and provides a safe anchorage. They were first sighted in 1609 by an East Indiaman Red Dragon under the command of Captain William Keeling, at which time they were uninhabited. In 1825 a British shipmaster and merchant John Clunies Ross landed to investigate the feasibility of a settlement on the Cocos Islands and the following year another merchant and Ross’s employer, Alexander Hare, arrived with a number of retainers and made the first permanent settlement. When Clunies Ross returned with his party five months later, disputes broke out and most of Hare’s people deserted and sided with Ross. Clunies Ross, his family and new retainers were left in sole possession of the Island in March 1831.

HMS Beagle with Charles Darwin embarked arrived in April 1836 when it was noted Captain Ross and his family together with 60 to 70 followers of mixed race were living on the islands. In 1857 the islands were annexed to Britain and subsequently placed under the administration of Ceylon and later the Straits Settlements. In 1886 Queen Victoria granted the islands in perpetuity to the Clunies Ross family. The head of this industriously self-sufficient Anglo-Malay clan was sometimes termed ‘King of the Cocos’.

The Clunies-Ross family

The Clunies and Ross clans which come from the remote Shetland Islands off the rugged north east coast of Scotland can trace their lineage back many generations with Ross being an established county family. John Clunes, (sic) a local schoolmaster, married Elizabeth Ross, a younger daughter of the predominant Ross family. A year later on 23 August 1786 their first child John Clunies Ross was born. The youngster assumed his mother’s name and was first known as John Ross; in later times, possibly to avoid confusion with another merchant with a similar name, he became known as John Clunies Ross. A hyphenated version of the name was adopted by later generations.

At the age of 13 John Ross went to sea as an apprentice in a whaling ship and by his early 20s he had risen to become a junior officer and held the important position of harpooner, indicating he was an excellent seaman of great strength. Returning from a whaling voyage to the Southern Ocean in May 1813 his ship called at Timor for fresh provisions. Here lay the armed brig Olivia in need of a commander; in accepting this position Ross had to forfeit his considerable bonus payment due at the conclusion of the whaling venture. Ross now became an employee of the successful Eastern merchant house of Hare and Company and was master of at least two of their ships before being appointed manager of Alexander Hare’s estate at Banjermassin in southern Borneo. The local Sultan had granted Hare a 14,000 square mile estate (more than half the size of Tasmania) with over 500 retainers. In 1812 Stamford Raffles, when Lieutenant-Governor of Java, appointed Alexander Hare as British Resident at Banjermassin. A pen picture of Captain John Ross from a Dutch official of this time is of …an open hearted round seaman, a frank, plain spoken sailor. While this should have been the start of a successful career, the political intrigues between Britain and Holland worked against Hare; in 1819 his estate was confiscated by the Dutch and Hare and Ross were forced to leave Borneo.

Using his own vessel Borneo, Hare and some of his retainers took up residence on a farm near Cape Town while Ross continued as master of the ship on a trading voyage to England. Here in 1821 he married Elizabeth Dymoke, a native of Hampshire, and a year later their first child John George Clunies Ross was born. Ross continued on trading voyages and on one of these in December 1825 he called at the Cocos Islands and cleared some land for cultivation with the intention of returning and establishing a trading settlement. With his contract with Hare & Company nearing its end Ross took his wife, mother-in-law, five children, and a maidservant in Borneo, arriving at the Cocos on 16 February 1827. Here he was surprised to find Hare, who had established a seraglio or harem with a number of his Malay retainers. Relationships between the two men quickly deteriorated with Hare’s followers gradually leaving him and seeking protection from Ross. This eventually led to Hare finally abandoning the island in March 1831 and taking up residence in Batavia, where he later died. Ross then made several appeals to both British and Dutch authorities to annex the islands and for a short period in 1841, on orders from the Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies, the Dutch flag flew over them. This action was not supported by The Hague and the matter of Dutch ownership lapsed. Finally on a visit by HMS Juno on 31 March 1857 Captain Stephen Fremantle, RN annexed the islands as British territories.

Two brothers of John Clunies-Ross, Robert and James, followed in his footsteps becoming masters of merchantmen trading to the East and provided support to the early settlement. Robert did not remain but was the father of the eminent Australian veterinary scientist Sir Ian Clunies-Ross. James eventually settled on the Cocos Islands; taking command of the locally built schooner Harriet, he died on the islands in 1872.

Imperial Communications Network and Sydney/Emden

With the advent of cable communications a world-wide network that connected Britain with its Empire was established. Cable stations were scattered throughout the globe at such places as Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria, Aden, Colombo, Penang, Singapore and Hong Kong. A station linking Australia with this network was located on the Cocos Islands in 1901. To provide some support to this isolated outpost in 1910 the P&O liner Morea notified the cable station that she would pass close by and drop a barrel with fresh provisions and mail. Other P&O ships were to follow suit, and other than a break because of WW II, this service continued until 1954 when it was superseded by regular air services.

The cable station at Direction Island in South Keeling came to prominence during WW I when on 8 November 1914 the German cruiser SMS Emden landed a 43 strong detachment to destroy the cable station, under the command of Emden’s First Lieutenant Hellmuth von Mucke. This was largely a failure as the station had sufficient time to send a distress signal when a strange ship was sighted. This signal was intercepted by Allied troop transports and their escorts en route from Albany to Colombo with the outcome of the resultant battle between HMAS Sydney and SMS Emden being well known. As the landing party was interrupted damage to the cables was not severe and they were repairable with communications through Cocos only briefly interrupted. The now stranded landing party commandeered an island schooner Ayesha (the first name of Mrs George Clunies-Ross) and under cover of darkness made a remarkable escape, and six months later, via the Arabian Peninsula, eventually returned safely to Germany with the loss of only four men. The now Korvettenkapitan von Mucke became a national hero. On 13 November 1914 the armed merchant cruiser HMS Empress of Asia arrived at Cocos to convey Captain von Muller and the remaining Emden survivors to imprisonment in Singapore.

Emden beached herself on North Keeling where much of the readily salvageable material was removed in 1915, and in 1950 a salvage company removed most of the hull and shipped it to Japan for scrap. All that remains of the wreck are some pieces of machinery covered by about eight metres of water. An interesting artefact from this period is a refurbished 4.1 inch gun taken from Emden’s main armament, which is now on display at the RAN Heritage Centre at Garden Island.

Christmas Island and Phosphate Mining

Man has never lived on Christmas Island, nor would it be a pleasant residence, apart from the fact that there is no water. Rear Admiral Sir William Wharton-Hydrographer Royal Navy 1888.

Christmas Island of about 135 km2 is only 360 km south of Jakarta whereas the nearest point to the Australian mainland at Exmouth is 1,560 km distant. The island was named by Captain William Mynors of another East Indiaman Royal Mary who sailed past on Christmas Day in 1643. William Dampier in the ship Cygnet landed in March 1688 and found it uninhabited.

During the famous scientific expedition conducted by HMS Challenger from 1872 to 1876 the surgeon and naturalist Dr John Murray (later Sir John) carried out surveys of Christmas Island where he predicted rich deposits of phosphate. This led to two visits by Royal Naval vessels in 1887 where samples of minerals were secured. In June 1888 Captain William May, RN of HMS Imperieuse formally claimed the island for the Crown.

However George Clunies-Ross, proprietor of the Cocos Islands some 860 km to the south west, regarded Christmas Island as part of his domain as he had sent expeditions there to cut timber and catch birds and bring these back to the Cocos. Accordingly in November 1888 he sent a small party to establish a settlement to maintain his claim, and followed this up by a letter to the Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements in Singapore seeking a formal land grant. As John Murray also sought a mining lease over the island this caused difficulty for the colonial administration which was resolved in 1891 when Clunies-Ross and Murray were granted a joint 99 year lease over the island. With a growing demand for high quality phosphate to improve agricultural production, in 1897 the Christmas Island Phosphate Company Limited was formed, with shares being closely owned by the two families and their friends.

Indentured Chinese labour was recruited to mine the ore and in 1901 the company purchased its own steamer, the first of a series of vessels named Islander. By 1905 the population of predominantly male Chinese had increased to over 1,000. Phosphate production grew and by 1906 over 100,000 tons were exported annually. In that year the Japanese became customers and were soon taking half the output with Australia and New Zealand also important customers. The First World War crippled phosphate exports which did not fully recover for the next 20 years.

Tranquillity, Garrison, Mutiny and Invasion

Both islands lapsed into tranquillity during the inter-war period. Phosphate exports began to gradually improve, and prior to WW II annual production reached 240,000 tons with 90% going to the Japanese market. In 1939 the Australian and British Governments jointly arranged for a survey flight across the Indian Ocean seeking alternative routes in case of wartime emergencies. In June 1939 the accomplished Australian aviator Captain P.G. Taylor flying a chartered Guba (predecessor of the more glamorously named Catalina) flying-boat landed on the Cocos lagoon and recommended the site as a future base. Regular Catalina flights used Cocos as a stopover for trans-Indian Ocean flights during WW II. With the advance of Japanese forces through South East Asia and thence into the Dutch East Indies in the 1940s they were again of strategic interest, but it was not until 1945 that an Allied air base was established on the Cocos Islands.

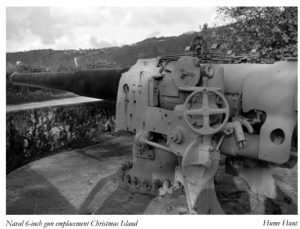

In November 1940 when engaged in convoy protection HMAS Perth was briefly diverted to Cocos to advise on protection measures for the cable station. The report made by Perth concluded that any action against the island would be brief as British naval forces could be readily called to assist, and recommended that a battery of two 6 inch guns would be adequate for the islands defence. This led to some ex WW I naval 6-inch guns being provided from Ceylon for defence, with a two gun battery on Cocos and a single gun battery on Christmas Island. Cocos was initially garrisoned in March 1941 by a detachment from the Ceylon Garrison Artillery based with their battery at Horsburgh Island, and a platoon of Ceylon Light Infantry based at the nearby Direction Island in defence of the cable station. In total the garrison comprised 75 officers and men. Christmas was more lightly garrisoned by 27 Indian soldiers under a subedar (lieutenant), who were ethnically Punjabi, of the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery; they were led by one officer and four NCOs who were all British. After the fall of Singapore in February 1942 the islands were administered from Ceylon.

The population of Christmas Island in 1941 had reached over 1,400, which included 32 Europeans. In December 1941 most of the European women and children were sent to Fremantle. Soon after the New Year, war came to these remote outposts when a submarine was sighted and fired upon by the naval gun at the recently constructed fort. A few weeks later on 21 January 1942 the Japanese submarine I-5 torpedoed and sank the Norwegian ship Eidsvold loading phosphate at Christmas Island. The crew were saved and taken to Singapore on the next voyage of the Islander. On 17 February 1942 Singapore surrendered to the Japanese and radio communication with the colonial administration was lost. This gave rise to a further evacuation of Europeans to Fremantle, which included John Paris, the CIP Company Chief Engineer, together with five Sikh policemen and their families. The Asian workforce had little choice but to remain as the Islander was not large enough to take them and Christmas Island was the only real home for many of them.

The most illuminating summary of this period is to be found in the official despatch to the Admiralty by the Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies, Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Arbuthnot, KCB, DSO, RN.

The Cocos Islands remained in our hands- rather to my surprise – forming a valuable communications link and halting place for aircraft on passage between Australia and Ceylon. Maintenance was of some complexity and I had on occasion to supply a warship to take stores for the garrison of Ceylon Garrison Artillery, the Cable Company’s staff, and the civil population. At the beginning of May a section of the garrison staged an armed mutiny which was suppressed. I provided HMIS Sutlej to take a relief party and bring back the mutineers for trial.

It should be remembered that Allied naval resources were sorely pressed during this period with Japanese naval forces entering that hitherto British preserve the Indian Ocean and pressing an attack upon Ceylon. The British Eastern Fleet had been removed from Singapore to Trincomalee, and with the advance of superior Japanese forces and fearing another Pearl Harbor; Admiral Sir James Somerville moved his fleet to the Maldives, out of range of air attack. When considered safe the cruisers HMA Ships Dorsetshire and Cornwall plus the older aircraft carrier HMS Hermes and her escorting destroyer HMAS Vampire were ordered to return to Ceylon. Their return was premature as all four ships were overwhelmed by Japanese aircraft and sunk off the Ceylon coast in early April 1942.

Another naval tragedy with significant loss of life began in the vicinity of Christmas Island on 27 February 1942. The elderly USN seaplane tender and its first aircraft carrier USS Langley together with the US cargo ship Sea Witch transporting vitally needed fighter aircraft from Australia to support Allied forces in Java were attacked and badly damaged by Japanese aircraft. Langley was abandoned and sunk by her escorting destroyers the US Ships Edsall and Whipple. Sea Witch made port and delivered her crated aircraft but shortly after these were destroyed when the port was abandoned. Survivors were taken to Christmas Island where they were transferred to the tanker USS Pecos. The US ships were again discovered by enemy aircraft causing them to proceed to sea. During the confusion one of the ex Langley officers, LCDR Thomas Donovan, USN possibly fortunately became stranded on the island and was to share the same fate as the other Europeans. In the ensuing battle Esdall and Pecos (now carrying 700 survivors) were sunk as was the Dutch merchantman Modjokerto. Coming to the rescue for a second time Whipple managed to save 231 survivors and return these to safety of Australian waters. The bombing raids on 28 February and 1 March to the island destroyed the radio station and an oil storage tank.

Next it was the turn of the Allied merchantman Nam Yong which was torpedoed 50 km off the island. The 36 survivors, including six Australian soldiers who had escaped from Singapore, made for Christmas Island. On 7 March, just as they were about to land, they found themselves in the midst of a bombardment by a Japanese naval group shelling the island whilst remaining out of range of the naval gun sited at Smith Point. With five killed and several injured this led the District Officer to hoist a white flag, but the Japanese steamed away without attempting to land. Captain Williams then replaced the offensive white flag with the Union flag.

Christmas Island Mutiny

There was unrest amongst some of the Indian troops who believed Japanese propaganda concerning the liberation of India from British rule. During the night of 10 March the havildars (sergeants) Mir Ali and Ghulam Qadir unlocked the armoury and distributed weapons and munitions amongst their supporters. Their subedar (lieutenant) Muzaffar Khan was unaware of the plot and was sleeping when awoken by gunshots around 2.30 am when the British officer and four NCOs were killed, with their bodies thrown into the sea. The troops then went back to the fort where they were joined by the Sikh policemen and watchmen. A total of 60 men of Indian origin were addressed by the subedar and it became clear that not all of them supported the mutiny. The remaining Europeans were rounded up and confined. Mir Ali wanted them killed but was persuaded against this course by Muzaffar Khan.

Soon after dawn on 31 March 1942 a Japanese squadron of three cruisers, eight destroyers, one oiler and two transports arrived off the island under the command of Rear Admiral Shoji Nishimura flying his flag in the cruiser IJNS Naka. This overwhelming force landed some 850 troops unopposed and occupied the island. The fleet had been shadowed by the US submarine Seawolf which fired torpedos at Naka but it was not until the next day with her final salvo that she hit her target. The cruiser was disabled and had to be towed to Singapore for repairs.

Christmas Island was now part of the South-East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere under the protection of the Emperor. This was the southernmost conquest by Japanese forces during WW II and would remain under their rule for the next three and a half years. Mir Ali welcomed the invaders on behalf of the Indian troops but to his astonishment found that the Indians were put to work as labourers. Most of the 21 Europeans with specialist skills were reallocated to their tasks to get the mining operations restarted, with the remainder also working as labourers.

Three days later the squadron departed, leaving behind a limited garrison. The main vessel involved in exporting small amounts of phosphate to Java was the coastal ship Nissei Maru. On 17 November 1942 when loading phosphate Nissei Maru was torpedoed and sunk by the US submarine Searaven with the loss of three Malay stevedores and two Japanese guards. This led to the abandonment of further attempts to export phosphate, with stocks being stockpiled and the departure of most of the Japanese garrison.

Cocos Island Mutiny

On 3 March 1942 a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft flew over the Cocos Islands and towards dusk a Japanese cruiser, two destroyers and a submarine closed the islands. The cruiser commenced a short bombardment of 20 rounds which lasted about 15 minutes causing explosions and fires. Surprisingly, as the Japanese ships were within range of the shore battery fire was not returned, with the decision taken only to resist a landing on the island. The manager of the Cable Station had the forethought to send a plain language message saying the island had been attacked and the cable station damaged beyond repair – this was far from the case as the cable station remained in service throughout the war. The ruse seemingly worked for inexplicably the Japanese did not land on the island to take possession and check upon the damage. Later that month the Ceylonese commanding officer of the garrison, Captain Wickramasuriya, was relieved by Captain George Gardiner, an Englishman who had worked in Ceylon, from where he had gained his commission. Following Captain Gardiner’s arrival morale deteriorated and there was a breakdown in discipline. Some of the young well educated soldiers were antagonistic towards the strict new regime and were influenced by radical elements encouraged by freely available Japanese propaganda emanating from Radio Manila and Tokyo Rose. The conditions were ripe for one of the most bizarre chapters in British military legal history.

After learning of a successful mutiny on Christmas Island, some 15 members of the Ceylon Garrison Artillery mutinied on the night of 8 May 1942. The aim was to arrest their officers and gain control of the gun battery which they could then train on the Ceylon Light Infantry on nearby Direction Island forcing them to surrender. A radio message would then be sent inviting Japanese forces to accept control of the Islands.

The mutiny was not well organised and was crushed by loyalist forces with one soldier killed and one officer and one soldier wounded, all from loyalist forces. Upon regaining control Captain Gardiner had all suspects placed under armed guard and instigated a Field General Court Martial, which could be constituted in emergency conditions under the Articles of War dating back to 1718. The court convened on Horsburgh Island on 12 May and comprised Gardiner as president and two other military officers, one of whom was a doctor with less than one year’s military service, and there was no defence advocate. Late on 16 May the president delivered the court’s verdict with seven men found guilty of all charges and sentenced to death with another four men guilty of lesser charges and sentenced to varying degrees of imprisonment. Four other men were found not guilty and released.

The decisions were passed to the Ceylon high command which was concerned at the political implications of executing Ceylonese volunteers for mutiny. The sentences were referred to the British Judge Advocate General in India who ruled on the legality of the court’s findings and found that the three ringleaders were guilty and should be sentenced to death and the remainder to imprisonment with some reductions to the imposed sentences.

The mutineers were taken from the Island to Colombo in HMIS Sutlej where they were imprisoned, and the three ringleaders hanged in August 1942. These are the only recorded executions for mutiny of British and Commonwealth forces during WW II. The Cocos Islands were then unhindered until 25 December 1942 when the Japanese submarine I-166 shelled the island causing little damage, followed up by a bombing raid by a single aircraft. A bomb landing on an ammunition dump caused a large explosion with four men injured.

On Christmas Island the majority of the remaining Japanese troops, plus Indian troops, police and watchmen from the original garrison, European prisoners and about 800 Asian workers were transported from the Island to the Javanese port of Surabaya on 14 December 1943 in the converted minelayer Nanyo Maru. There remained on the island a population of less than 500 with a small number of Japanese administrators and soldiers. In June 1944 most of the remainder of the Japanese departed leaving behind a sergeant and 14 men, and on 24 August these were withdrawn. From the remaining residents a local Vigilance Committee was formed, who were given small arms and ammunition.

With the tide turning against the Japanese, on 22 August 1944 the submarine HMS Spiteful while on passage from the Malacca Straits to Fremantle, using her 3 inch gun, bombarded the Christmas Island oil tanks. Fire was returned by the defenders, it is assumed using the ex Royal Naval 6 inch gun, in which the submarine suffered slight damage and retired.

End of Hostilities

Before the end of the war in 1945 two airstrips were constructed on the Cocos Islands. These were used by three bomber squadrons and escort fighter aircraft manned by RAF and Dutch airmen stationed there to conduct raids against retreating Japanese forces in South East Asia during the last few months of the war. These airstrips were reactivated in the 1950s and 1960s when used as a refuelling stop for civilian aircraft but the advent of longer range aircraft ended this requirement.

While the war against Japan officially ended on 2 September 1945 it took some time for the news to reach far-flung outposts of Empire. On 24 September 1945 Australian troops freed prisoners of war and civilian internees from camps at Macassar in the Celebes, they were then ferried in HMA Ships Barcoo and Inverell to the submarine depot ship HMS Maidstone which was waiting off shore. Maidstone then made passage to Fremantle where the ex-prisoners were disembarked. Amongst this number were the European civilian prisoners from Christmas Island, all of whom had survived their ordeal.

The frigate HMS Rother departed from Singapore on 13 October with orders to convey Major Van Der Gaast to re-occupy Christmas Island and to hoist the Union flag with due ceremony. Rother landed an armed party ashore on 18 October 1945, taking control to an enthusiastic welcome from the local Asian community. Having provided emergency supplies, Rother departed two days later to report on the state of affairs and left the island still under control of the Vigilance Committee.

After being requisitioned by the Australian Government as a supply vessel the Islander was released at the end of hostilities and arrived back at Flying Fish Cove on 21 December 1945 carrying John Paris, a medical officer and five supervisors. The Islander next made for Batavia to collect Captain Shaw, a British Army officer who was to take up duty as Military Administrator.

On 21 January 1946 two Indian Army officers and a Royal Engineers corporal arrived from Batavia to conduct an inquiry into the mutiny.

While retribution to those involved in the Cocos Island mutiny had been swift the mutineers from Christmas Island were scattered throughout the Netherlands East Indies. However they were pursued and eventually brought to account.

During 1947 and 1948 in Singapore eight mutineers from Christmas Island were tried, seven were found guilty and sentenced to death. While the ringleaders may have been guilty of mutiny and murder they were from the politically sensitive Punjab region and following representations from the newly independent governments of India and Pakistan their sentences were reduced to penal servitude for life. The chief ringleader Mir Ali was never found. The last of the prisoners was released in July 1957.

With the end of the war the Australian government recognised the strategic importance of these two islands and their potential for communication networks, civil aviation and phosphate deposits. Negotiations began with the British government, leading to the transfer of sovereignty of the Cocos Islands to the Commonwealth on 23 November 1955 and Christmas Island on 1 October 1958.

The first post-war exports of phosphates began in February 1946 but all was not well with a breakdown in labour relations, and in August it was necessary to send the naval depot ship HMS Derby Haven with a number of police to the island to restore order. By the next year there were gradual improvements with over 100,000 tons of ore exported. On 31 December 1948 the entire mining operations on Christmas Island was sold by the CIP Company for £2,690,000, to be managed by the British Phosphate Commission which was a consortium controlled by Australian and New Zealand government authorities.

of John Clunies-Ross

Recent history

Another twist of fate connecting these islands to our naval history relates to the Sydney/Kormoran battle of 19 November 1941. Nearly three months later, on 6 February 1942 a Carley float with a decomposed body clothed in the remains of a blue boiler suit was sighted off Christmas Island and towed ashore. The body which was buried was assumed to have been from a survivor of HMAS Sydney. In September 2006 the body was exhumed for DNA testing and in November 2008 re-buried at Geraldton War Cemetery. No DNA link has been established with any relatives of Sydney personnel.

With the end of WW II the Cocos gun battery on Horsburgh Island was partially removed and all that remains are rusting remnants, but the battery above Flying Fish Cove on Christmas Island remains to this day. In 1966 the cable station on Direction Island at Cocos was closed and now there is nothing to remind us of this important outpost. In 2010 the population of the Cocos Islands, now confined to only two islands, is about 600 persons, many of whom can trace their ancestry to the Hare and Ross times of over 185 years ago and fondly remember the feudal regime imposed by their ‘Tuan’. These islanders are mainly engaged in agriculture, fishing and tourism.

In 2010 Christmas Island had 1,500 permanent residents. Only 130 are now employed in mining and the Federal Government has recently announced the mines are expected to close within the next nine years. Attempts at a tourism industry have met with mixed results, with a casino and resort opened in 1993 closing within five years. However the end of conflict in one part of the world often produces unforeseen consequences in another such as the migration of peoples who are either displaced, liable to persecution or seeking improved economic outcomes. The end of the Vietnamese War and subsequent further conflict in the Asian region has produced an increase in people seeking asylum in places such as Australia. Being close to the Asian mainland the Cocos and Christmas Islands have become a frequent first port of call of so called illegal immigrants.

Boats carrying asylum seekers, most of whom journeyed via Indonesia, began arriving at Christmas Island in the late 1980s, in the beginning originating from Vietnam. A temporary immigration detention centre was established here in 2001. CDRE William (Bill) Taylor, RAN, Rtd was Administrator for the Indian Ocean Territories from 1999 to 2003 with the infamous ‘Tampa Affair’ of August 2001 occurring during his period of administration. A large permanent detention centre was constructed and opened in December 2008 to handle increasing numbers of refugees from Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan, and subsequently from Sri Lanka. In 2012 better resourced asylum seekers started arriving at the Cocos Island voyaging directly from Sri Lanka. The historic and strategic importance of these islands remains of concern to all members of our naval community.

Bibliography

Crusz, Noel, The Cocos Islands Mutiny, Fremantle Arts Centre Press, Fremantle, WA, 2001.

Gibson-Hill, C. A., The Colourful Early History of the Cocos-Keeling Islands, The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society – reprinted from its Journal for December 1952, Kuala Lumpur, 1953.

Hunt, John, Suffering Through Strength – The Men Who Made Christmas Island, Blue Star Print, Canberra, ACT, 2011.

Television documentary, Dynasties – The Clunies-Ross Family, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Sydney, 2004.